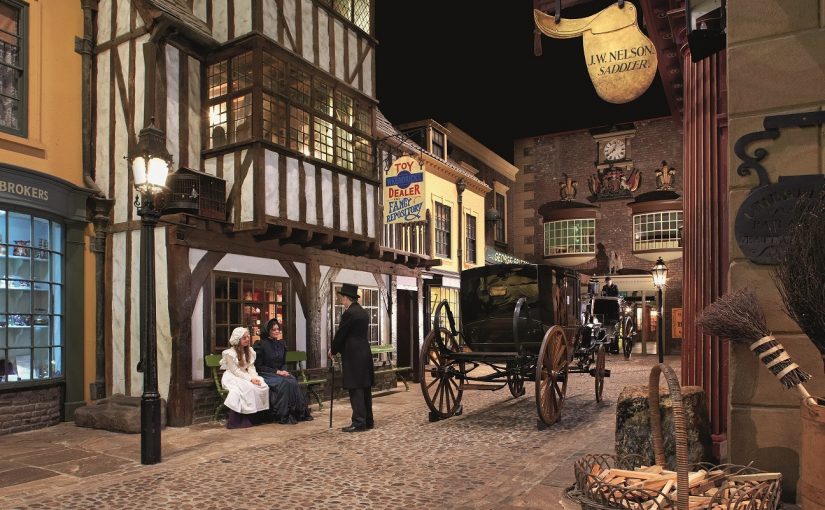

Today marks the two hundredth anniversary of the birth of the most remarkable writer who has ever drawn breath: Emily Jane Brontë. On 30th July 1818, in Thornton near Bradford, she became the fifth child to be born to Patrick and Maria Brontë, and Anne’s birth a year and a half later would complete the brilliant, if precarious, family unit.

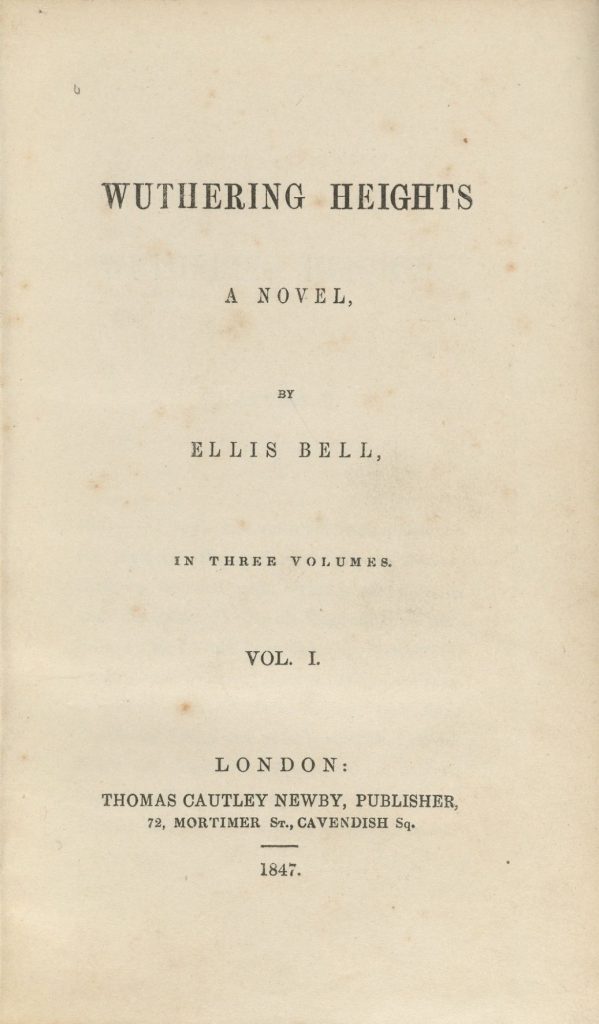

How should we celebrate this most special of days? We could re-read ‘Wuthering Heights‘, in my opinion the greatest book ever written. We could dip in and out of her poetry, the verse that she was so passionate about throughout her life. We can simply spend a reflective moment thinking of this daughter of Yorkshire, but as alluded to in last week’s post, one newspaper has decided to celebrate it in a very different way.

