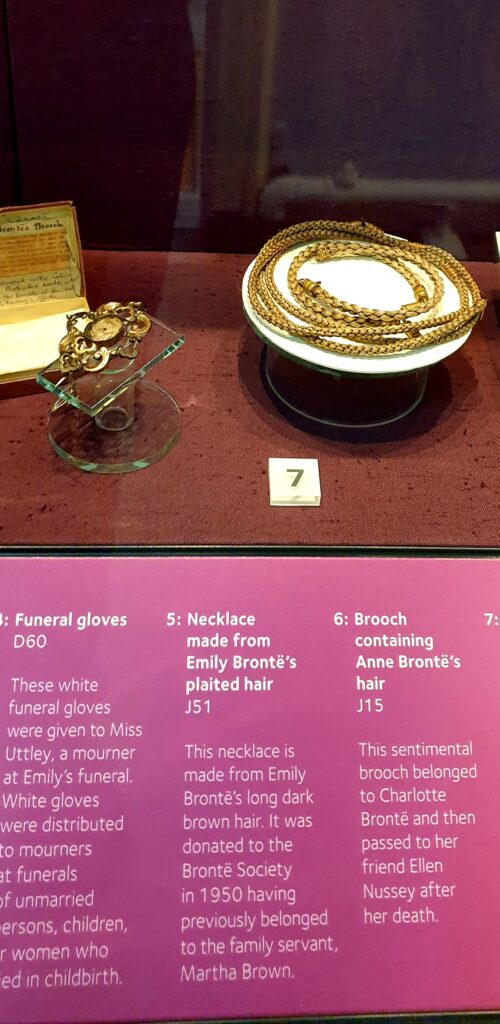

Exactly 125 years ago yesterday the death occurred of a woman central to the Brontë story: Ellen Nussey. Ellen Nussey was the best friend of Charlotte Brontë, and also a close friend of Anne Brontë and (probably uniquely) Emily Brontë. It was Ellen who travelled to Scarborough with Charlotte and Anne in 1849, and she who carried the dying Anne downstairs on her final day. Charlotte later sent Ellen this brooch and necklace made from Anne Brontë’s hair to remember her by:

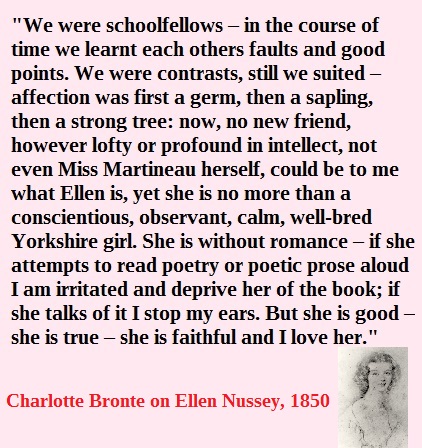

Ellen Nussey’s later years saw her working tirelessly to preserve and promote the Brontë legacy. She hoped to leave Charlotte Brontë’s letters to a national museum, or to turn them into a book, but she instead fell victim to fraudsters who ‘borrowed’ the letters and then sold them to collectors overseas. Nevertheless, it is thanks to Ellen Nussey keeping hundreds of Charlotte’s letters that we know so much about the Brontë family. Charlotte herself paid this simple yet beautiful tribute to Ellen while she was alive, but we will follow it with reports of and obituaries for Ellen that came after her death, aged 80, on 26th November 2022. You will also see photographs of Ellen Nussey throughout this post.

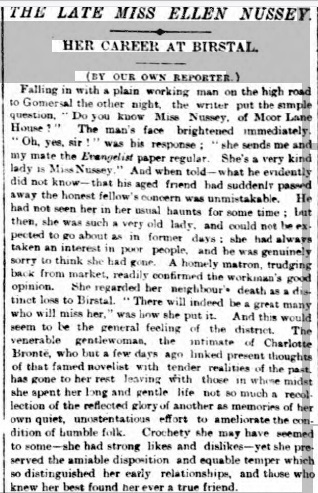

Yorkshire Post, 27th November 1897, “Death Of Miss Ellen Nussey: Friend Of Charlotte Brontë”

