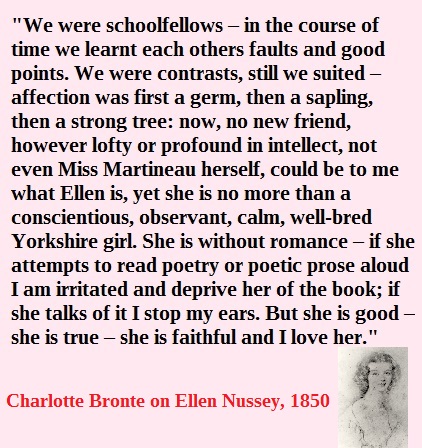

This week has marked a sad anniversary in the Brontë story (there seem to be so many of those, but remember there’s a corresponding happy anniversary for each one) as Ellen Nussey passed away on the 26th November 1897. Ellen was the great friend of Charlotte Brontë, and Ellen paid this glowing tribute to the qualities which mattered to her most:

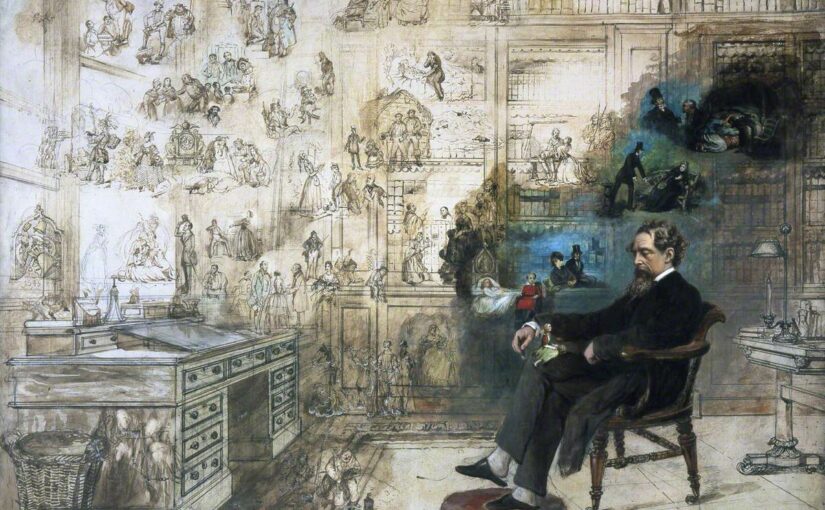

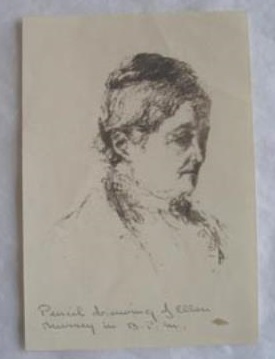

In today’s new post we’re going to look at Ellen Nussey’s death, but we’re going to lighten the mood with some glorious pictures of Ellen too. Let’s begin with a picture of Ellen Nussey that Charlotte herself drew in their youth:

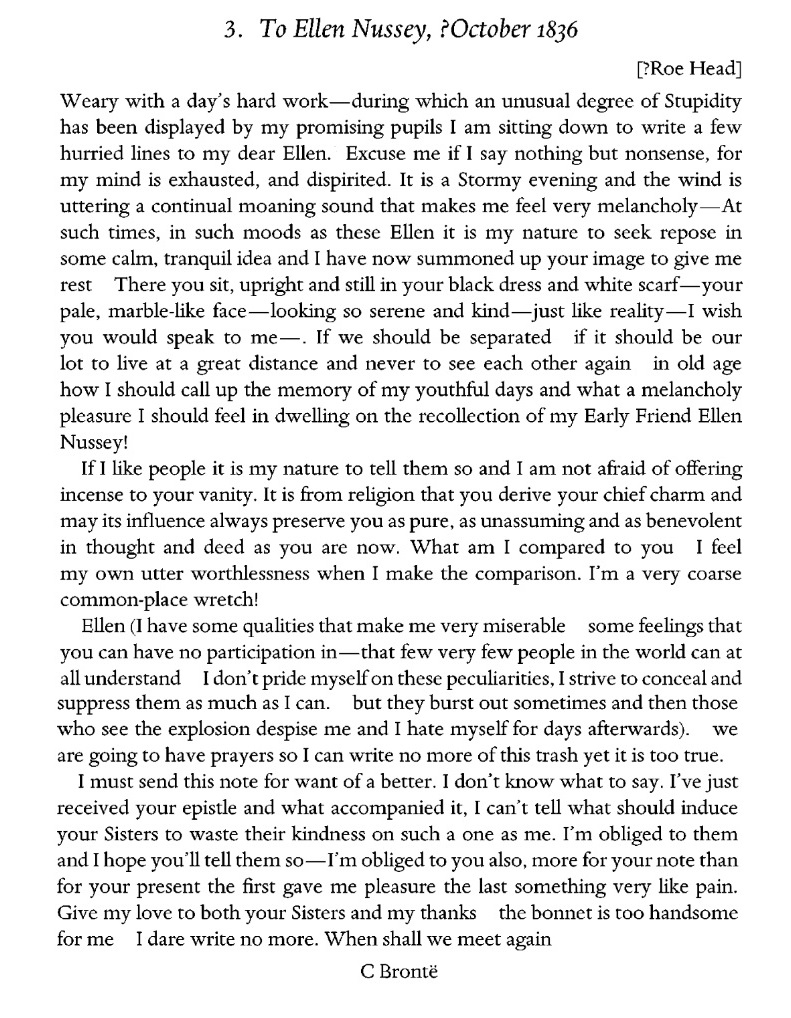

Charlotte Brontë and Ellen Nussey first met at Roe Head School, Mirfield in January 1831, and Ellen later recalled their first meeting:

‘Turning to the window to observe the look-out I became aware for the first that I was not alone; there was a silent, weeping, dark little figure in the large bay window; she must, I thought, have risen from the floor. As soon as I had recovered from my surprise, I went from the far end of the room, where the book-shelves were, the contents of which I must have contemplated with a little awe in anticipation of coming studies. A crimson cloth covered the long table down the centre of the room, which helped, no doubt, to hide the shrinking little figure from my view. I was touched and troubled at once to see her so sad and tearful.

I said shrinking, because her attitude, when I saw her, was that of one who wished to hide both herself and her grief. She did not shrink, however, when spoken to, but in very few words confessed she was “home-sick”. After a little of such comfort as could be offered, it was suggested to her that there was a possibility of her too having to comfort the speaker by and by for the same cause. A faint quivering smile lighted her face; the tear-drops fell; we silently took each other’s hands, and at once we felt that genuine sympathy which always consoles, even though it be unexpressed. We did not talk or stir till we heard the approaching footsteps of other pupils coming in from their play.”

A firm friendship was made, and a lasting one. Ellen it was who served as Charlotte’s chief bridesmaid and it was also Ellen, alongside Charlotte, who accompanied Anne Brontë on her final journey to Scarborough; even the reserved Emily Brontë took Ellen as a friend, a friendship that Ellen repaid by later remembering Emily as the greatest genius of the first half of the nineteenth century.

