If you’ve followed this blog for a while, thank you, you may remember a post from a few years ago that included a petition to stop Kirklees council closing the historic Red House in Gomersal, West Yorkshire. Unfortunately, whilst there was huge public support for the Red House, the council decided to close it anyway, and it’s remained unused, but not unloved, ever since.

The good news is that an enthusiastic group of people are determined that the Red House should re-open. The aim is for the council to lease the building to this community group, after which it could become an important building for Brontë and history buffs and the wider community alike. Its potential really is huge, this historically important building could be a public museum again but it could also be an arts and retreat venue, a place for literary talks and festivals, a wedding venue, as well as a perfectly beautiful host for a wide variety of community groups and events.

Stage one is to convince Kirklees council to let this group address them and present their plans for a Red House revival. Once again, there’s a petition. Please take just a moment to click this link to the petition and sign it. It only takes a moment, but do remember to also click the email you’ll receive to confirm your signature.

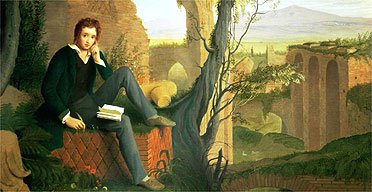

There are many reasons that the Red House is important, many of which can be found in this excellent article by Dr. Stephen Caunce which featured recently in the Huddersfield Examiner. As you’d expect, in today’s blog I’m going to concentrate on just why it’s so important to Brontë lovers. The Red House in Gomersal was for many years the home of Mary Taylor, one of a great trio of friends alongside Charlotte Brontë and Ellen Nussey. They met at Roe Head school at Mirfield, just four miles from Gomersal, the school where Anne Brontë later excelled as a pupil.

Charlotte grew very close to Mary Taylor, and to her younger sister Martha, and as well as Mary’s visits to Haworth Parsonage, Charlotte visited them at the Red House. So important was the house to Charlotte that she gave it a central role in her second published novel ‘Shirley’, where it can clearly be identified as Briarmains. Here in the book is Charlotte’s moving introduction to Briarmains and the Yorke family, for which we can read the Red House and the Taylors.

“But if Briar Chapel seemed alive, so also did Briarmains, though certainly the mansion appeared to enjoy a quieter phase of existence than the temple. Some of its windows too were aglow; the lower casements opened upon the lawn; curtains concealed the interior, and partly obscured the ray of the candles which lit it, but they did not entirely muffle the sound of voice and laughter. We are privileged to enter that front door, and to penetrate to the domestic sanctum.

It is not the presence of company which makes Mr. Yorke’s habitation lively, for there is none within it save his own family, and they are assembled in that farthest room to the right, the back parlour.This is the usual sitting-room of an evening. Those windows would be seen by daylight to be of brilliantly-stained glass, purple and amber the predominant hues, glittering round a gravely-tinted medallion in the centre of each, representing the suave head of William Shakespeare, and the serene one of John Milton. Some Canadian views hung on the walls—green forest and blue water scenery—and in the midst of them blazes a night-eruption of Vesuvius; very ardently it glows, contrasted with the cool foam and azure of cataracts, and the dusky depths of woods.

The fire illuminating this room, reader, is such as, if you be a southern, you do not often see burning on the hearth of a private apartment. It is a clear, hot coal fire, heaped high in the ample chimney. Mr. Yorke will have such fires even in warm summer weather. He sits beside it with a book in his hand, a little round stand at his elbow supporting a candle; but he is not reading—he is watching his children. Opposite to him sits his lady—a personage whom I might describe minutely, but I feel no vocation to the task. I see her, though, very plainly before me—a large woman of the gravest aspect, care on her front and on her shoulders, but not overwhelming, inevitable care, rather the sort of voluntary, exemplary cloud and burden people ever carry who deem it their duty to be gloomy. Ah, well-a-day! Mrs. Yorke had that notion, and grave as Saturn she was, morning, noon, and, night; and hard things she thought if any unhappy wight—especially of the female sex—who dared in her presence to show the light of a gay heart on a sunny countenance. In her estimation, to be mirthful was to be profane, to be cheerful was to be frivolous. She drew no distinctions. Yet she was a very good wife, a very careful mother, looked after her children unceasingly, was sincerely attached to her husband; only the worst of it was, if she could have had her will, she would not have permitted him to have any friend in the world beside herself. All his relations were insupportable to her, and she kept them at arm’s length.

