For Brontë fans today is a day which brings mixed emotions. It is Easter Sunday, a day of joy and one that would have been especially beloved of the religious Brontë family. Today, also, however, marks one of the very saddest Brontë anniversaries. The Brontë novels and lives show what we all know, that life brings its challenges but it also brings its joys and triumphs. On this special day let us choose to look at the joyous side of life by looking at proposals in the Brontë works.

Agnes Grey

Whilst all Brontë novels possess some level of autobiography, I believe it is Agnes Grey by Anne Brontë which draws most from its author’s life, and from her dreams of what her life could have been. I also believe, as regular blog readers will know (and please do hit that ‘subscribe’ button if you haven’t already done so), that Anne Brontë was in love with her father’s assistant curate William Weightman.

Alas, Weightman caught cholera after visiting a sick parishioner and died far too young. Anne Brontë was denied her dreams of a proposal, a marriage and a loving life to follow, but she determined to give herself that happy ending in her debut novel. It is quite clear to me that Agnes is Anne, and Reverend Weston is Reverend Weightman, which makes the following understated proposal scene even more touching:

‘“I went to get ready, and was down again in a few minutes; though, of course, I took a little more pains with my attire than if I had merely been going out on some shopping expedition alone. The thunder-shower had certainly had a most beneficial effect upon the weather, and the evening was most delightful. Mr. Weston would have me to take his arm; he said little during our passage through the crowded streets, but walked very fast, and appeared grave and abstracted. I wondered what was the matter, and felt an indefinite dread that something unpleasant was on his mind; and vague surmises, concerning what it might be, troubled me not a little, and made me grave and silent enough. But these fantasies vanished upon reaching the quiet outskirts of the town; for as soon as we came within sight of the venerable old church, and the – hill, with the deep blue beyond it, I found my companion was cheerful enough.

“I’m afraid I’ve been walking too fast for you, Agnes,” said he: “in my impatience to be rid of the town, I forgot to consult your convenience; but now we’ll walk as slowly as you please. I see, by those light clouds in the west, there will be a brilliant sunset, and we shall be in time to witness its effect upon the sea, at the most moderate rate of progression.”

When we had got about half-way up the hill, we fell into silence again; which, as usual, he was the first to break.

“My house is desolate yet, Miss Grey,” he smilingly observed, “and I am acquainted now with all the ladies in my parish, and several in this town too; and many others I know by sight and by report; but not one of them will suit me for a companion; in fact, there is only one person in the world that will: and that is yourself; and I want to know your decision?”

“Are you in earnest, Mr. Weston?”

“In earnest! How could you think I should jest on such a subject?”

He laid his hand on mine, that rested on his arm: he must have felt it tremble – but it was no great matter now.

“I hope I have not been too precipitate,” he said, in a serious tone. “You must have known that it was not my way to flatter and talk soft nonsense, or even to speak the admiration that I felt; and that a single word or glance of mine meant more than the honied phrases and fervent protestations of most other men.”

I said something about not liking to leave my mother, and doing nothing without her consent.

“I settled everything with Mrs. Grey, while you were putting on your bonnet,” replied he. “She said I might have her consent, if I could obtain yours; and I asked her, in case I should be so happy, to come and live with us – for I was sure you would like it better. But she refused, saying she could now afford to employ an assistant, and would continue the school till she could purchase an annuity sufficient to maintain her in comfortable lodgings; and, meantime, she would spend her vacations alternately with us and your sister, and should be quite contented if you were happy. And so now I have overruled your objections on her account. Have you any other?”

“No – none.”

“You love me then?” said he, fervently pressing my hand.

“Yes.”’

Jane Eyre

We have just witnessed a simple, and simply beautiful, proposal scene. The proposal scene which follows from Jane Eyre by Charlotte Brontë was rather more complicated. Not merely because (spoiler alert) Rochester is already married (a fact which Jane doesn’t know at this point) but because of the class difference between the protagonists – Jane believes that Rochester is going to marry the wealthy Blanche Ingram and she is therefore planning to leave his service, but Rochester has other plans:

‘“Pity!” he said, and sighed and paused. “It is always the way of events in this life,” he continued presently: “no sooner have you got settled in a pleasant resting-place, than a voice calls out to you to rise and move on, for the hour of repose is expired.”

“Must I move on, sir?” I asked. “Must I leave Thornfield?”

“I believe you must, Jane. I am sorry, Janet, but I believe indeed you must.”

