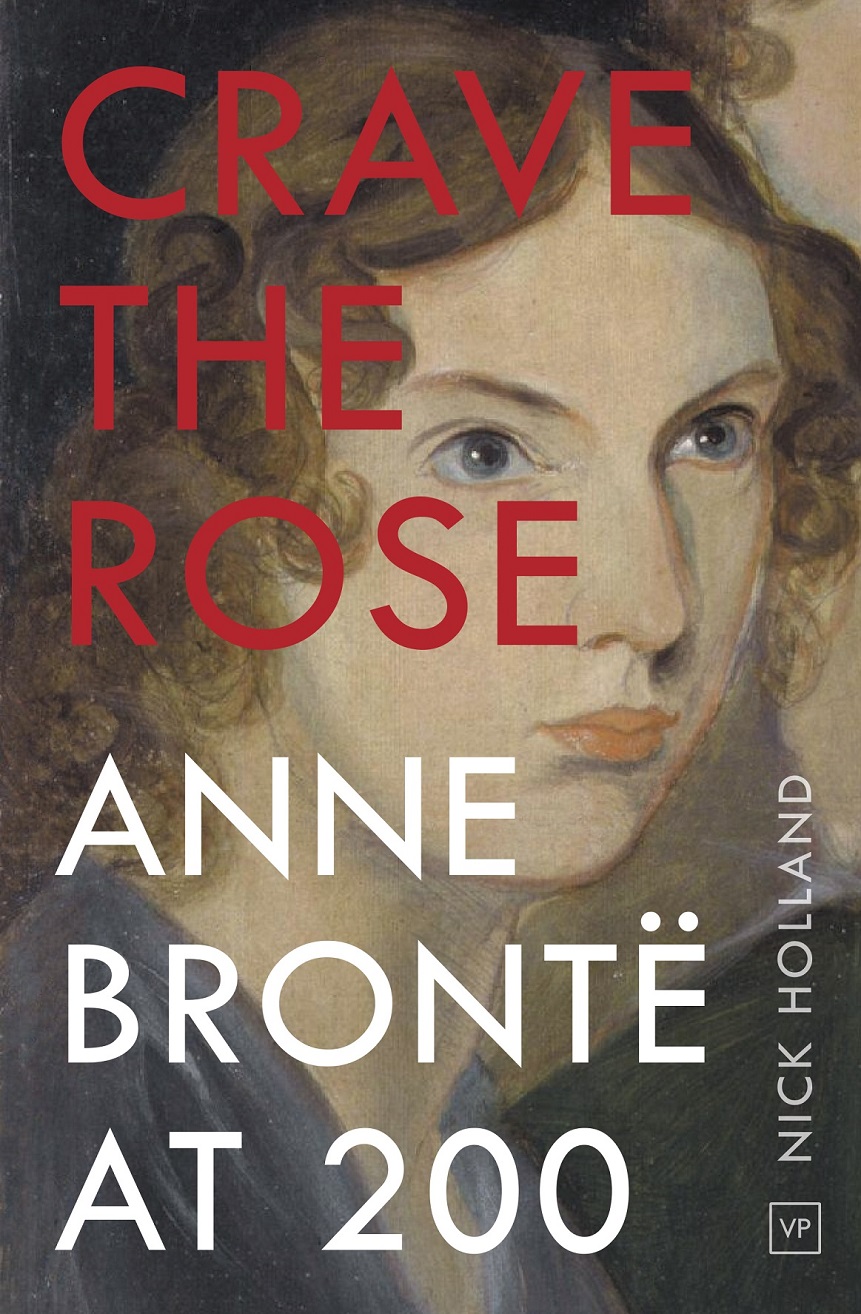

Some Brontë memories and anniversaries are happy, some not so happy; unfortunately this week has marked the anniversary of a particularly tragic event in the Anne Brontë story, for Anne Brontë died in Scarborough on 28th May 1849.

Today is the 172nd anniversary of the funeral and interment of Anne, as she was buried on 30th May in the churchyard of St. Mary’s churchyard in Scarborough – above her final resting place looms the castle hill topped by fortified ruins; below it the road runs down to the sands, with the pebbles and shells Anne loved to collect, and the ever ebbing sea.

We have also just passed another sad anniversary, for on the 28th May 1852 Charlotte Brontë returned to Scarborough for the first time since her sister’s death there exactly three years earlier. It was the first time that she’d seen Anne’s headstone, and what she saw appalled her: we’re going to take a look at that in today’s post.

We get our initial information of both the visit and the errors in a letter Charlotte sent from Filey on 6th June 1852 to her great friend Ellen Nussey:

‘Dear Ellen, I am at Filey utterly alone. Do not be angry. The step is right. I considered it and resolved on it with due deliberation. Change of air was necessary; there were reasons why I should not go to the South and why I should come here. On Friday I went to Scarboro’, visited the church-yard and stone – it must be refaced and re-lettered – there are 5 errors. I gave the necessary directions – that duty then is done – long has it lain heavy on my mind – and that was a pilgrimage I felt I could only make alone.’