The Guardian’s attack upon Emily and the people who love her was as ludicrous as it was insulting, but it has been good to see people leap to her defence, such as in this post from the ever illuminating Brontë blogger Nicola Friar. On the 200th birthday of a woman who has brought to much love and happiness into my life, I must do the same.

There is a growing tendency among some people to disparage the United Kingdom’s achievements in the field of arts and culture. This little island has produced the likes of Shakespeare, Aphra Behn, Blake, Constable, Britten, Vaughan Williams, Zadie Smith, Wordsworth, Percy and Mary Shelley, Jane Austen, Burns and the Brontës; these towering figures and their incredible achievements are things we as a nation can be justly proud of, yet instead some delight in traducing their towering accomplishments in garish acts of self-promotion. We live in an age where Lilliputtians are ever seeking a new Gulliver to belittle, and this reached a nadir in last week’s Guardian’s article “The strange cult of Emily Brontë and the ‘hot mess’ of Wuthering Heights.”

As today marks the 200th anniversary of the birth of Emily Brontë, a woman still celebrated and loved across the world. It’s understandable, therefore, that the media is taking a fresh look at Emily and her legacy, but it is quite clear that the Guardian’s intent was not to praise Emily Brontë but to bury her. The choice of Kathryn Hughes to write the appraisal would surely seem perverse otherwise, for here is a woman who admits freely that she dislikes Emily Brontë and that she has never finished her only novel, the sublime ‘Wuthering Heights’. It is the equivalent of a restaurant critic reviewing a meal they have never tasted, or a sports correspondent reporting on the World Cup final after following it via a Twitter feed, but worse than this are the factual inaccuracies and strange conclusions that litter the article, and it’s this that has prompted me to respond in print.

I have loved Emily Brontë’s writing since I discovered ‘Wuthering Heights’ atop the reading list I’d been given in my first week at University. I was blown away by the book’s power and urgency, and a life long love affair with the Brontës and all their works had me in a vice like grip. I was happy to be held there, and in subsequent years my admiration for Emily, Charlotte and Anne has only grown, which is why my latest biography, ‘Emily Brontë – A Life In 20 Poems,’ was a sheer pleasure to research and write.

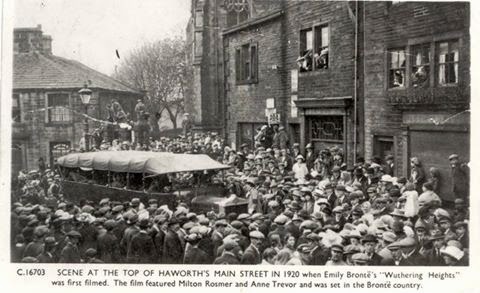

It was somewhat surprising therefore to read the Guardian’s assertion that ‘nearly all Emily Brontë’s biographers and scholars over the past century have been women.’ This is to discount seminal works by the likes of Edward Chitham, but worse than this it seems that the writer is using the championing of Emily by women writers to belittle her achievements, rather than seeing this as a cause for celebration. Visitors to Haworth are also sure to notice that women and men equally are drawn to the three literary sisters, so the Guardian’s claims seem either dispiriting or disingenuous.

Hughes then attempts to prove that Emily Brontë is not a great writer by virtue of the fact that acclaimed 20th century literary critic F.R. Leavis failed to include Emily in his book ‘The Great Tradition’. Nothing could be further from the truth, however, than to say that Leavis did not rate Emily Brontë as a first class writer. On the contrary, he asserted that: “There is, too, Emily Brontë, who has hardly yet had full justice as a poet; I will record, without offering it as a checked and deliberate critical judgement, that her ‘Cold in the earth’ is the finest poem in the nineteenth-century part of the Oxford Book of English Verse.”