Mr. Yorke and she agreed perfectly well, yet he was naturally a social, hospitable man, an advocate for family unity; and in his youth, as has been said, he liked none but lively, cheerful women. Why he chose her, how they contrived to suit each other, is a problem puzzling enough, but which might soon be solved if one had time to go into the analysis of the case. Suffice it here to say that Yorke had a shadowy side as well as a sunny side to his character, and that his shadowy side found sympathy and affinity in the whole of his wife’s uniformly overcast nature. For the rest, she was a strong-minded woman; never said a weak or a trite thing; took stern, democratic views of society, and rather cynical ones of human nature; considered herself perfect and safe, and the rest of the world all wrong. Her main fault was a brooding, eternal, immitigable suspicion of all men, things, creeds, and parties; this suspicion was a mist before her eyes, a false guide in her path, wherever she looked, wherever she turned.

It may be supposed that the children of such a pair were not likely to turn out quite ordinary, commonplace beings; and they were not. You see six of them, reader. The youngest is a baby on the mother’s knee. It is all her own yet, and that one she has not yet begun to doubt, suspect, condemn; it derives its sustenance from her, it hangs on her, it clings to her, it loves her above everything else in the world. She is sure of that, because, as it lives by her, it cannot be otherwise, therefore she loves it.

The two next are girls, Rose and Jessy; they are both now at their father’s knee; they seldom go near their mother, except when obliged to do so. Rose, the elder, is twelve years old; she is like her father—the most like him of the whole group—but it is a granite head copied in ivory; all is softened in colour and line. Yorke himself has a harsh face—his daughter’s is not harsh, neither is it quite pretty; it is simple, childlike in feature; the round cheeks bloom: as to the gray eyes, they are otherwise than childlike; a serious soul lights them—a young soul yet, but it will mature, if the body lives; and neither father nor mother have a spirit to compare with it. Partaking of the essence of each, it will one day be better than either—stronger, much purer, more aspiring. Rose is a still, sometimes a stubborn, girl now. Her mother wants to make of her such a woman as she is herself—a woman of dark and dreary duties; and Rose has a mind full-set, thick-sown with the germs of ideas her mother never knew. It is agony to her often to have these ideas trampled on and repressed. She has never rebelled yet; but if hard driven, she will rebel one day, and then it will be once for all. Rose loves her father: her father does not rule her with a rod of iron; he is good to her. He sometimes fears she will not live, so bright are the sparks of intelligence which, at moments, flash from her glance and gleam in her language. This idea makes him often sadly tender to her.

He has no idea that little Jessy will die young, she is so gay and chattering, arch, original even now; passionate when provoked, but most affectionate if caressed; by turns gentle and rattling; exacting, yet generous; fearless—of her mother, for instance, whose irrationally hard and strict rule she has often defied—yet reliant on any who will help her. Jessy, with her little piquant face, engaging prattle, and winning ways, is made to be a pet, and her father’s pet she accordingly is. It is odd that the doll should resemble her mother feature by feature, as Rose resembles her father, and yet the physiognomy—how different!

Mr. Yorke, if a magic mirror were now held before you, and if therein were shown you your two daughters as they will be twenty years from this night, what would you think? The magic mirror is here: you shall learn their destinies—and first that of your little life, Jessy.

Do you know this place? No, you never saw it; but you recognize the nature of these trees, this foliage—the cypress, the willow, the yew. Stone crosses like these are not unfamiliar to you, nor are these dim garlands of everlasting flowers. Here is the place—green sod and a gray marble headstone. Jessy sleeps below. She lived through an April day; much loved was she, much loving. She often, in her brief life, shed tears, she had frequent sorrows; she smiled between, gladdening whatever saw her. Her death was tranquil and happy in Rose’s guardian arms, for Rose had been her stay and defence through many trials. The dying and the watching English girls were at that hour alone in a foreign country, and the soil of that country gave Jessy a grave.

