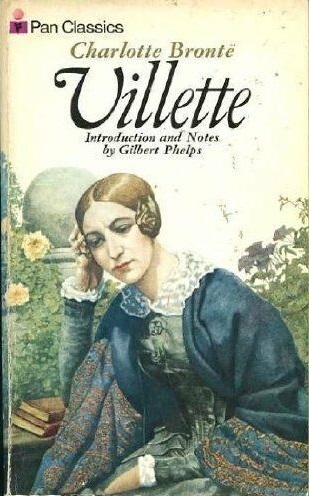

On this day in 1853 a remarkable piece of fiction was published: Villette. It was to be the final completed novel by Charlotte Brontë, and it was written at a time of intense personal struggle for her. Unlike during the composition of Jane Eyre and the first half of Shirley she was completely alone during Villette’s genesis, without her beloved sisters Emily and Anne to advise and inspire her. It was also a time when she was dealing with her father’s illnesses, and the aftermath of a failed proposal, as well as having to deal with her new found fame as a writer. We see all this and more in the subject of today’s post: five letters written around the time of the publication of Villette.

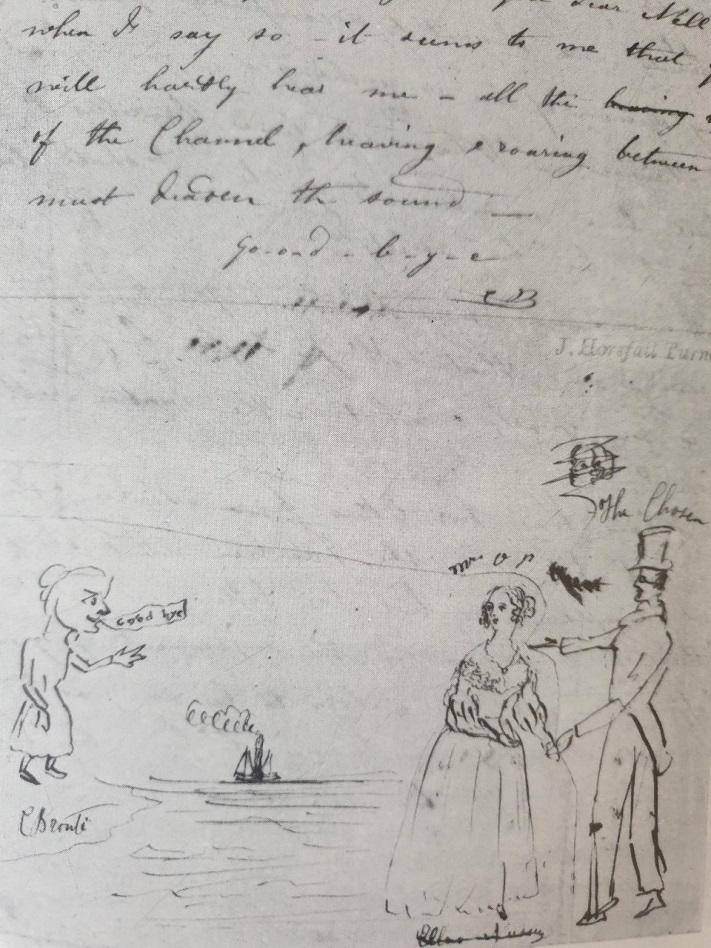

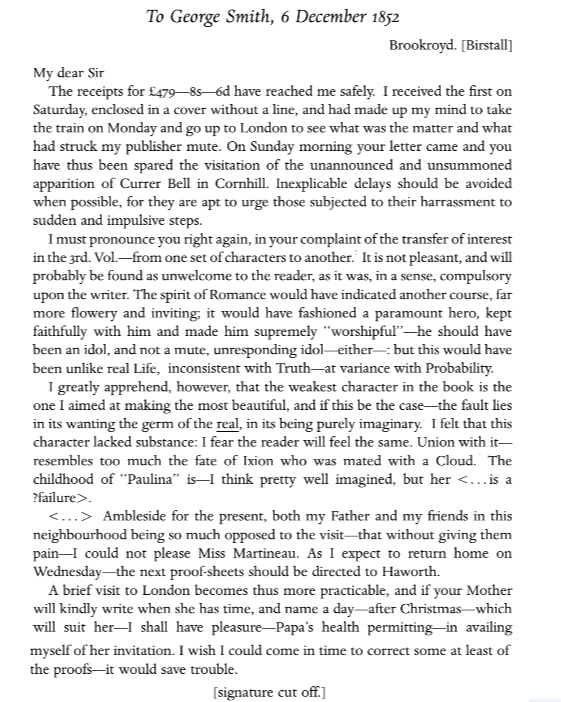

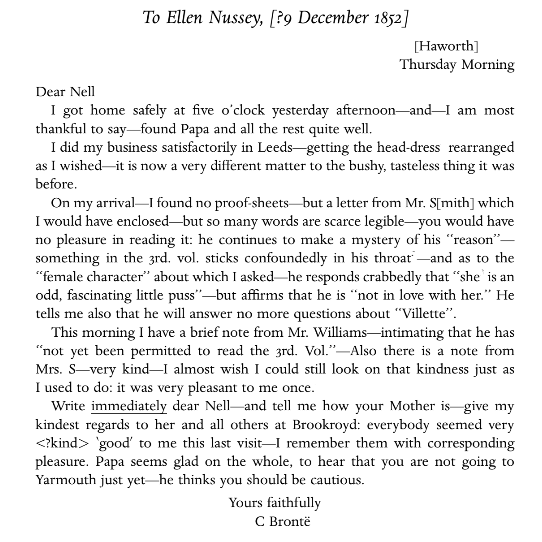

This letter to best friend Ellen Nussey from early December 1852 shows one of the recurring bones of contention that author and publisher had over Villette. Charlotte often liked to base her fictional characters upon people she knew well: so that the eponymous heroine of Shirley was based upon Emily Brontë and Caroline in the novel was based upon Anne Brontë. George Smith clearly recognised that he was the model for Graham Bretton – portrayed as a handsome yet selfish, and at times rather self-centred individual. Charlotte had once loved Smith, but her publisher’s engagement and marriage had placed a great strain on their relationship. This is also apparent in the earlier letter of 6th December to Smith himself – where once Charlotte would have been open with her publisher, she is now on the defensive.