This poem, beginning ‘Cold in the earth – and the deep snow piled above thee,’ is better known by its title ‘Remembrance,’ and it is indeed a colossal feat of poetic composition. Hughes seems not only to have failed to finish ‘Wuthering Heights’ (which in itself is some achievement, as the book is not overly long and rattles along at a furious pace), but to be unaware of Emily’s outstanding verse output. Emily Brontë is without doubt one of the finest Victorian poets, and it is this poetry that led directly to the series of seven Brontë novels we love today.

Charlotte Brontë wrote of discovering a book of Emily’s poems in the autumn of 1845 and being stunned at finding them, “condensed and terse, vigorous and genuine. To my ear, they also had a peculiar music – wild, melancholy, and elevating.”

This discovery led, after initial protestations from the reserved Emily, to the first Brontë book to reach print: ‘Poems by Currer, Ellis and Acton Bell’, and from there it was a short hop to the Brontë’s first prose works.

We can see from this recollection that Charlotte thought incredibly highly of Emily, and indeed of Anne too, and writing after their deaths she concluded that, “I may sum up all by saying, that for strangers they were nothing, for superficial observers less than nothing; but for those who had known them all their lives in the intimacy of close relationship, they were genuinely good and truly great.”

As Charlotte knew better than anybody, the genius of Emily in print was very different to the shy Emily of Haworth, but this aspect of Emily’s character is cruelly twisted by Hughes. As her experience at Roe Head school demonstrates, Emily could suffer severe anxiety when in strange company, and yet this condition (so serious that Charlotte worried it would lead to Emily’s death when at school) is openly mocked within the article. Emily is berated for staying at home, as if she had chosen this out of laziness, when as both Charlotte and Anne acknowledged she was actually working harder than either of them in overseeing domestic duties at the parsonage. This task had previously been the domain of loyal servant Tabby Aykroyd, but she was by then in her dotage and less than mobile after a leg injury. By taking on the majority of her tasks, Emily allowed Tabby to stay in the house she loved, and to retain her dignity. This was typical of the kind hearted Emily, rather than demonstrating a ‘self-interested’ streak as Hughes attests.

Perhaps unsurprisingly the Guardian also choose to attach to Emily an epithet that they deem the worst insult of all – Tory. There is no indication, however, that Emily had any political inclinations whatsoever, and she certainly never made pronouncements on them or referred to them in her prose or poems.

There is no ‘cult’ of Emily Brontë as the writer sneeringly suggests, there is simply a vast number of people on every continent who appreciate Emily Brontë for what she was: a writer of brilliance whose novel and poetry still has the power to shock, to entertain, to cheer. We should not let this article detract from Emily’s 200th birthday celebrations. Charlotte once said of her sister that despite mixing little in Haworth society, she knew them. When we read ‘Wuthering Heights’, with its depictions of love, lust, betrayal, romance, passion and revenge, we realise too that she knows us. Kathryn Hughes does not seem to know the novel she has failed to finish, nor the writer behind it, so let us turn instead to the words of a woman who did. Ellen Nussey was the lifelong close friend of Charlotte Brontë, and a frequent visitor to Haworth Parsonage, and yet, in a letter to Elizabeth Gaskell, she had no hesitation in naming a woman who impressed her even more than Charlotte:

“I have at this time before me the history of a mighty and passionate soul, whom every adventure that makes for the sorrow or gladness of man would seem to have passed by with averted head. It is of Emily Brontë I speak, than whom the first 50 years of this century produced no woman of greater or more incontestable genius.”

Emily Brontë deserves more than clickbait headlines and tiresome, shouty articles as she celebrates her two hundredth anniversary; she deserves our thanks and praise, she deserves to be read and understood. On this day let us simply say thank you, Emily Brontë – you were a brilliant wordsmith, a brilliant mind, a brilliant woman. Happy 200th birthday!