This weekend in 1820 was a day of celebration in the Brontë household of Thornton, for 203 years ago yesterday marked the anniversary of the baptism of Anne Brontë. We’ll look at this in today’s post and we’ll also take a look at a very different kind of anniversary, as today is the 137th anniversary of Brontë servant Nancy de Garrs.

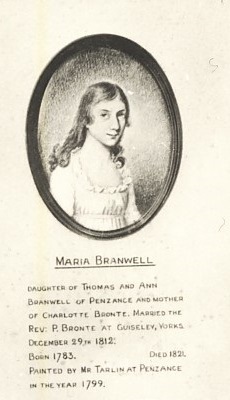

Anne was the sixth and final child of Patrick and Maria Brontë, and she was born in Thornton on the outskirts of Bradford on 17th January 1820. It was over two months until Anne was baptised, but then as we shall see the Brontë family were rather busy at this time!

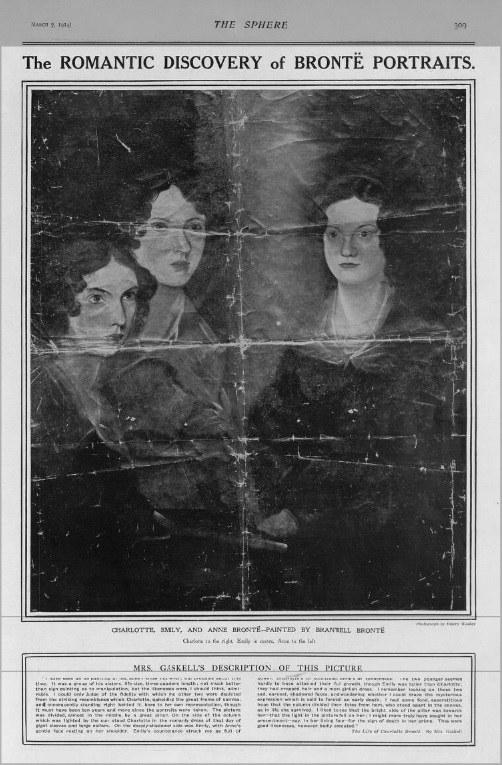

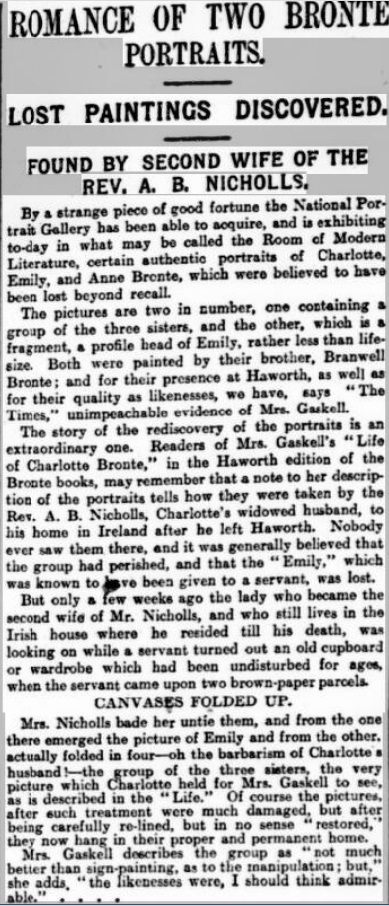

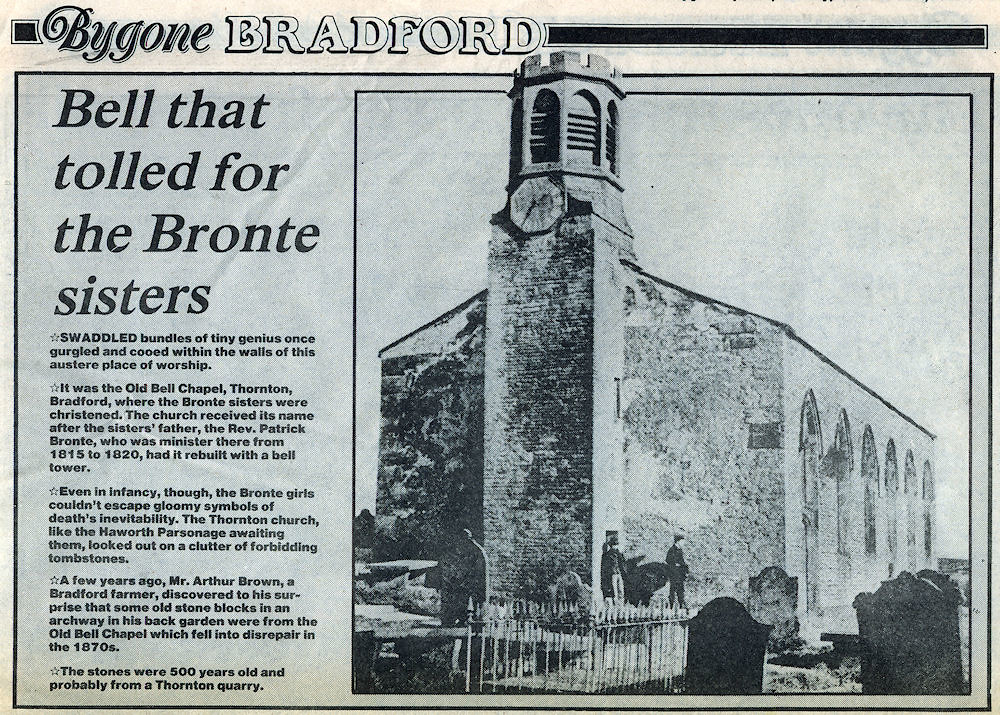

Patrick was, of course, at that time the minister of the local Church of England church, St. James’s. It was Patrick who had a bell tower erected at the church, and although it is now a (lovingly maintained) ruin it still bears the appellation of Thornton Old Bell Chapel – that’s it in modern times at the head of this post and pictured in its prime below:

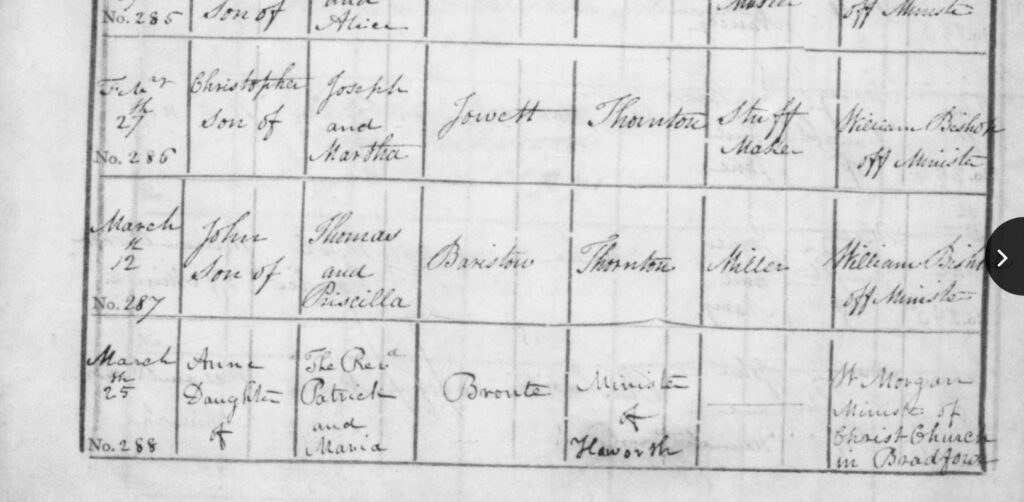

On the morning of the 25th of March 1820 we can imagine the Brontë family and their servants making the short walk downhill from their Market Street parsonage to the church which looked out onto the moors. Waiting for them at the church were the minister who would be presiding over the baptism, Reverend William Morgan, and two very well chosen godmothers.

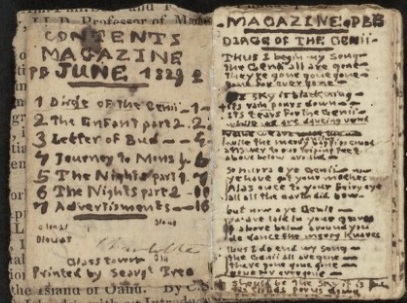

Morgan was curate of Christ Church in Bradford, and it is he who is named on the baptism record which is shown below, and which is still kept, and sometimes displayed, at the new St. James’s church, Thornton – across the road from what remains of the church the Brontës knew.