One error still remains today; the original headstone is greatly eroded now, but on the ground nearby is a plinth bearing the inscription, placed there by the Brontë Society in 2011: ‘Here lie the remains of Anne Brontë, Daughter of the Revd P Brontë, Incumbent of Haworth, Yorkshire, She died Aged 28 May 28th 1849.’

Anne was, of course, 29 at the time of her death, but Charlotte Brontë was never good at remembering ages or birthdays (including her own). A monument to Anne that was placed in Haworth church, no longer extant, read: ‘This stone is also dedicated to the memory of Anne Brontë, youngest daughter of the Rev. P. Brontë, A.B. She died, aged 27 years, May 28th, 1849, and was buried at the old church, Scarboro’

So we know that the stonemasons recorded Anne’s age incorrectly, but what were the other four errors (or, more probably, five errors as Charlotte didn’t seem to have spotted the age error)? There is no record of them, so we shall never know. Obvious possibilities include the spellings of Anne (perhaps the ‘e’ was ommitted), Brontë and Haworth. With little else remaining on the inscription it seems they must have recorded the date of death incorrectly too. Indeed, with five or six errors out of a total of 24 words, it is probable that every fact recorded on the stone was wrong in some way.

Returning to Scarborough and seeing Anne’s headstone for the first time in three years must have been incredibly tough for Charlotte, so we can easily imagine her heartache upon seeing a headstone full of errors.

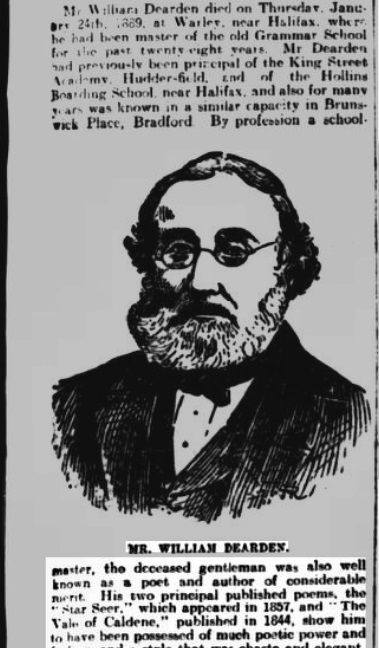

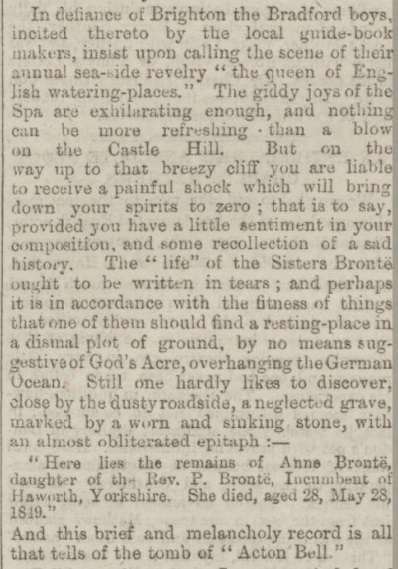

Unfortunately, time and the saline air of Scarborough have taken their toll on Anne’s headstone. Year by year it becomes less legible, and further scraps of its facing break away. Even in the 1870s, however, people were noticing the erosion of the inscription and poor condition of the headstone, as this extract from the ‘Dundee Evening Telegraph’ of 28th August 1878 shows:

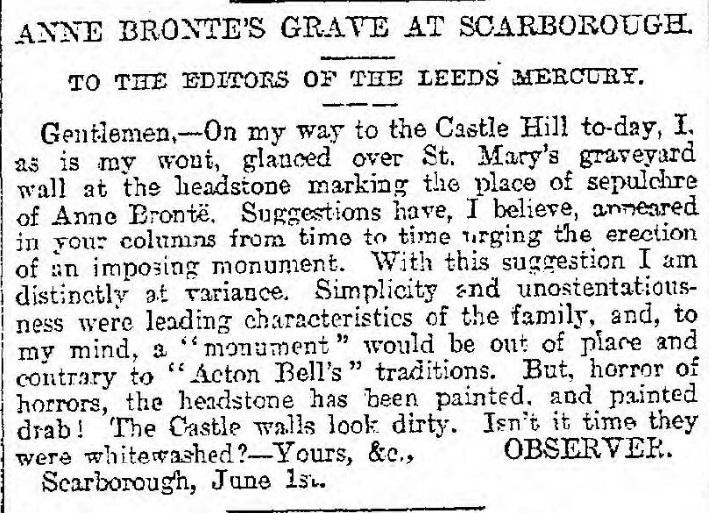

As we see from this letter in the Leeds Mercury of 3rd June 1895, the council took steps to improve the headstone – by painting it. It was less than successful:

The inscription on Anne Bronte’s headstone will soon be completely lost to the elements, but her true memorial is her novels and poems, and they will endure forever. Let us look then not with sadness at these tragic anniversaries, but with happiness and gratitude for all Anne left us.

I will see you next Sunday for a special Brontë blog post, as thanks to Sotheby’s I can share with you some of the treasures of their Brontë auction taking place this summer.