On Friday I went to see a show called ‘The Secrets Of The Selkies’ at Sheffield’s Kelham Island Museum. Fronted by Dr. Fay Hield, it was a magical performance encapsulating beautiful folk music, spoken word, animation and film – with a questions and answer session and a selkie sing along to finish. A great time was had by all, and it allowed the audience to immerse themselves in selkies, faeries and folklore in general. Selkies, if you didn’t already know, are seal like creatures who can shed their skins, come to land and live life as a human – but they always have a longing to return to their watery origins! The event made me think of the impact of faerie tales and folklore upon the Brontës, and its appearance in their work, so that’s what we’re going to look at today.

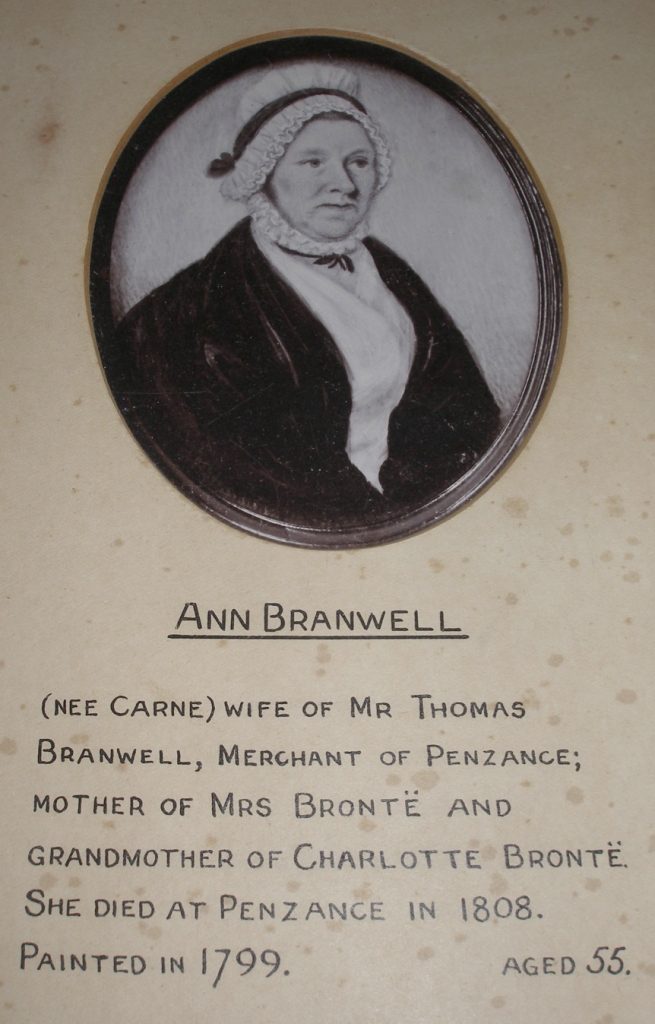

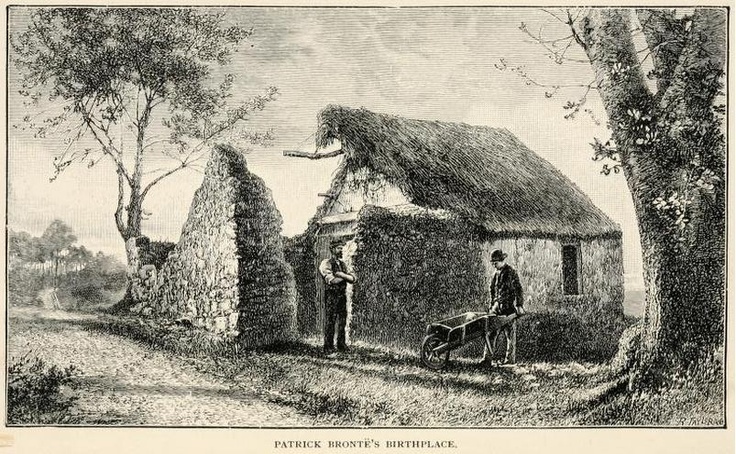

The Brontës might be seen as Yorkshire through and through, but they had double Celtic influences. Their father Patrick was Irish, and their mother Maria was Cornish (and of course they were then raised by their Cornish aunt Elizabeth after her untimely death). That’s a powerful combination, and it means they were exposed to myths and legends from an early age. It’s something that lovers of Brontë books can all be thankful for!