Morgan was a man pivotal to the Brontë story. Born in Wales in 1782, making him Patrick Brontë’s junior by five years, the two Anglican priests came to know each other when they were both curates in Wellington, Shropshire. Years later it was Morgan, by then in Yorkshire, who secured Patrick the position of examiner at Woodhouse Grove school near Leeds. Within six months of Patrick’s arrival he had married the school owner’s niece Maria Branwell and Morgan had married the school owner’s daughter Jane Fennell – Patrick and William not only acted as best man for each other during their dual wedding ceremony they were also the presiding minister for each other’s marriage!

William and Patrick remained close friends, and he was often called upon to preside over Brontë ceremonies. At first these were happy ones such as the 1812 wedding and the 1818 baptism of Emily Brontë which produced this beautiful baptism cup (unfortunately whilst there was probably a similar one for Anne it’s no longer extant). Alas, far too soon William Morgan was also called upon to conduct the funeral services of his friend’s children, the children he had once baptised.

Chosen as Anne’s godmothers were Elizabeth Firth, of nearby Kipping Hall, and her friend Fanny Outhwaite. We know that these two women supported Anne and her family all their lives. During the time that Anne and Charlotte were at Roe Head school, Mirfield they often visited the nearby Franks (as Elizabeth was called after marrying a Reverend Frank). Fanny Outhwaite died in 1849 and left Anne a generous bequest; it was this legacy which allowed Anne to travel to Scarborough for the final time in that very same year, as, alas, Anne too was reaching the end of her days.