This was a blow: but I did not let it prostrate me.

“Well, sir, I shall be ready when the order to march comes.”

“It is come now – I must give it to-night.”

“Then you are going to be married, sir?”

“Ex-act-ly – pre-cise-ly: with your usual acuteness, you have hit the nail straight on the head.”

“Soon, sir?”

“Very soon, my – that is, Miss Eyre: and you’ll remember, Jane, the first time I, or Rumour, plainly intimated to you that it was my intention to put my old bachelor’s neck into the sacred noose, to enter into the holy estate of matrimony – to take Miss Ingram to my bosom, in short (she’s an extensive armful: but that’s not to the point – one can’t have too much of such a very excellent thing as my beautiful Blanche): well, as I was saying – listen to me, Jane! You’re not turning your head to look after more moths, are you? That was only a lady-clock, child, ‘flying away home.’ I wish to remind you that it was you who first said to me, with that discretion I respect in you – with that foresight, prudence, and humility which befit your responsible and dependent position – that in case I married Miss Ingram, both you and little Adèle had better trot forthwith. I pass over the sort of slur conveyed in this suggestion on the character of my beloved; indeed, when you are far away, Janet, I’ll try to forget it: I shall notice only its wisdom; which is such that I have made it my law of action. Adèle must go to school; and you, Miss Eyre, must get a new situation.”

“Yes, sir, I will advertise immediately: and meantime, I suppose – ” I was going to say, “I suppose I may stay here, till I find another shelter to betake myself to:” but I stopped, feeling it would not do to risk a long sentence, for my voice was not quite under command.

“In about a month I hope to be a bridegroom,” continued Mr. Rochester; “and in the interim, I shall myself look out for employment and an asylum for you.”

“Thank you, sir; I am sorry to give – ”

“Oh, no need to apologise! I consider that when a dependent does her duty as well as you have done yours, she has a sort of claim upon her employer for any little assistance he can conveniently render her; indeed I have already, through my future mother-in-law, heard of a place that I think will suit: it is to undertake the education of the five daughters of Mrs. Dionysius O’Gall of Bitternutt Lodge, Connaught, Ireland. You’ll like Ireland, I think: they’re such warm-hearted people there, they say.”

“It’s a long way off, sir.”

“No matter – a girl of your sense will not object to the voyage or the distance.”

“Not the voyage, but the distance: and then the sea is a barrier – ”

“From what, Jane?”

“From England and from Thornfield: and – ”

“Well?”

“From you, sir.”

I said this almost involuntarily, and, with as little sanction of free will, my tears gushed out. I did not cry so as to be heard, however; I avoided sobbing. The thought of Mrs. O’Gall and Bitternutt Lodge struck cold to my heart; and colder the thought of all the brine and foam, destined, as it seemed, to rush between me and the master at whose side I now walked, and coldest the remembrance of the wider ocean – wealth, caste, custom intervened between me and what I naturally and inevitably loved.

“It is a long way,” I again said.

“It is, to be sure; and when you get to Bitternutt Lodge, Connaught, Ireland, I shall never see you again, Jane: that’s morally certain. I never go over to Ireland, not having myself much of a fancy for the country. We have been good friends, Jane; have we not?”

“Yes, sir.”

“And when friends are on the eve of separation, they like to spend the little time that remains to them close to each other. Come! we’ll talk over the voyage and the parting quietly half-an-hour or so, while the stars enter into their shining life up in heaven yonder: here is the chestnut tree: here is the bench at its old roots. Come, we will sit there in peace to-night, though we should never more be destined to sit there together.” He seated me and himself.

“It is a long way to Ireland, Janet, and I am sorry to send my little friend on such weary travels: but if I can’t do better, how is it to be helped? Are you anything akin to me, do you think, Jane?”

I could risk no sort of answer by this time: my heart was still.

“Because,” he said, “I sometimes have a queer feeling with regard to you – especially when you are near me, as now: it is as if I had a string somewhere under my left ribs, tightly and inextricably knotted to a similar string situated in the corresponding quarter of your little frame. And if that boisterous Channel, and two hundred miles or so of land come broad between us, I am afraid that cord of communion will be snapt; and then I’ve a nervous notion I should take to bleeding inwardly. As for you, – you’d forget me.”

“That I never should, sir: you know – ” Impossible to proceed.

“Jane, do you hear that nightingale singing in the wood? Listen!”