We know that faithful old parsonage servant Tabby Aykroyd regaled the children with the folklore of Pennine Yorkshire, including stories of changelings – faerie children who had been switched with a human child. This influence can clearly be seen in Emily Brontë’s Heathcliff – the child who appears out of nowhere, with no family background, and proceeds to wreak havoc in his new home.

It may seem strange then that although ‘changeling’ appears twice in ‘Wuthering Heights’ on neither occasion does it refer to Heathcliff. We see it applied to Linton on the eve of his wedding, forced upon him by Heathcliff: “‘Take you with her, pitiful changeling!’ I exclaimed. ‘You marry? Why, the man is mad! or he thinks us fools, every one.’”

We also see it applied to Catherine, or at least the ghost of her, after the narrator Lockwood has endured his night of torment in the box bed: “’And that minx, Catherine Linton, or Earnshaw, or however she was called—she must have been a changeling—wicked little soul! She told me she had been walking the earth these twenty years: a just punishment for her mortal transgressions, I’ve no doubt!’”

As we shall see, this is far from the only folklore in the tale, as Emily’s novel revels in it. In this most brilliant of novels we also see the clear Cornish influence, however, which must have come from her Aunt Branwell. Cornwall was a land steeped in lore and legend, although in 1824 the Cornish historian Samuel Drew was already bemoaning a change in attitudes:

“The age of piskays, like that of chivalry, is gone. There is, perhaps, at present hardly a house they are reputed to visit. They neither steal children, nor displace domestic articles. Even the fields and lanes which they formerly frequented seem to be nearly forsaken. Their music is rarely heard; and they appear to have forgotten to attend their ancient midnight dance. The diffusion of knowledge, by which the people have been enlightened during the last half century, has considerably reduced the numbers of piskays; and even the few that remain, are evidently preparing to take their departure.”

Drew is talking metaphorically here, showing how increasing industrialisation in Cornwall was eroding old faiths in the little people of the land. It is not the piskays, or pixies as they are styled elsewhere, that are departing, but belief in them. Nevertheless, around the moors of Cornwall belief held on, and, as I found when I visited there last year, the Brontë motherland of Penzance remains a place where old customs are cherished and celebrated.

Four hundred miles separates them, but Penzance and Haworth have a surprising amount in common, not least the mysterious moors which envelop them. On the moors outside Penzance stands an ancient round stone with a hole in it. Known as the Men-an-Tol, sickly children were brought to it and passed through the hole nine times to be cured – for as we all know, nine is the number of magic. It was also said that if a woman crawls through it backwards on a night of the full moon she will soon become pregnant.

This Men-an-Tol legend bears great similarity to a similar ancient stone structure called Ponden Kirk. This is a large stone column with a hollow hole at ground level. Legend says that if a couple crawl through it together and marry within a year they will have a child, but if they fail to marry the woman is cursed to die. Ponden Kirk is not on the Cornish Moors, it’s on the Pennine Moors, a short walk from Haworth and a place where Emily and Anne Brontë often walked to. It too features in ‘Wuthering Heights’, under the name of Penistone Crag, where Emily demonstrates the truth in its ancient legend:

“This bed is the fairy cave under Penistone Crag, and you are gathering elf-bolts to hurt our heifers; pretending, while I am near, that they are only locks of wool. That’s what you’ll come to fifty years hence: I know you are not so now. I’m not wandering, you’re mistaken, or I should believe you really were that withered hag, and I should think I was under Penistone Crag.’”

Catherine is delirious on her death bed, a death bed that will yield up Cathy. She crawled through the crag with Heathcliff but did not marry him, and now she has to die.

‘Wuthering Heights’ is infused with magic, you could say it casts a spell of its very own. Certainly it has held me in its power since I first read it aged 18, and now I believe it to be the most magical novel ever written.

Emily is not the only Brontë who features folklore in her work however, for we also see it appearing regularly in Charlotte’s writing. There’s the ghost nun in ‘Villette’ for instance, and in ‘Jane Eyre’ we also encounter a gytrash!:

“I heard a rush under the hedge, and close by glided a great dog, whose black and white colour made him a distinct object against the trees. It was exactly one form of Bessie’s Gytrash… Nothing ever rode the Gytrash: it was always alone.”

This is actually Rochester’s huge dog Pilot, rather than a gytrash – a demonic dog! Charlotte had heard tales of the gytrash from Tabby, possibly, but with certainty from the Heatons of Ponden Hall. The Hall was often visited by the Brontë children, not least for the attractions of its huge library, and it is reputedly haunted by its very own gytrash.