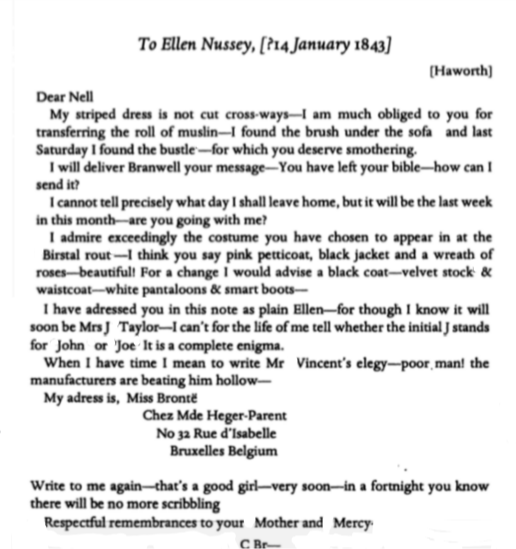

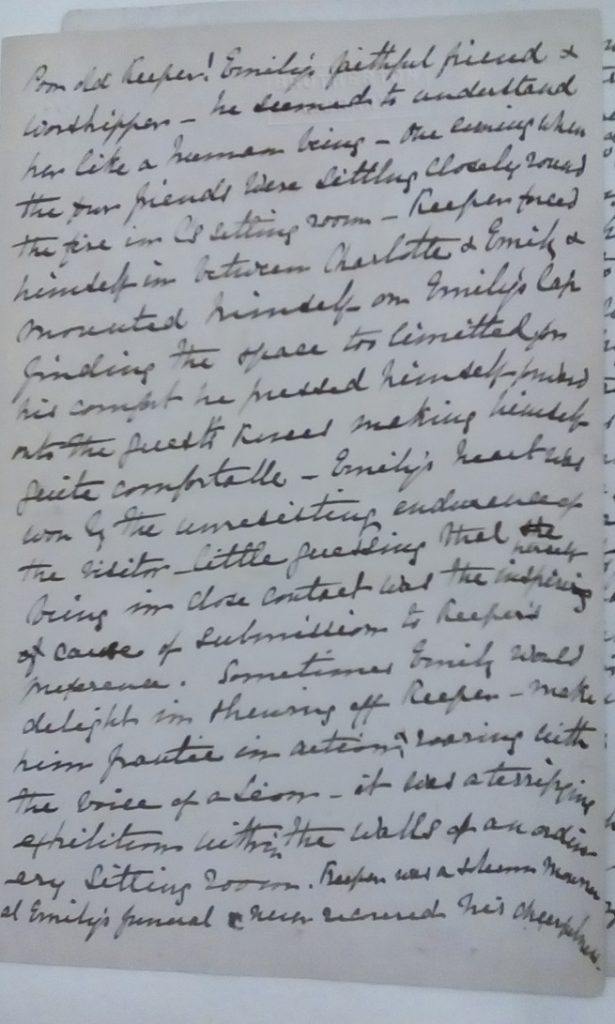

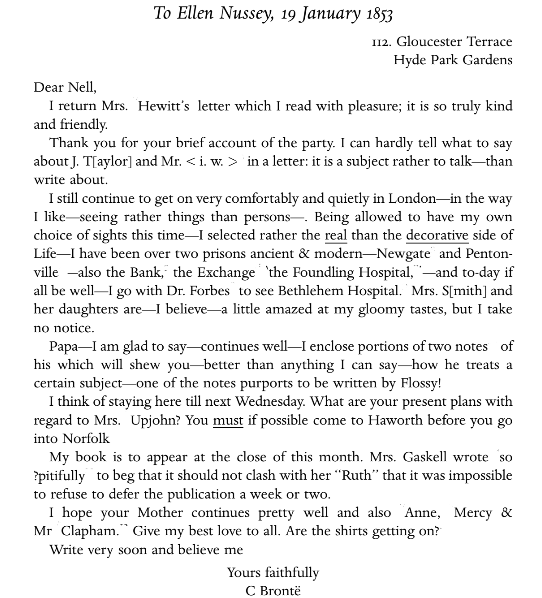

By 19th January 1853, Charlotte was staying in London with George Smith’s mother and sisters, but she realises now that her tastes are not in accord with theirs. Charlotte has, as usual during her stays in the capital, been offered tours of the city’s sights, but she is more interested in the extremes of humanity than the trappings of fashion or high culture. During this period she has also received a charming letter from Flossy, once Anne’s beloved pet spaniel and now in its fifth year in Charlotte’s care. Written by Patrick Brontë, its purpose is to warn Charlotte against trusting men – and in particular against trusting Arthur Bell Nicholls who recently proposed to Charlotte and was soundly rebuffed.

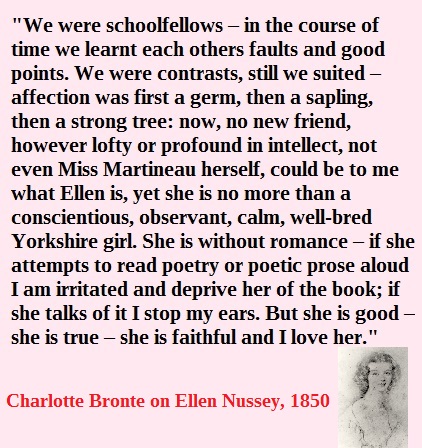

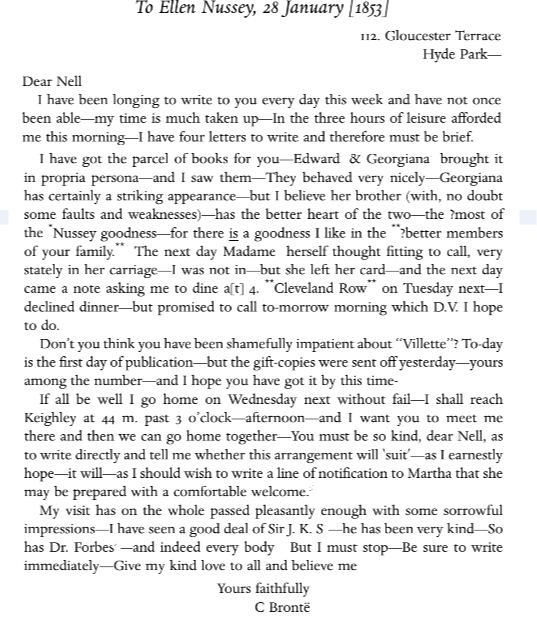

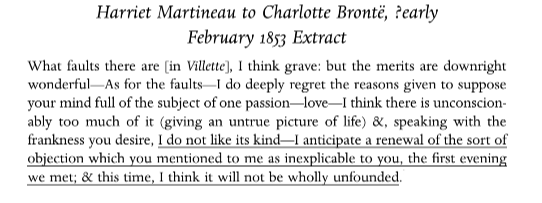

In the 28th January 1853 letter to Ellen we see that Villette has finally been published, but she didn’t have to wait long to hear an unfavourable reception – as we see from the fragment of a letter sent by Harriet