In listening, I sobbed convulsively; for I could repress what I endured no longer; I was obliged to yield, and I was shaken from head to foot with acute distress. When I did speak, it was only to express an impetuous wish that I had never been born, or never come to Thornfield.

“Because you are sorry to leave it?”

The vehemence of emotion, stirred by grief and love within me, was claiming mastery, and struggling for full sway, and asserting a right to predominate, to overcome, to live, rise, and reign at last: yes, – and to speak.

“I grieve to leave Thornfield: I love Thornfield: – I love it, because I have lived in it a full and delightful life, – momentarily at least. I have not been trampled on. I have not been petrified. I have not been buried with inferior minds, and excluded from every glimpse of communion with what is bright and energetic and high. I have talked, face to face, with what I reverence, with what I delight in, – with an original, a vigorous, an expanded mind. I have known you, Mr. Rochester; and it strikes me with terror and anguish to feel I absolutely must be torn from you for ever. I see the necessity of departure; and it is like looking on the necessity of death.”

“Where do you see the necessity?” he asked suddenly.

“Where? You, sir, have placed it before me.”

“In what shape?”

“In the shape of Miss Ingram; a noble and beautiful woman, – your bride.”

“My bride! What bride? I have no bride!”

“But you will have.”

“Yes; – I will! – I will!” He set his teeth.

“Then I must go: – you have said it yourself.”

“No: you must stay! I swear it – and the oath shall be kept.”

“I tell you I must go!” I retorted, roused to something like passion. “Do you think I can stay to become nothing to you? Do you think I am an automaton? – a machine without feelings? and can bear to have my morsel of bread snatched from my lips, and my drop of living water dashed from my cup? Do you think, because I am poor, obscure, plain, and little, I am soulless and heartless? You think wrong! – I have as much soul as you, – and full as much heart! And if God had gifted me with some beauty and much wealth, I should have made it as hard for you to leave me, as it is now for me to leave you. I am not talking to you now through the medium of custom, conventionalities, nor even of mortal flesh; – it is my spirit that addresses your spirit; just as if both had passed through the grave, and we stood at God’s feet, equal, – as we are!”

“As we are!” repeated Mr. Rochester – “so,” he added, enclosing me in his arms, gathering me to his breast, pressing his lips on my lips: “so, Jane!”

“Yes, so, sir,” I rejoined: “and yet not so; for you are a married man – or as good as a married man, and wed to one inferior to you – to one with whom you have no sympathy – whom I do not believe you truly love; for I have seen and heard you sneer at her. I would scorn such a union: therefore I am better than you – let me go!”

“Where, Jane? To Ireland?”

“Yes – to Ireland. I have spoken my mind, and can go anywhere now.”

“Jane, be still; don’t struggle so, like a wild frantic bird that is rending its own plumage in its desperation.”

“I am no bird; and no net ensnares me; I am a free human being with an independent will, which I now exert to leave you.”

Another effort set me at liberty, and I stood erect before him.

“And your will shall decide your destiny,” he said: “I offer you my hand, my heart, and a share of all my possessions.”

“You play a farce, which I merely laugh at.”

“I ask you to pass through life at my side – to be my second self, and best earthly companion.”

“For that fate you have already made your choice, and must abide by it.”

“Jane, be still a few moments: you are over-excited: I will be still too.”

A waft of wind came sweeping down the laurel-walk, and trembled through the boughs of the chestnut: it wandered away – away – to an indefinite distance – it died. The nightingale’s song was then the only voice of the hour: in listening to it, I again wept. Mr. Rochester sat quiet, looking at me gently and seriously. Some time passed before he spoke; he at last said –

“Come to my side, Jane, and let us explain and understand one another.”

“I will never again come to your side: I am torn away now, and cannot return.”

“But, Jane, I summon you as my wife: it is you only I intend to marry.”

I was silent: I thought he mocked me.

“Come, Jane – come hither.”

“Your bride stands between us.”

He rose, and with a stride reached me.

“My bride is here,” he said, again drawing me to him, “because my equal is here, and my likeness. Jane, will you marry me?”’