Perhaps Charlotte’s most incredible reference to folklore, however, comes in her little known ‘Willie Ellin‘, an unfinished novel from which we have only a few fragments. One of these fragments, however, contains a description of a faerie like creature who seems connected to the building at the centre of the book:

“In other countries, and in distant times, it is possible that more of my kind might have been attracted to human dwellings – hut or mansion – and secretly taken them in lease, than for these hundred years past have been known to make their home in such abodes. Yet we were always few, our presence rare, its signs faint, and its proofs difficult to seize…

Who am I? Was I owner of the house? No. Was I its resident tenant, taking it perhaps on lease, and paying the rent? No. Was I a child of the family? No. A servant? No. Ask me no more questions for they are difficult to meet. I was there, and it was my house.

I recollect the first hour that I knew it. I came to consciousness at a moment within the rim of twilight. I came upward out of earth – not downward from heaven, and what first welcomed and seemed to aid me to life was a large disk high over me, a globule, clear, cragged, and desolate. I saw the moon before I could see the sky; but that too, night-veiled and star-inspired, soon opened for me. A sweet silence watched my birth-hour. I took affection for this mossy spot, I stole all through building and nook of land. In the mild beam and pure humidity of a midsummer night I found my seal and sign printed here in dew and there in moonbeam on roof and lawn of Ellin Balcony.

I do not know that ever I was knit with humanity, or was mixed with the mystery of existence as men or women know it. Yet had no mortal relic slumbered near the Balcony, should I have risen Would Night, my mother, have borne me, unwedded to a certain vital, mortal essence ? Tears had watered this ground; great sorrows and strong feelings had gathered here. Could a colder soil, drenched only with rain and visited only by airs and shadows, have yielded me as its produce? I even think that some one sleeper threw me out of a great labouring heart which had toiled terribly through his thirty, or sixty, or fourscore years of work, had lived and throbbed strongly, stood still while yet in vigour, and buried, yet warm and scarce arrested, had thrown forth its unslackened glow and ill-checked action in an essence bodiless and incomplete, yet penetrative and subtle.

I believe this because my relations to men were so limited. To millions I felt no tie, found no approach; to tens I might draw gently. Whether units existed that could more actively attract it, yet lay with time and chance to show. Whoever in my early days were the inmates of Ellin Balcony, on me they made no impression. I knew every stone in the walls. I knew the neighbourhood – the knolls, the lanes, the turfed wastes, all vegetable growth, field flowers, hedge plants, yellow gorse and broom, foxglove springing bright out of stony soil, ivy on ground or wall. I distinguished and now remember these things very well. I knew the seasons, the faces of summer and winter. Spring and autumn were familiar in their skies; night, day, and the hours were all acquaintances. Storm and fair weather complete my reminiscences. I cannot recall anything human, and yet humanity was in the house. Experience now tells me that it must have been busy, bustling humanity, an alert current of life flowing out after to towns and thickly peopled scenes, returning thence with accessions – life circulating in a free, ordinary channel, never stealing slow under the banks of thought, never winding in deeps, but coursing parallel with populous highways. At last, I suppose, this practical daily life forsook retirement and went permanently away to the towns which were its natural sphere. This departure made no difference to me, except that I remember looking at the sun and listening to the wind with a new holiday feeling of unconstraint.

About this time I first added a cognisance of the individual human being to a vague impression of a human race existing. A solitary old woman became housekeeper of Ellin Balcony. She used to feed a great dog chained in the now empty yard, to close and open shutters, to knit a great deal, and read and think a little. I believe it was because she did think, however little, that I had the power to perceive her presence. Those who had lived here before her never thought, and into an existence all material I could not enter.”

This is a tale unlike any other in the Brontë canon, if only Charlotte could have written more of it and explained the mytery of this faery-like spirit.

So, we see folklore throughout the Brontë writing. It inspired the Brontë siblings and it inspires us today, for what is this life if we can’t devote a little of it to the magical and mysterious? There are no selkies in the Brontë novels, but then were the Brontë characters selkies themselves, of a kind? Jane Eyre sheds her governess skin and becomes a wealthy heiress with the man she loves; Helen Graham sheds her skin as an abused wife and becomes a strong, independent woman; Heathcliff sheds – well, not all characters can be selkies. But we can all be a little selkie-like ourselves, and devote time to losing ourselves in the magic of literature – our very own step from boring land into the promise-filled water of our imaginations.