Anne Brontë, the sixth and final child of Patrick and Maria Brontë, was born not in Haworth but in Thornton – another moorside village of Bradford, around six miles distant. She was just three months old when her family moved to Haworth, the village that would become forever associated with the Brontë sisters, but the story of why they moved is a fascinating and surprising one in its own right.

Patrick was a clergyman in the Church of England from County Down in what is now Northern Ireland. He had enjoyed a number of assistant curateships before becoming vicar of Thornton, and he was delighted at first to find that the post gave him a parsonage to live in free of charge, the building which is now the wonderful Emily’s on Market Street. The Brontë family was growing, however, and Patrick soon wrote to his Bishop to say it was inadequate for him.

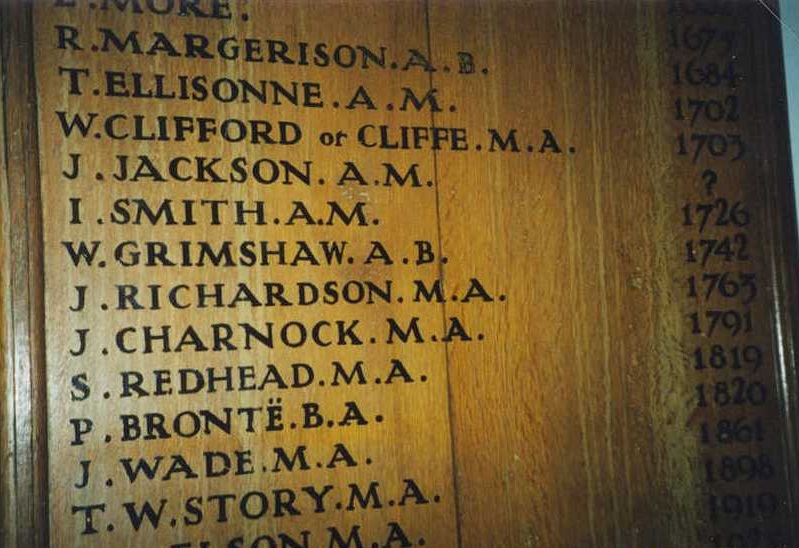

It was perhaps with this in mind that in mid-1819 the Vicar of Bradford offered him the opportunity to become Curate of Haworth after the death of its long time incumbent James Charnock. Haworth was a strange parish in many ways, as it was a sub-parish of Bradford meaning that the Vicar of Bradford, Henry Heap, received a percentage of the money it raised. Heap also thought that meant he had the right to select Haworth’s curate, but an ancient tradition stated that the parish elders were allowed to select their own priest. This caused a stand off reported in The Leeds Intelligencer newspaper in June 1819:

‘We hear that the Rev. P. Brontë, curate of Thornton, has been nominated by the vicar of Bradford, to the valuable perpetual curacy of Haworth, vacated by the death of the Rev. James Charnock; but that the inhabitants of the chapelry intend to resist the presentation, and have entered a caveat accordingly.’

Made aware of the strength of the villager’s complaint, Patrick informed Heap that he no longer wished to be considered for the post. The Vicar of Bradford then installed Reverend Samuel Redhead in the position; he had stood in for Reverend Charnock throughout his illness, so was surely a safe choice – in this belief, Reverend Heap was badly mistaken.

The Haworth elders were even more incensed that they had been snubbed twice and reacted furiously to Redhead’s appointment. There are two accounts of what happened next. Elizabeth Gaskell, in her brilliant biography of Charlotte Brontë, describes the Haworth villagers stamping on the church floor with their clogs until Redhead could not be heard at his first service. They later send a drunken chimney sweep on the back of a donkey to confront him, and then chase him out of the church with such threats of violence that he has to flee on horseback.

This sounds a wild account, but the actuality may have been even worse as there is one other account, and it comes from the Bishop of Ripon, a man who later became Archbishop of Canterbury. Bishop Charles Longley stayed at Haworth in March 1853. Patrick Bronte’s account of how he came to be curate of Haworth amazed him so much that he immediately wrote to his wife, and this letter is now part of the archives at Lambeth Palace. What he describes is nothing less than an attempt to murder their priest Samuel Redhead:

‘There is an ancient feud between Bradford and Haworth… the people of Haworth can by the trust deed of the living, prevent the person appointed by the vicar [of Bradford] from entering the Parsonage or receiving any of the emoluments, if he does not please them… in the case of Mr. Redhead, the inhabitants exercised their right of resistance and opposition and to such a point did they carry it, that they actually brought a Donkey into the church while Mr. Redhead was officiating and held up its head to stare him in the face – they then laid a plan to crush him to death in the vestry, by pushing a table against him as he was taking off his surplice and hanging it up, foiled in this for some reason or other they then turned out into the Churchyard where Mr. Redhead was going to perform a funeral and were determined to throw him into the grave and bury him alive.’

Following this there was no way that Redhead could officiate there again, so at last a compromise was reached. Henry Heap met the villagers who agreed to accept his original choice, Patrick Brontë, as long as they could officially nominate him rather than the vicar – keeping their old rights alive. This is how Anne Brontë came to travel, cradled in her mother’s arms, across the moors on April 20th 1820. It was an auspicious move, for although Haworth brought terrible tragedies to the Brontë family, with Maria Brontë dying just a year after her husband had taken up his new position, it also provided the stimulus and inspiration for a series of books that changed the literary world.