I always like to provide something new in my blogs looking at Anne Brontë and her remarkable family, but there are some events that we simply have to return to an annual basis. Today is one such day, for in today’s post we are looking at the sad death of Anne Brontë – which occurred exactly 174 years ago today.

Anne, as you may well know, is the only Brontë sibling not buried below the flooring of Haworth church – although she is mentioned in the memorials there. On May 24th Anne Brontë set off from Haworth, with sister Charlotte Brontë and friend Ellen Nussey beside her. Their destination: Scarborough, a resort Anne knew and loved from her time as governess to the Robinson family, and one that was reputed to have healing waters in its spa. Anne, of course, knew there was no prospect of a cure after being diagnosed with terminal consumption (tuberculosis) but she clung to a hope that she could regain some of her health and live a little longer. Alas, it was a forlorn hope.

On the 24th they arrived at their overnight stop of York, staying at the George Hotel on Coney Street – what is left of the hotel now houses a Waterstones bookshop. Whilst in York Anne also bought ribbons and bonnets, ready for the fashionable resort of Scarborough, and visited the huge and imposing York Minster – another site familiar to her from her five years with the Robinsons of Thorp Green Hall, not far from York.

On the 25th, they arrived in Scarborough and Anne bought a season ticket for the spa and the newly opened Cliff Bridge leading to it. From Charlotte’s records, we know that they also enjoyed cups of dandelion coffee.

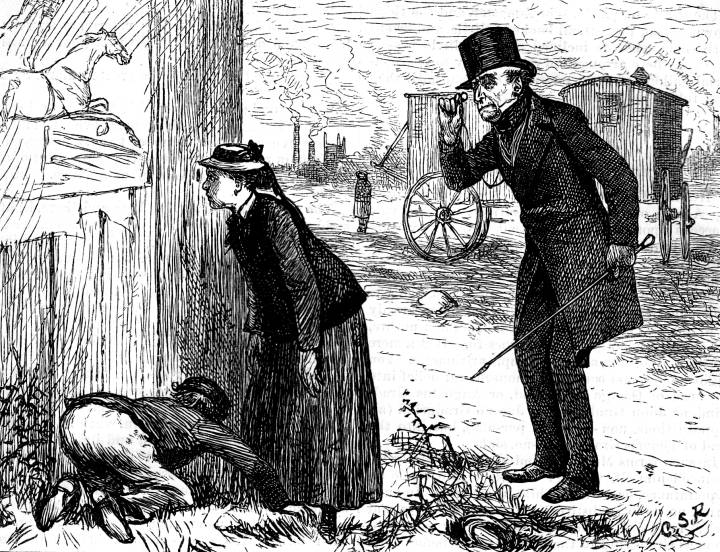

On the 26th of May, Anne took the waters of the spa on her own, but she collapses on her way back to her lodgings and has to be carried inside by the housekeeper. The end is rapidly approaching. In the afternoon, however, Anne drives a donkey cart along the beach on her own, having eschewed the services of the usual driver in case he mistreated the donkey. Donkeys are still a feature of Scarborough’s south beach today.

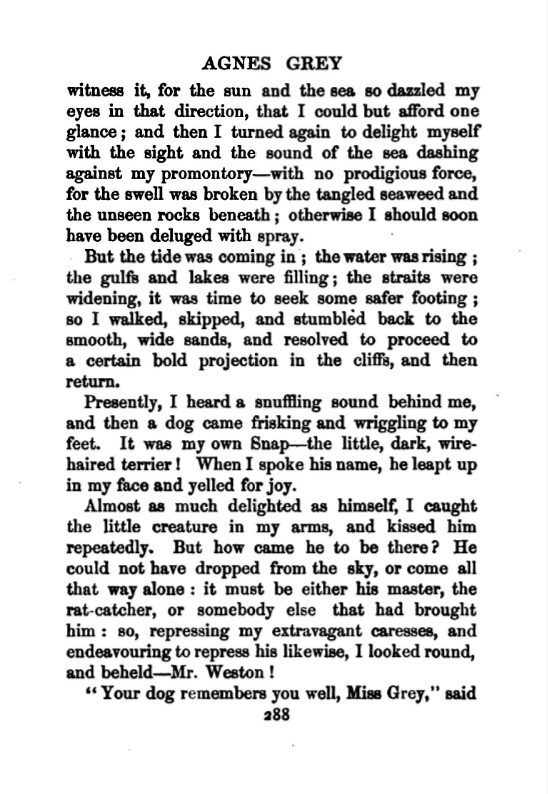

The next day, the 27th, sees Anne head back to the beach, and she asks Charlotte and Ellen to wait on a bench as she walks on alone. Perhaps Anne’s mind was drawn back to a scene she had set on that very same beach in Agnes Grey just three years earlier. In the scene Agnes is reunited with Weston, and of course they themselves are clearly modelled on Anne and her lost love William Weightman.

Anne is now in no doubt that her end is near, and she asks Charlotte whether they should return to Haworth. It’s too late, and both sisters knew that it would be too painful for their father to bury another child so soon after the deaths of Branwell and Emily Brontë. Anne spent her final night in Wood’s Lodgings looking out of the window at the sea, at the horizon she loved. Ellen Nussey later movingly described this as Anne’s glorious sunset:

“It [the night of the 27th May] closed with the most glorious sunset ever witnessed. The castle on the cliff stood in proud glory gilded by the rays of the declining sun. The distant ships glittered like burnished gold; the little boats near the beach heaved on the ebbing tide, inviting occupants. The view was grand beyond description. Anne was drawn in her easy chair to the window to enjoy the scene with us. Her face became illuminated almost as much as the glorious sun she gazed upon. Little was said, for it was plain that her thoughts were driven by the imposing view before her to penetrate forwards to the region of unfading glory.”