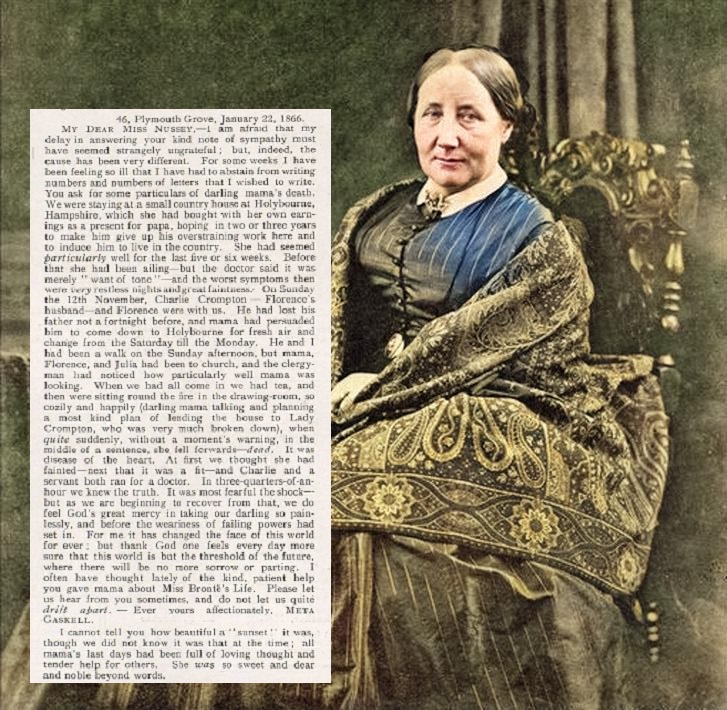

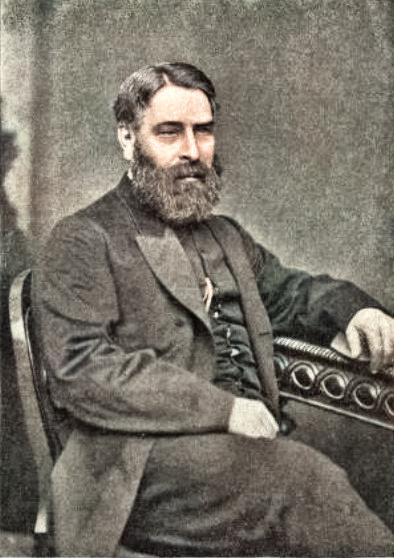

Ellen Nussey lived to be eighty years old. She never married; her one true, unending relationship was with the Brontës who had long predeceased her. It is thanks to her ripe old age (for the time) that we have so many photographs of Ellen, and a portrait of her. Ellen loved to talk about the Brontës, and she was never short of people willing to listen. There was a regular stream of visitors, Brontë fans, to her homes in Birstall and Gomersal in her later life, and one of these was the American-English artist Frederic Yates. He painted this beautiful portrait of Ellen in later years:

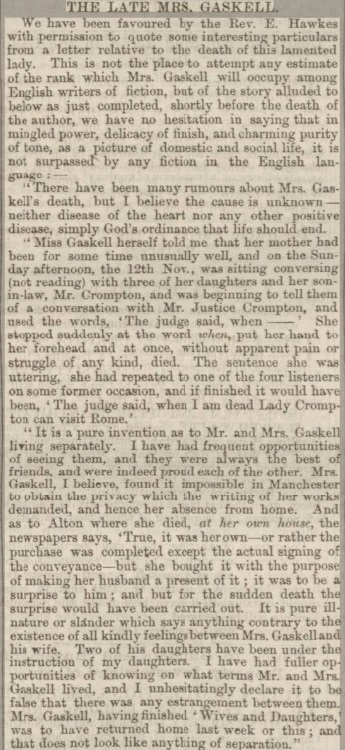

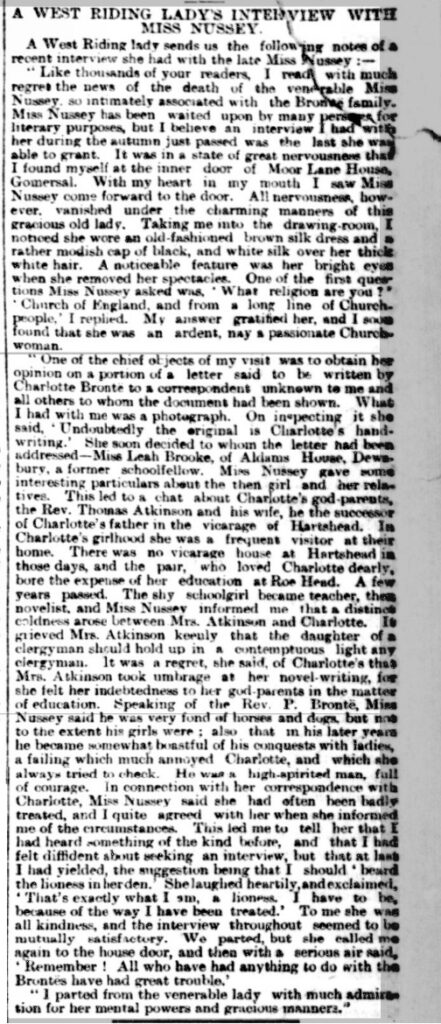

We have a record of perhaps the last visit to Ellen Nussey, and a fascinating one it is too. It appeared in the Yorkshire Post on 29th November 1897:

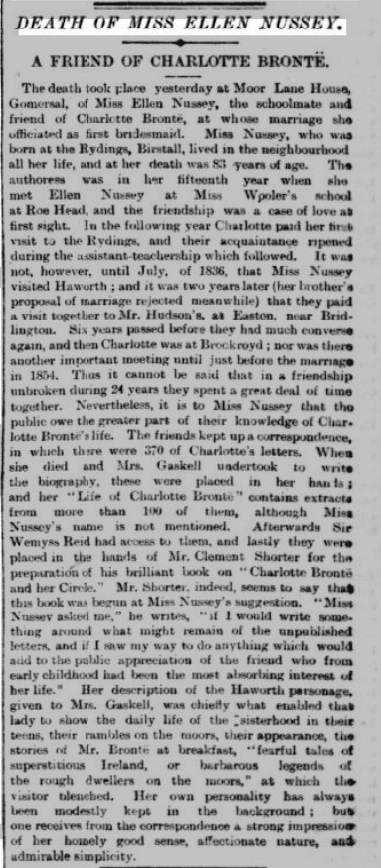

This same Yorkshire Post, two days earlier, had carried news of Ellen’s death:

Two days later, alongside the report of the visit by the unnamed West Riding lady, we hear a report of Ellen’s final moments:

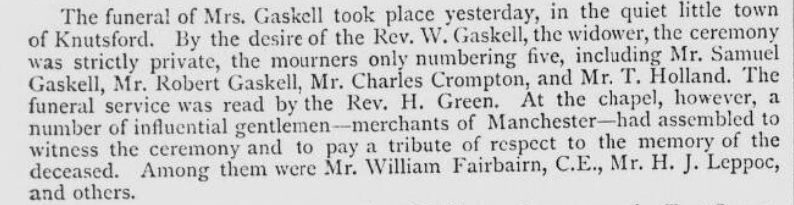

Ellen’s funeral took place on the 30th November 1897. We hear that the Brontë Society sent a wreath, but that her funeral was sparsely attended due to terrible weather. She lies now in St. Peter’s churchyard, Birstall (that’s it at the head of this post), not far from another woman who was central to the Brontë story: Margaret Wooler.

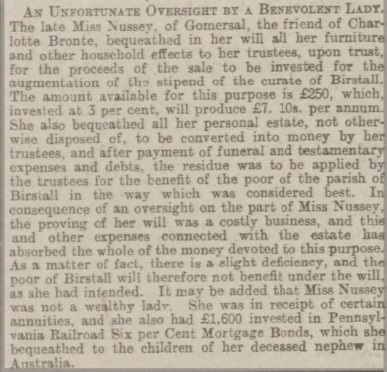

There’s a further sad incident to reflect upon, I’m afraid, that came two years after Ellen’s death. Ellen had a great love for the church, and she was always ready to help the church, its clergy, and wider society in general. She was generous both with her time and money, and in her will she had made provision for ‘the benefit of the poor of Birstall.’ Alas, as this report in the Manchester Evening News of 21st April 1899 reveals, legal wrangling and complications ate up all the money that Ellen left, and the poor and needy were left with nothing:

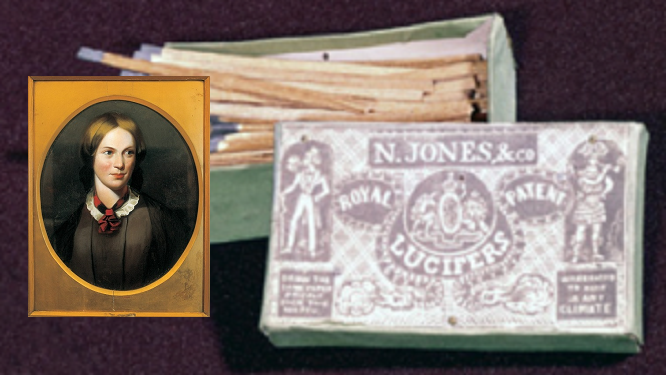

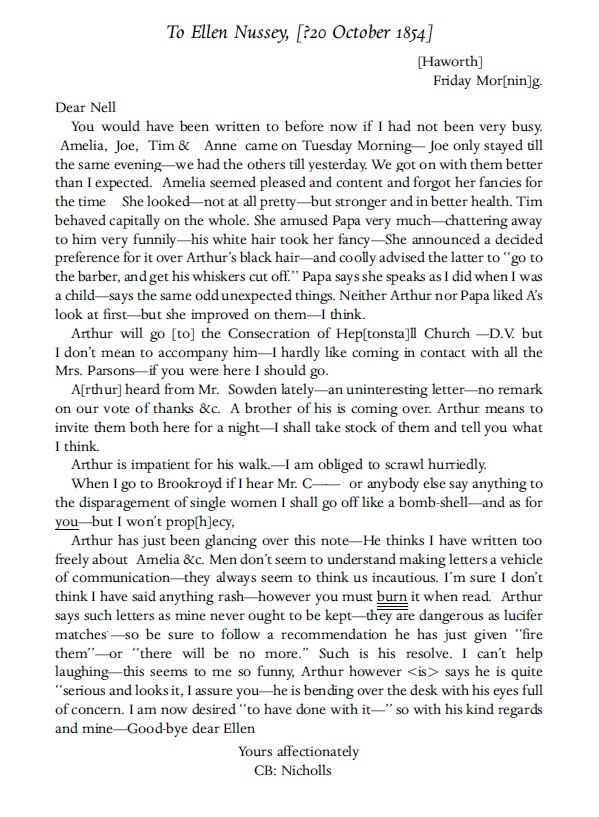

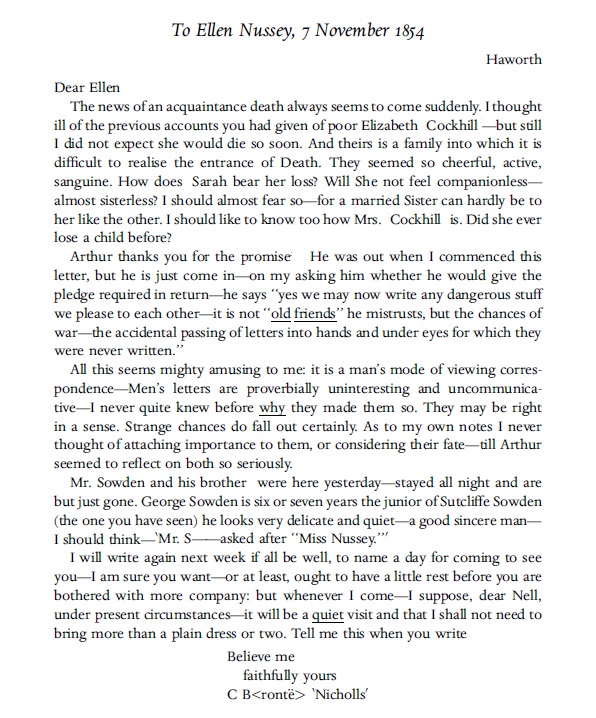

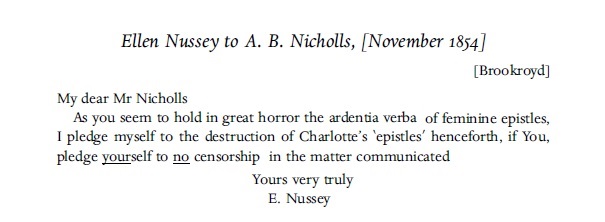

Nevertheless Ellen was remembered fondly by all who knew her and by those in the area as a whole. Today she is known to a wider world of Brontë lovers as the woman who preserved the Brontë legacy in the decades after their passing. It is thanks to the hundreds of Charlotte Brontë’s letters which Ellen kept that we know so much about the Brontës today. That’s a legacy that can never be diminished.

Charlotte loved Ellen dearly. It was to Ellen that she wrote frankly, ‘It is from religion that you derive your chief charm and may its influence always preserve you as pure, as unassuming and as benevolent in thought and deed as you are now. What am I compared to you? I feel my own utter worthlessness when I make the comparison.’ Now that’s a tribute! I hope to see you all again next week for another new Brontë blog post.

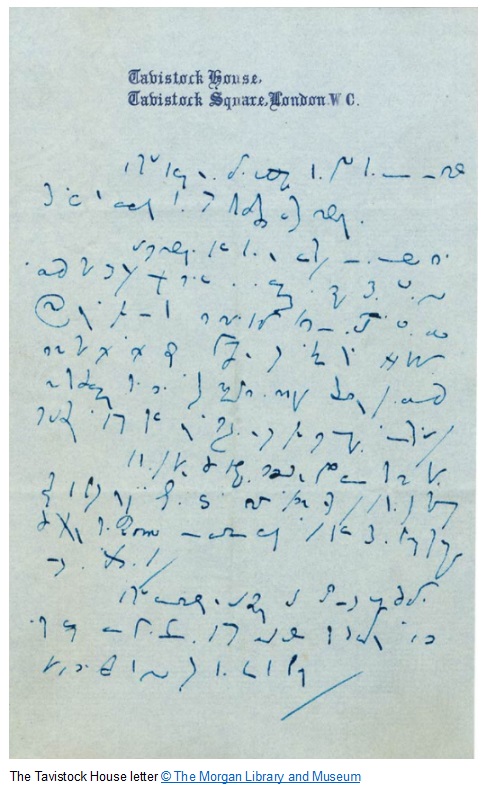

Oh, before I go, there’s another picture I want you to look at that you won’t have seen before. This late Victorian photograph was found in a West Yorkshire antique shop – to me it bears more than a resemblance to earlier photographs of Ellen Nussey, although this is of an older woman. Could this be the very last photograph of Ellen Nussey? It hangs proudly now on my wall.