When Charlotte and Anne Brontë arrived in London on the morning of 8th July 1848, they had just one thing on their mind: restoring their honour. A day earlier a letter had arrived from Charlotte’s publisher, Smith, Elder & Co. that would change literary history for ever. In it, George Smith asked if Currer Bell could explain how a book entitled The Tenant Of Wildfell Hall was being hawked to an American publisher as a new work by the author of Jane Eyre.

The truth of the matter, of course, was that The Tenant Of Wildfell Hall was written by Anne Bronte under the pseudonym of Acton Bell. The sisters’ use of male pseudonyms had been intended to hide the real identities of this shy trio and to ensure that their books were not judged unfairly because of the gender of the authors. As the events of July showed, however, it had been causing confusion and speculation. Anne’s unscrupulous publisher, Thomas Cautley Newby, had used this uncertainty to try to gain a better deal for Anne’s new book in the United States. This swiftly resulted in the letter which devastated Charlotte, Anne, and Emily.

One thing they couldn’t countenance was having their honesty questioned, but how could they solve this problem? At this point even their publishers had no idea of the true identity of the authors, but the sisters quickly agreed that this had to change. Emily, the most insular of all the Brontës, would not make the journey, but she gave her blessing to her two sisters as long as they still kept the identity of Ellis Bell a secret.

After checking in at the Chapter Coffee House on Paternoster Row, a location Charlotte had earlier stayed in en route to Brussels, they wasted little time in setting out for Smith, Elder & Co. Here they encountered another problem. The publisher was located at 65 Cornhill, a street running off from the Bank of England premises, and home to many bookshops and publishers. The sisters had a vague idea that it was not far from Paternoster Row but after setting out on foot got completely lost, and were too shy to ask for directions.

Charlotte recorded, when relaying the story of her London adventure to her friend Mary Taylor, that it took them well over an hour to finally reach the publisher. I recently retraced their steps and it took me ten minutes of gentle strolling to reach 65 Cornhill. In effect it’s a straight road which leads from Paternoster Row, past St Paul’s Cathedral, and then turning into Cheapside which in turn changes its name to Cornhill. Many of the buildings still there today would have been seen by the sisters, and Anne would have loved the stately imposing architecture unlike any she’d seen before.

Eventually the reached the building today. The Shanghai Commercial Bank stands on the spot today, but the original building is no more. Anne and Charlotte must have taken a moment on the threshold to compose themselves, could they actually carry out their plan, could they throw their masks of anonymity aside? Holding hands for comfort they stepped inside.

The ground floor was a bookshop. Charlotte walked to an assistant and asked to be taken to George Smith, the head of the publishing house. Unworldly as they were, it had not occurred to them that he might not be at work on what was a Saturday morning. Luckily for them, Smith was a workaholic and in his office on the floor above. The assistant, unaccustomed to such requests, nevertheless went to Smith’s office to pass on the request. He was unhappy at being disturbed and told the assistant to find out their names and their business. The assistant returned shortly to say that the women would not give him their names but said that it was important business and they must see him.

Smith was now intrigued, and asked for them to be shown up. He was surprised to see two women standing before him, they were small in stature, timid, and wearing clothes that were far from fashionable. He took a moment to survey them and then asked them why they wanted to see him.

At this point Charlotte stepped forward and planted the letter on his desk that she had received just a day earlier. It was addressed to Currer Bell.

Smith was now on the verge of becoming alarmed, he was not adverse to publishing mysteries but didn’t necessarily want to be in one himself.

‘Where did you get this?’, he asked Charlotte.

‘From the post office’, she replied, ‘it’s addressed to me.’ There was no going back now.

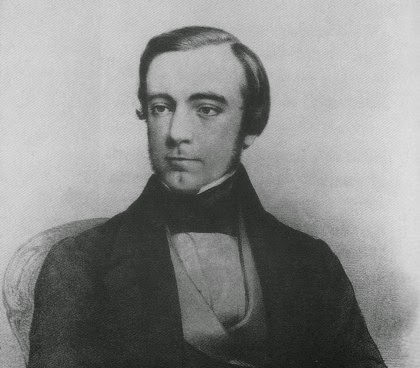

Smith, a young man who had recently taken over the firm from his father, could hardly take in what was happening. Could this really be his stellar new writer Currer Bell with whom he had exchanged so many letters? He produced paper and a pen, and asked Charlotte to sign her signature. Her ‘Currer Bell’, of course, matched those that Smith already had.

Smith was amazed, but there was another surprise to come. Charlotte explained that she was a poor clergyman’s daughter from Yorkshire by the name of Brontë, and then introduced her sister Anne and explained that she was Acton Bell who had recently caused so much controversy with The Tenant Of Wildfell Hall.

The mystery was now cleared up, and any charge of deception was quickly transferred from the sisters themselves to the publisher Newby. Smith left the office briefly and came back with his head reader, William Smith Williams. It was Williams who had first recognised the brilliance of Jane Eyre, and he too was now amazed to discover who Currer Bell really was. The sisters explained that they were now going to visit Thomas Newby and then return to Haworth, but Smith would hear nothing of it. They were now his guests of honour, and he would show them the respect their genius deserved. In next week’s blog you’ll read more about their prolonged stay in London, and how a joyous few days for Anne would lead directly to one of the most tragic events in English literature.

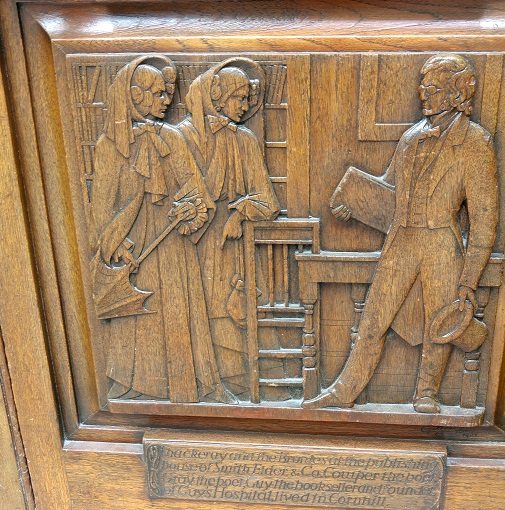

Cornhill hasn’t forgotten its two famous visitors. A wooden door stands at 32 Cornhill which is an incredible work of art by sculptor Walter Gilbert. Made in 1939 it’s one of London’s hidden treasures. The door features eight elaborate panels showing significant moments in Cornhill’s history. The first panel notes its founding by King Lucius in 179AD, and the eight panel shows two women talking to a man in a top hat: it is Charlotte and Anne Brontë at the moment of their ultimate triumph, and is at the head of this post.

Thank you for drawing my attention to Nick Holland’s Biography. Anne has been overshadowed by her sisters for too long!

Thank you so much Molly! I completely agree, and I hope you like my biography of Anne!