As we all know, the Brontë novels are all things of beauty, but that can beauty can be enhanced still further when they are accompanied by wonderful illustrations too. In today’s post we’re going to be looking at perhaps the most beautiful set of Brontë books of them all, illustrated by a master of the genre – Edmund Dulac.

Charlotte, Emily and Anne Brontë were masters of writing about the human condition and how our minds work, which is why their books are as relevant today as they’ve ever been, but they were also masters of descriptive writing. That’s why their novels are so easily turned into magnificent adaptations on the big and little screens. We can all argue about which is our favourite adaptation of Jane Eyre, and we can all argue about which are the greatest illustrated editions too – which is why I added ‘perhaps’ in the last paragraph. All I can say for certain is that this set of ten books covering all seven Brontë novels (some occupying more than one volume) are among the greatest treasures in my own collection.

What makes the Brontë story so incredible, if we leave aside their incredible works of genius, is that their background was very different to so many writers of the time. Edmund Dulac too had a rather different career in mind to the one that saw him become one of the greatest book illustrators of all time. Born in Toulouse, France in 1882 he was at first a practising lawyer, but found that his love for art was his real passion even above the riches that a career in law could bring. After leaving law behind and training at a Paris art school, Dulac moved to England in 1904 and was quickly recognised for his mastery of the art nouveau style. His illustrations for The Arabian Nights and Stories From Hans Christian Andersen are recognised as works of genius in their own right, but his first commissioned work was illustrating the novels of the Brontë sisters for J. M. Dent in London.

These books are incredibly beautiful, from their elaborate covers with gold relief lettering to the ribbon page marker integrated within them. Each volume contains six illustrations, so I’m now going to introduce you to one picture from each Brontë novel and look at what it tells us about the story:

The Professor

The Professor was Charlotte Brontë’s first novel, but it remained unpublished in her lifetime. She borrowed and improved on the central theme in Villette, but in this picture we see a familiar image from all Charlotte’s works – the young woman who has fallen in love with the older man, but whose social position makes it seemingly impossible for that love to flourish. Where could Charlotte have got that idea from?

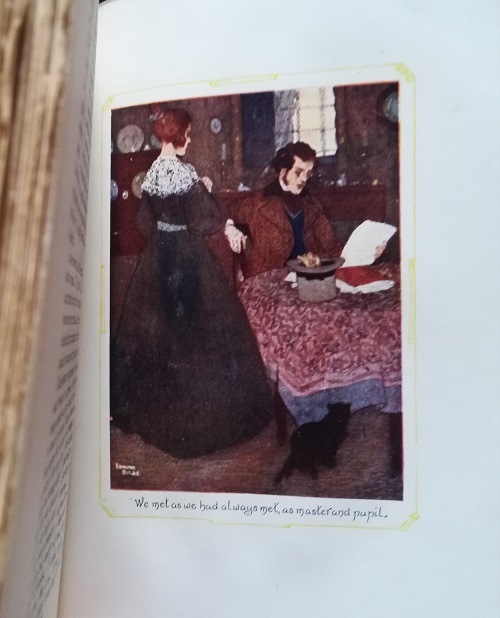

Agnes Grey

Agnes Grey by our beloved Anne Brontë is largely biographical in parts, dealing with the heroines two stints as a governess, just as Anne had herself served at Blake Hall and Thorp Green Hall. She allows herself, however, to imagine a happy, love filled ending for Agnes with Reverend Weston – for which we can surely read Anne and Reverend Weightman. In real life, Weightman’s untimely death denied her this love, but nothing could deny Anne’s writing. We know that Weightman was a kindly man who was renowned for helping the Haworth parishioners, and here we see Weston returning a cat he has saved from being shot, with a grateful owner and a besotted Agnes looking on.

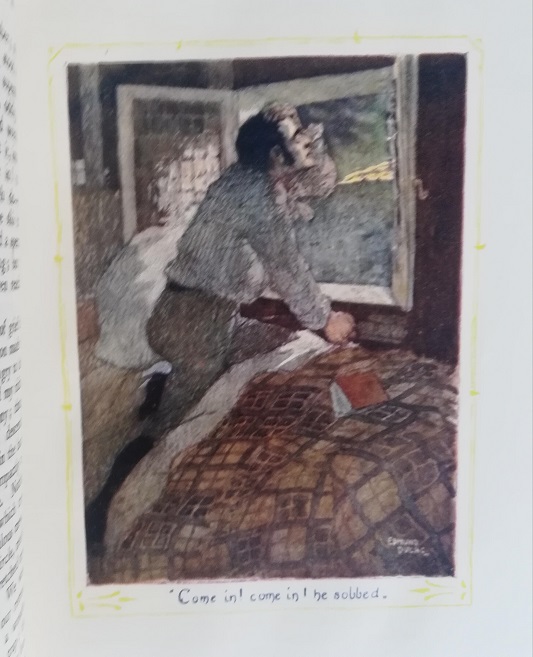

Wuthering Heights

Wuthering Heights is a book full of power, energy and magic – and Emily Brontë’s opening is one of the most memorable of them all. This illustration sees Dulac eschew his usual vibrancy, and create a moody, atmospheric image as Heathcliff flies to the window to bid the ghost of Catherine to return and haunt him, after Lockwood’s nocturnal encounter.