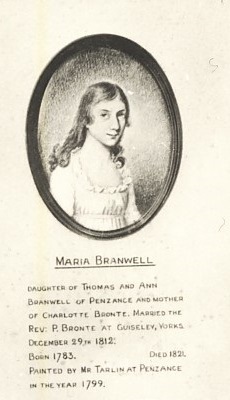

‘The death took place yesterday at Moor Lane House, Gomersal, of Miss Ellen Nussey, the schoolmate and friend of Charlotte Brontë, at whose marriage she officiated as first bridesmaid. Miss Nussey, who was born at the Rydings, Birstall, lived in the neighbourhood all her life, and at her death was 83 years of age [born a year after Charlotte, she was in fact 80]. The authoress was in her fifteenth year when she met Ellen Nussey at Miss Wooler’s school at Roe Head, and the friendship was a case of love at first sight. In the following year Charlotte paid her first visit to the Rydings, and their acquaintance ripened during the assistant-teachership period which followed. It was not, however, until July, of 1836, that Miss Nussey visited Haworth; and it was two years later (her brother’s proposal of marriage rejected meanwhile [Henry Nussey had proposed to Charlotte]) that they paid a visit together to Mr. Hudson’s, at Easton, near Bridlington.

Six years passed before they had much converse again [in fact, as the letters show, they were in constant correspondence], and then Charlotte was at [Ellen’s home] Brookroyd; nor was there another important meeting until just before the marriage in 1854. Thus it cannot be said that in a friendship unbroken during 24 years they spent a great deal of time together. Nevertheless, it is to Miss Nussey that the public owe the greater part of their knowledge of Charlotte Brontë’s life. The friends kept up a correspondence, in which there were 370 of Charlotte’s letters. When she died and Mrs. Gaskell undertook to write the biography, these were placed in her hands; and her Life Of Charlotte Brontë contains extracts from more than 100 of them, although Miss Nussey’s name is not mentioned. Afterwards Sir Wemyss Reid had access to them, and lastly they were placed in the hands of Mr. Clement Shorter [one of the men who defrauded Ellen] for the preparation of his brilliant book on Charlotte Brontë And Her Circle. Mr. Shorter, indeed, seems to say that the book was begun at Miss Nussey’s suggestion…

Her own personality has always been modestly kept in the background; but one receives from the correspondence a strong impression of her homely good sense, affectionate nature, and admirable simplicity.’

We will pass over a number of inaccuracies in this obituary, except for the article’s assertion that there was no ‘important meeting’ between Ellen and Charlotte for 12 years between 1842 and 1854. In fact there were many visits between the two in those years – many of them hugely significant, including their month in Hathersage together which was pivotal to the creation of Jane Eyre and their 1849 journey together to Scarborough with Anne Brontë to be there with Anne at her passing – obviously not an ‘important’ event as far as the obituary writer was concerned. The same newspaper provided a more personal tribute to Ellen two days later:

Yorkshire Post, 29th November 1897, “A West Riding Lady’s Interview With Miss Nussey”

‘A West Riding lady sends us the following notes of a recent interview she had with the late Miss Nussey:

“Like thousands of your readers, I read with much regret the news of the death of the venerable Miss Nussey, so intimately associated with the Brontë family. Miss Nussey has been waited upon by many persons for literary purposes, but I believe an interview I had with her during the autumn just passed was the last she was able to grant. It was in a state of great nervousness that I found myself at the inner door of Moor Lane House, Gomersal. With my heart in my mouth I saw Miss Nussey come forward to the door. All nervousness, however, vanished under the charming manners of this gracious old lady. Taking me into the drawing-room, I noticed she wore an old-fashioned brown silk dress and a rather modish cap of black, and white silk over her thick white hair. A noticeable feature was her bright eyes when she removed her spectacles. One of the first questions Miss Nussey asked was, ‘What religion are you?’ ‘Church of England, and from a long line of Church-people,’ I replied. My answer gratified her, and I soon found that she was an ardent, nay a passionate Church-woman.

One of the chief objects of my visit was to obtain her opinion on a portion of a letter said to be written by Charlotte Brontë to a correspondent unknown to me and all others to whom the document had been shown. What I had with me was a photograph. Upon inspecting it she said, ‘Undoubtedly the original is Charlotte’s handwriting.’ She soon decided to whom the letter had been addressed – Miss Leah Brooke, of Aldams House, Dewsbury, a former schoolfellow. Miss Nussey gave some interesting particulars about the then girl and her relatives. This led to a chat about Charlotte’s god-parents,the Rev. Thomas Atkinson and his wife, he the successor of Charlotte’s father in the vicarage of Hartshead. In Charlotte’s childhood she was a frequent visitor at their home. There was no vicarage house at Hartshead in those days, and the pair, who loved Charlotte dearly, bore the expense of her education at Roe Head…

Speaking of the Rev. P. Brontë, Miss Nussey said he was very fond of horses and dogs, but not to the extent his girls were; also that in his later years he became somewhat boastful of his conquests with ladies, a failing which much annoyed Charlotte, and which she always tried to check. He was a high-spirited man, full of courage.

