Jane Eyre is one of the most celebrated works of literature of all time, but there is much more to its creator than this incredible novel of a governess, a mysterious attic and an unquenchable passion. Its author was a complex woman, sometimes fiery, sometimes dismissive, but always full of an enormous love for those she was close to. It’s these qualities that we remember as we say ‘Happy 202nd birthday, Charlotte Brontë!’

Charlotte Brontë was born on 21st April in the parsonage on Market Street in Thornton, a moor-side village four miles from Bradford. Already at Thornton were Charlotte’s elder siblings Maria and Elizabeth, and in the four years after Charlotte’s birth she would be joined by her brother Branwell and then her younger sisters Emily and Anne.

Charlotte Brontë was named after Charlotte Branwell, the youngest sister of her mother Maria. As this Charlotte lived in Penzance with her husband, and cousin, Joseph Branwell, the two namesakes never saw each other, but we know that the Brontë and Branwell families corresponded over the 400 miles that separated them.

By spring 1820, just three months after Anne’s birth, the family were making a short trip to their new parish, and new home, of Haworth. Just a year after their arrival, Charlotte’s mother Maria tragically died and this terrible event would, in a way, lead to the literary treasures we have today. The siblings were thrown together, they developed an independence, but also a dread of people from outside their family unit. Their mother’s sister Elizabeth, known as Aunt Branwell, now lived with them in Haworth and made incredible sacrifices, financially and emotionally, but in those first months and years after their mother’s death it was eldest sister Maria who became a real and much loved mother figure, despite being of tender years herself.

We should never underestimate the devastation that the early losses of her mother and then eldest sisters had on Charlotte, and this is the root of the depressive bilious attacks that she often suffered from throughout her life. Her incredible spirit could not be bowed forever, however, and her brilliant novels are testimony to her fortitude and strength, as well as her genius. Her husband famously described Charlotte’s letters as ‘dangerous as lucifer matches’, and she certainly didn’t hold back in them. By examining them today we can still get a glimpse of the real Charlotte Brontë:

Teaching her sisters

‘In the morning from nine o’clock till half past twelve I instruct my sisters & draw, then we walk till dinner, after dinner I sew till tea-time, and after tea I either read, write, do a little fancy-work or draw, as I please. Thus in one delightful, though somewhat monotonous course my life is passed.’ (21 July 1832)

Self-criticism and love for Ellen Nussey:

‘What am I compared to you? I feel my own utter worthlessness when I make the comparison. I’m a very coarse common-place wretch! Ellen I have some qualities that make me very miserable, some feelings that you can have no participation in – that very few people in the world can at all understand… they burst out sometimes and then those who see the explosion despise me and I hate myself for days afterwards. We are going to have prayers, so I can write no more of this trash yet it is too true.’

(October 1836)

Life as a governess:

‘My dearest Lavinia [Emily Brontë]… I see now more clearly than I have ever done before that a private governess has no existence, is not considered as a living rational being except as connected with the wearisome duties she has to fulfil. While she is teaching the children, working for them, amusing them, it is all right. If she steals a moment for herself it is a nuisance.’

(8 June 1839)

Wish to move on in the world:

‘If I could leave home Ellen I should not be at Haworth now – I know life is passing away and I am doing nothing – earning nothing – a very bitter knowledge it is at moments, but I see no way out of the mist.’

(14 October 1846)

On the reception of ‘Jane Eyre’:

‘I feel honoured in being approved by Mr. Thackeray because I approve of Mr. Thackeray… one good word from such a man is worth pages of praise from ordinary judges. You are right in having faith in the reality of Helen Burns’ character: she was real enough: I have exaggerated nothing there: I abstained from recording much that I remembered respecting her, lest the narrative should sound incredible. Knowing this, I could not but smile at the quiet, self-complacent dogmatism with which one of the journals lays it down that “such creations as Helen Burns are very beautiful but very untrue”’.

(28 October 1847)

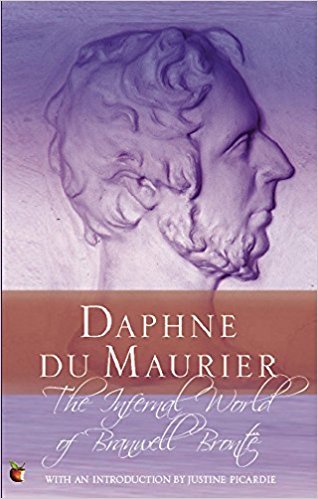

Mourning her siblings:

‘They [Emily and Anne] are both gone, and so is poor Branwell – and Papa has now me only – the weakest, puniest, least promising of his six children. Consumption has taken the whole five… I am ordered to remain at the sea-side a while… I do not know what my next address will be, I shall wander a week or two on the east coast and only stop at quiet, lonely places.’

(4 June 1849)

Finding love with her husband:

‘I trust I feel thankful to God for having enabled me to make what seems a right choice – and I pray to be enabled to repay as I ought the affectionate devotion of a truthful, honourable, unboastful man… We go to Kilkee a watering-place on the South-West coast. The letters may be addressed – Mrs. Arthur Nicholls.’

(10 July 1854)

We will leave her letters there, and leave Charlotte in a moment of love and happiness that she richly deserved. She endured a lot, yet always fought on, and it was she that was the driving force behind the brilliant novels of the Brontë sisters that we love today. Let’s raise a toast and a smile and say ‘Happy Birthday, Charlotte Brontë’.