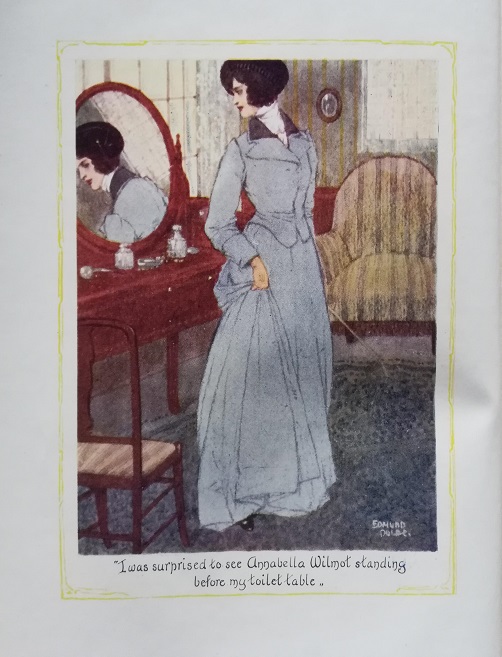

The Tenant Of Wildfell Hall

Anne Brontë used The Tenant Of Wildfell Hall to turn a spotlight on many of society’s ills, and especially on the abusive marriages that many women at that time were locked into. Among the outrages that Helen has to suffer, is the growing knowledge that her husband Arthur Huntingdon is having an affair with the haughty Annabella Wilmot, who later marries his best friend Lord Lowborough. Dulac here shows Helen catching Annabella in her room, but worse is to come.

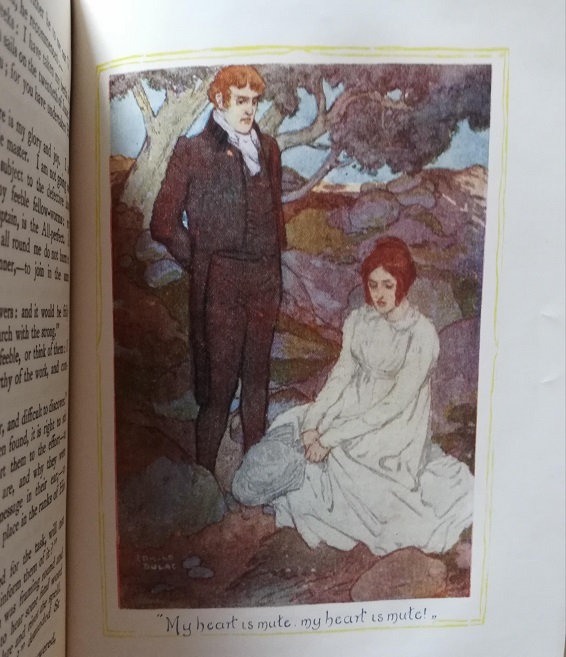

Jane Eyre

Charlotte Brontë could have given up after failing to find a publisher for The Professor, but giving up was never in Charlotte’s nature. Undaunted, she created an overnight sensation when her second novel Jane Eyre was published. One reason for its success, then and today, is that we can all sympathise with Jane, we can all see ourselves in her. She is downtrodden, underestimated, ignored and seemingly beset by ill fortune at every turn – but like her creator she has a mighty heart and a mighty soul, and eventually she will prevail. Here Dulac reveals Jane being browbeaten by her cousin St. John Rivers as he tries to convince her to marry him and leave for India. Her heart is mute because Rochester occupies it, and we all know what happens next.

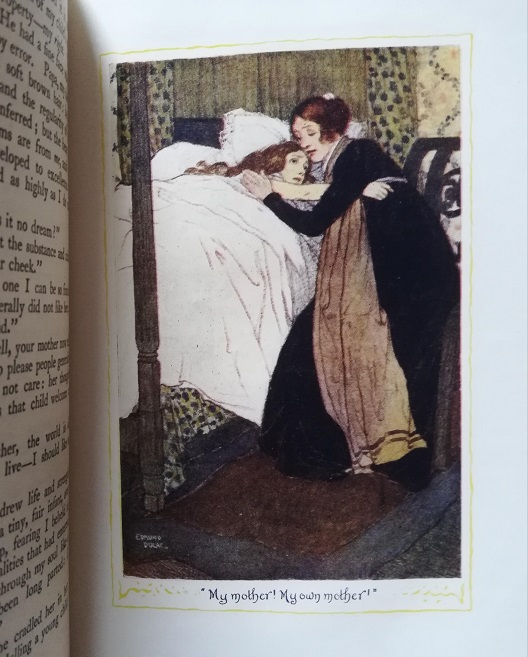

Shirley

I love Charlotte’s second novel Shirley because, disguised in name, she includes portraits of many of the people and places she has known – including her sister Anne under the guise of Caroline Helstone. Caroline is the real heroin of the novel (Shirley herself, based upon Emily, only appears many chapters in) and here we find Caroline at an emotional moment – she has discovered that Shirley’s governess Mrs Pryor’s real name is Agnes Helstone – she is her long lost mother. With those knowledge Caroline recovers from the illness that had taken her to the verge of death. Anne herself died whilst Charlotte was writing this novel, and she seems determined to save Anne on the page in a way that real life had denied her.