We know, in fact, that this was not an actual physical sunset they witnessed, for the sun sets over Scarborough’s North Bay, not the South Bay where they lived. A sentence in a letter that Meta Gaskell sent to Ellen Nussey after the death of her mother Elizabeth Gaskell, however, provides the key to understanding Ellen’s description:

“When we had all come in we had tea, and then were sitting around the fire in the drawing-room, so cozily and happily, when quite suddenly, without a moment’s warning, in the middle of a sentence, she fell forwards – dead… I cannot tell you how beautiful a “sunset” it was, though we did not know it was that at the time; all mama’s last days had been full of loving thought and tender help for others.”

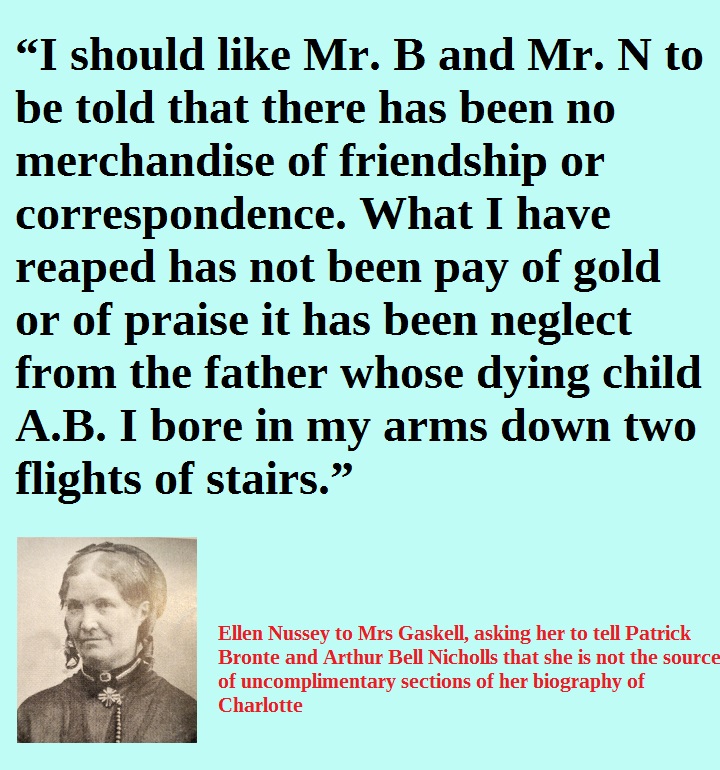

In asking about the death of Elizabeth Gaskell, Ellen has referred to it as a ‘sunset’ – this then is the phrase Ellen uses to describe the last hours of a person’s life. On the morning of the 28th Anne is too weak to walk down the stairs, but Ellen carries her down. On the way they bump heads and Ellen apologises instantly, but Anne tells her she has nothing to apologise for. Anne is then placed in a chair looking out to sea again. This act of kindness by Ellen Nussey, so typical of her, is at the heart of a painful letter she later sent to Elizabeth Gaskell after the publication of her biography of Charlotte Brontë. It seems that both Patrick Brontë and Arthur Bell-Nicholls (who had a long running, and mutual, enmity towards Ellen) thought that she was the source of unflattering comments within the biography. They were wrong, and a distressed Ellen wrote:

Anne clearly had little time left to live, a doctor was called for but said he could do nothing and return later. Anne continued to look out of the window, absorbed in her thoughts. Once again we turn to Ellen for a full and moving account of Anne’s last moments:

“She still occupied her easy chair, looking so serene, so reliant: there was no opening for grief as yet, though all knew the separation was at hand. She clasped her hands, and reverently invoked a blessing from on high ; first upon her sister, then upon her friend, to whom she said, ‘Be a sister in my stead. Give Charlotte as much of your company as you can.’ She then thanked each for her kindness and attention. Ere long the restlessness of approaching death appeared, and she was borne to the sofa ; on being asked if she were easier, she looked gratefully at her questioner, and said, ‘It is not you who can give me ease, but soon all will be well through the merits of our Redeemer.’ Shortly after this, seeing that her sister could hardly restrain her grief, she said, ‘Take courage, Charlotte; take courage.’ Her faith never failed, and her eye never dimmed till about two o’clock, when she calmly and without a sigh passed from the temporal to the eternal. So still, and so hallowed were her last hours and moments. There was no thought of assistance or of dread. The doctor came and went two or three times. The hostess knew that death was near, yet so little was the house disturbed by the presence of the dying, and the sorrow of those so nearly bereaved, that dinner was announced as ready, through the half-opened door, as the living sister was closing the eyes of the dead one.”

This is a very sad day for fans of Anne Brontë, but we must all take courage. Anne was not scared of death, she had unwavering faith at the moment she needed it most. What she could not have known is that she would still be remembered, still be loved, nearly two centuries later. Keep Anne Brontë, and the sister and friend she left behind, in your thoughts at 2pm today. I hope to see you next week for another new Brontë blog post.