Now, behold Rose two years later. The crosses and garlands looked strange, but the hills and woods of this landscape look still stranger. This, indeed, is far from England; remote must be the shores which wear that wild, luxuriant aspect. This is some virgin solitude. Unknown birds flutter round the skirts of that forest; no European river this, on whose banks Rose sits thinking. The little quiet Yorkshire girl is a lonely emigrant in some region of the southern hemisphere. Will she ever come back?”

This is beautifully written of course, as we’d expect from Charlotte, but it shows an exact portrait of the Red House and the family within it. It’s especially moving for two reasons, the portraits of Jessy Yorke and Rose Yorke show the autobiographical elements to this novel.

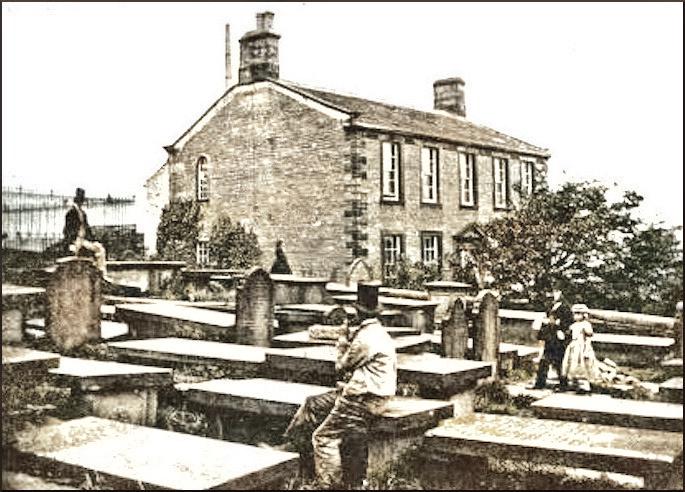

Jessy was in fact Martha Taylor, the younger sister who was deeply loved by Charlotte, and who died in a time of promise when Mary, Martha, Charlotte and Emily Brontë were all at school in Brussels. So much did this loss affect Charlotte that she also included a depiction of it in her first written novel ‘The Professor’. Charlotte’s words of love and loss are now depicted on the Martha Taylor memorial at the foot of Mary’s grave in Gomersal churchyard (alas, Martha’s grave in Brussels has long ago been concreted over – a Kirklees-like move): ‘Much loved was she, much loving.’

Rose Yorke is Mary Taylor, and we see the second Taylor tragedy as far as Charlotte was concerned: ‘the little quiet Yorkshire girl is a lonely emigrant in some region of the southern hemisphere. Will she ever come back?’

By this time, Mary Taylor had indeed emigrated to New Zealand, where she launched a successful business. Charlotte wrote at the time of this loss of her friend: ‘to me it is something as if a great planet has fallen out of the sky.’ By the time Mary returned to England, and to Gomersal, Charlotte Brontë was dead, as were all of her siblings that Mary had once known.

Mary Taylor was an incredible woman in her own right: a proto-feminist, a novelist in her own right, an adventurer and traveller. In many ways her life bears striking similarities to that of Anne Lister. Mary too preferred female company in later life, living with a succession of Swiss maids, and, just like Anne, she was also a pioneer of female mountain climbing in the Alps – as can be seen in this remarkable photograph.

Of course there is one big difference: Anne Lister’s home of Shibden Hall has been cherished by Calderdale Council, the neighbouring council to Kirklees, and it is now a major tourist attraction and a jewel in the cultural crown of Halifax. It’s not too late for Kirklees to do the same for the Red House, but it nearly is. The interior so beloved of Charlotte Brontë is now empty, where once it held glorious exhibits. The stained glass window of Shakespeare mentioned above has now been removed and is in the Brontë Parsonage Museum.

I’m proud to have been asked to help the Red House Revival community group, and this weekend I’ll be setting up a website for the group and the house – www.bronteredhouse.co.uk. Let’s do the decent thing and open this beautiful treasure of a house to the public once more. We can’t afford to let it rot. A Kirklees spokesman said that closing the Red House was part of their program to ‘improve museum facilities in Kirklees.’ Improving them by closing them down, at a time when we need culture and community facilities more than ever before. Please sign the petition.