In connection with her correspondence with Charlotte, Miss Nussey said she had often been badly treated, and I quite agreed with her when she informed me of the circumstances. This led me to tell her I had heard something of the kind before, and that I had felt diffident about seeking an interview, but that at last I had yielded, the suggestion being that I should ‘beard the lioness in her den.’ She laughed heartily, and exclaimed, ‘That’s exactly what I am, a lioness. I have to be, because of the way I have been treated.’ To me she was all kindness, and the interview throughout seemed to be mutually satisfactory. We parted, but she called me again to the house door, and then with a nervous air said, ‘Remember! All who have anything to do with the Brontës have had great trouble.’

I parted from the venerable lady with much admiration for her mental powers and great manners.”’

Yorkshire Post, 29th November 1897, “Ellen Nussey’s Last Moments”

‘Up to the very last Miss Nussey retained possession of her intellectual faculties. She had been ill for seven weeks with pleurisy, but on Thursday she was able to sit up a little. She was conversing quietly with her lady companion when the end came next day. A sudden spasm, and the long life was over.’

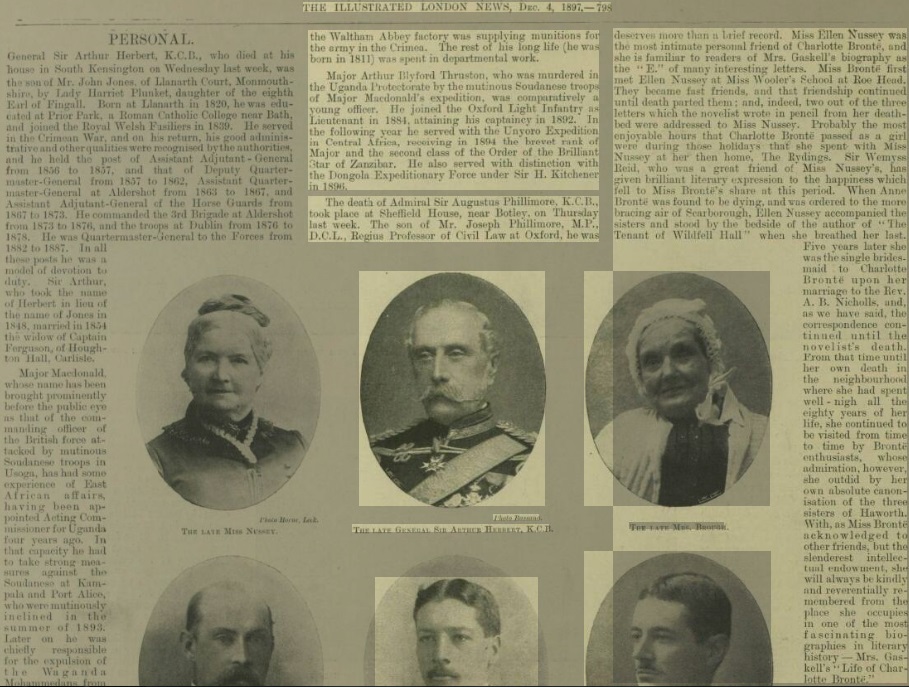

London Illustrated News, 4th December 1897

Yorkshire Post, 1st December 1897, “The Funeral Of Miss Ellen Nussey”

‘The funeral of Miss Ellen Nussey, the friend of Charlotte Brontë, took place yesterday in St. Peter’s Churchyard, Birstall. The weather was very inclement, and there was consequently not a very large attendance. The Brontë Society sent a wreath and was represented at the funeral.’

It’s sad that such a long life should end with few mourners at her funeral (St Peter’s church at Birstall, where she lies, is at the head of this post), just as Ellen herself had been one of only three mourners at the funeral of someone who lived a far shorter life: Anne Brontë. I hope to see you next week for another new Brontë blog post, and in the meantime I leave you with a final obituary which really sums up who Ellen Nussey was. Thank you Ellen Nussey from all Brontë lovers, and for always being a kind and generous woman to those who needed it most.