It is worth remembering when we read this that Charlotte Brontë, as she explicitly stated in a letter, saw Rochester as a romantic hero who had been wronged by fate, and whose intentions were honourable. This is such a powerful scene, and I think it was portrayed brilliantly in the 1983 tv adaptation starring Timothy Dalton and Zelah Clarke:

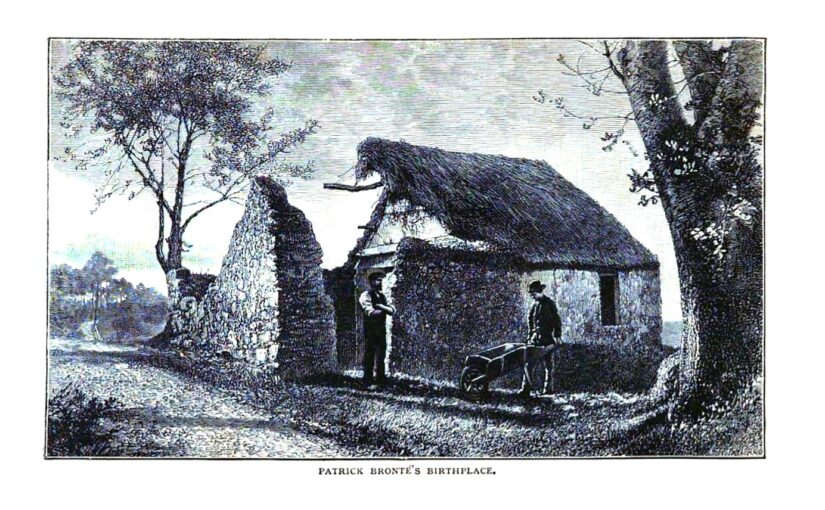

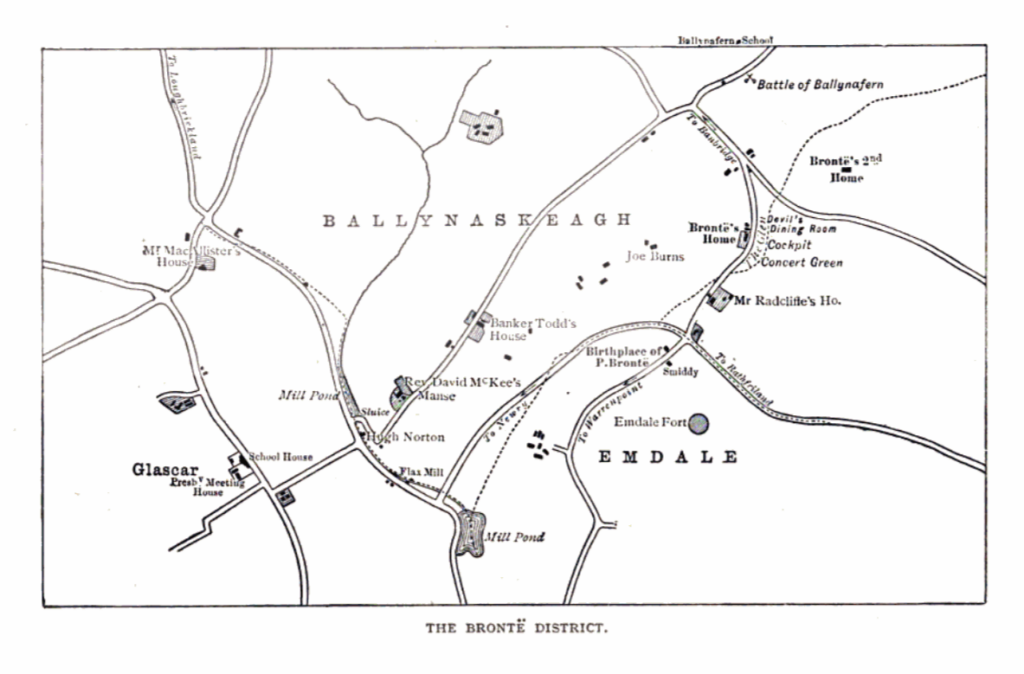

Charlotte Brontë eventually had her own real-life proposal scene, but at first she turned Arthur Bell Nicholls down. Their romance grew, however, and they eventually married and found great happiness. It was an all too brief happiness, for on this day 1855 Charlotte Brontë died in the cruellest of circumstances: when she was pregnant.

The Easter story is one of hope triumphing over devastating loss, the hope of eternal life, of eternal love. In a very real way Charlotte Brontë still lives today, for as long as this Earth spins people will read her books, know her name, and love her.

I had a proposal scene of my own this week. I’ve been on holiday in Lapland with the love of my life, and I’m thrilled to say that she has agreed to become my wife. I’m over the moon with happiness, so may I wish you all a very Happy Easter and I hope you can join me here at the earlier time of next Friday, the 5th of April, for some more good Brontë news!