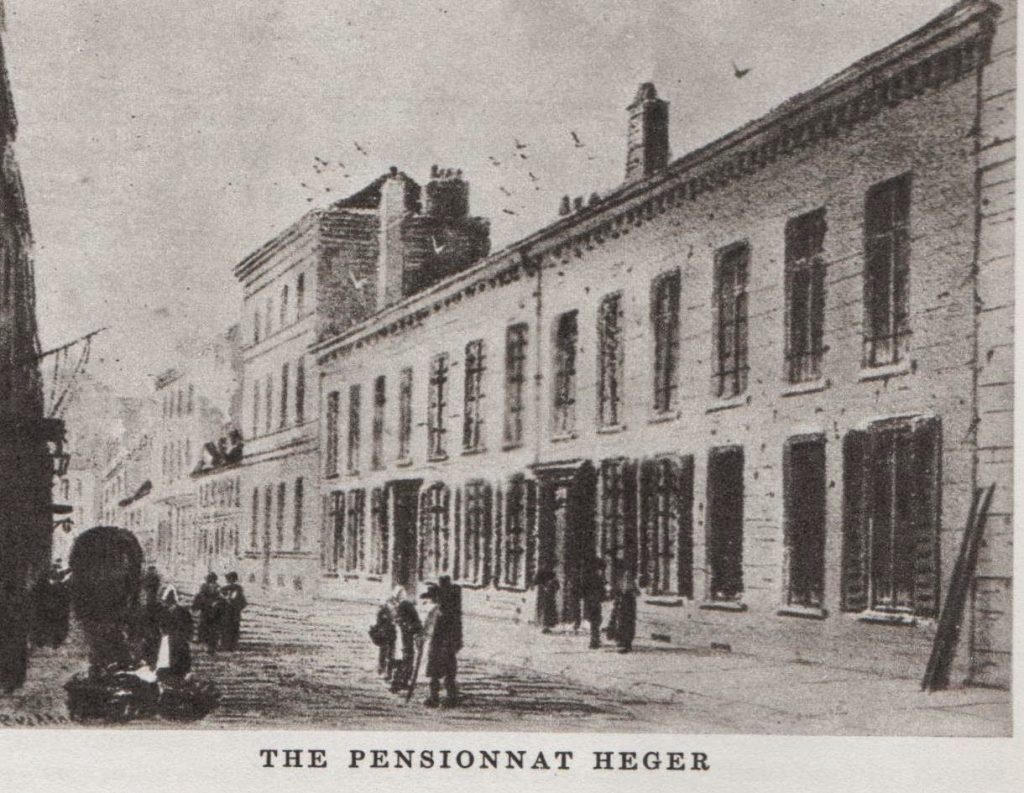

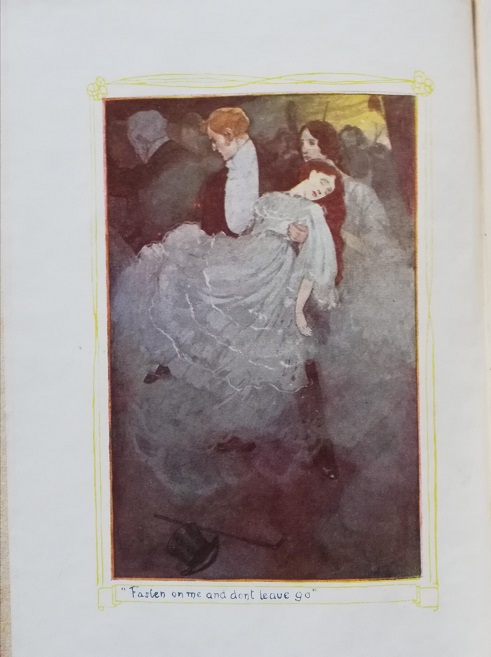

Villette

We return to Brussels for Villette, and this brilliant novel shows how far Charlotte’s powers had progressed since she was on similar territory with The Professor. Dulac’s illustration shows Lucy’s first love Dr. John rescuing a young woman after a theatre fire causes a stampede. She is the young Countess de Bassompierre, but in one of the novels many twists we discover that she is someone who Lucy had once known in very different circumstances (I won’t give this away, as it, like the novel as a whole, deserves to be read and enjoyed). The words are a perfect summary of Charlotte’s novel – Lucy wants someone she can rely on and fasten on to, but her hopes of love seem always adrift and then wrecked.

Edmund Dulac became a British citizen in 1914, and a pillar of the establishment who shortly before his death designed some of the most iconic stamps of Queen Elizabeth II. Like so many of us, however, his heart and mind was captured by those ladies of Haworth Parsonage.