The 1820 baptism would have been one of the highlights of the Brontë family’s time in Thornton, but it was also one of the last actions of their sojourn in the village. Less than a month later, on 20th April, the Brontë family said goodbye to Thornton and headed to a new parish six miles to the north-west across the moors; history was about to be made, and Haworth would never be the same again.

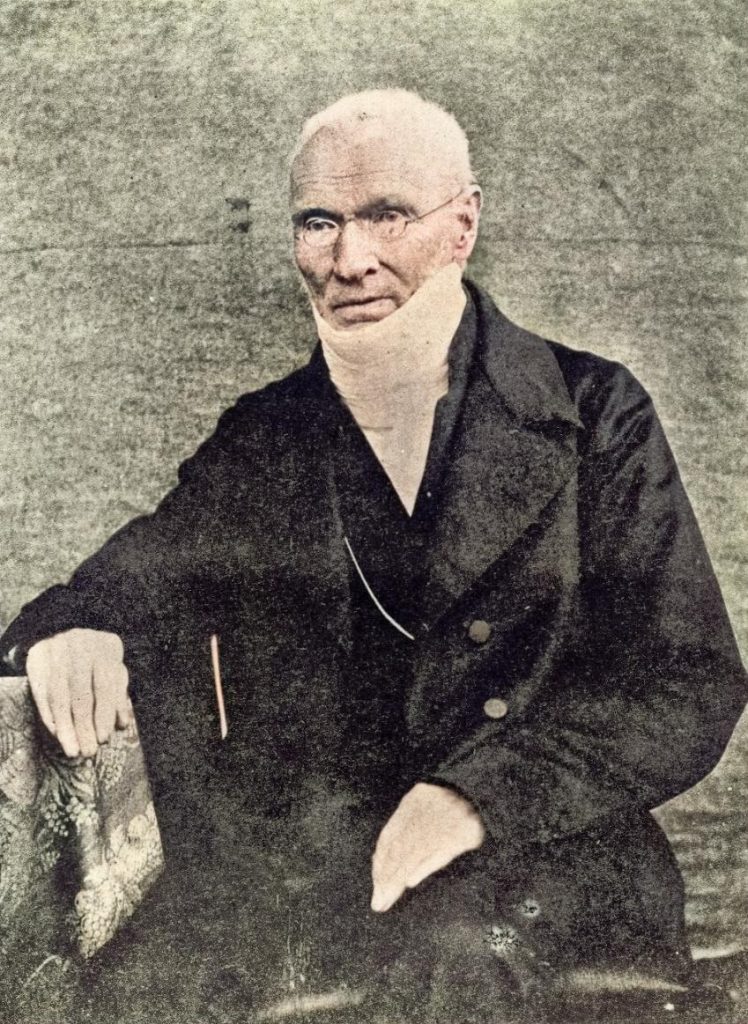

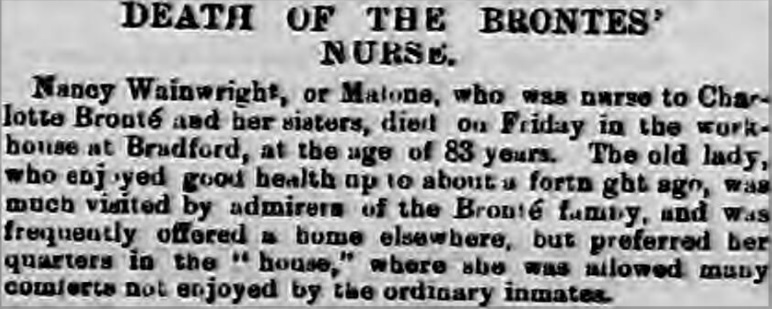

It seems likely that Thornton Parsonage servants Nancy and Sarah de Garrs. A very different anniversary has arrived today for the elder sister, for it was on this day in 1886 that Nancy Malone, formerly Nancy Wainwright and Nancy de Garrs (although commonly referred to in Brontë biographies as Nancy Garrs) died in a Bradford Workhouse. She was buried in an unmarked grave at Undercliffe Cemetery, but the wonderful team of volunteers at that cemetery have done a lot in recent years to give her the resting place she deserves, and to tell her remarkable story.

Sadly the Workhouse was the final habitation of many working class people of the time, but Nancy’s Brontë connection meant that she was given special treatment, including the right to receive visitors who wanted to talk to her about the genius children she had nursed. On more than one occasion Nancy was offered a home outside of the Workhouse,but she always say that she had grown used to it and wanted to stay there.

It is sometimes thought that Nancy was buried in a pauper’s grave, but that’s not the case. A benefactor named J. H. Widdop ensured that she was given a burial in her own plot, and flowers were laid on the spot. Also present at the funeral was the nurse who had looked after Nancy since her arrival at the workhouse. The nurse’s name may have brought to Nancy’s mind a happy day in March 1820, for she was called Mrs Morgan.

In one weekend we have seen the full circle of life in the Brontë story represented. Whatever life is bringing you at the moment I hope that happy times are approaching with the warmth of spring, and I hope to see you next week for another new Brontë blog post.