Martineau. Charlotte had earlier asked Harriet to give her forthright opinion on the book, saying: “I kneel to Truth. Let her smite me on the cheek – good! The tears may spring to my eyes; but courage! There is the other side – hit again – right sharply!”

Nevertheless, Charlotte was dismayed by Harriet’s reaction to Villette, and in a later review written anonymously by Martineau which repeated the same criticism. The rebuke of Charlotte for being full of love (the book was clearly, after all, written heavily under the influence of her unrequited love for Monsieur Heger, her former teacher and colleague in Brussels) was too much for her to take – and the friendship between Charlotte Brontë and Harriet Martineau was at an end.

It was a book that Charlotte Brontë found difficult to write, and she found its reception hard to take at times, but Villette is a book that endures. It is an incredibly powerful book, incredibly moving in its still, silent power. It is a work of genius.

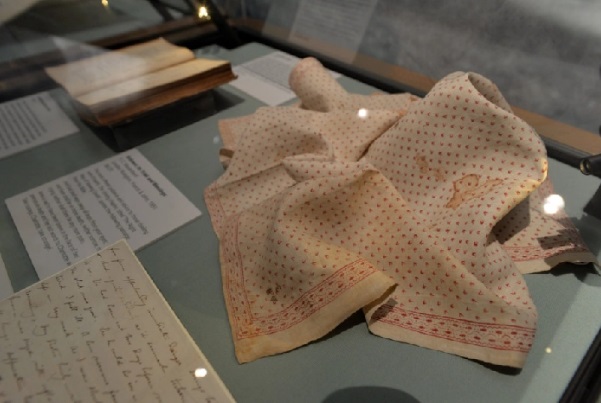

I can’t promise you a blog of genius, but I hope you will join me next Sunday for another new Brontë blog post. Incidentally, last week I failed to thank Vesna Armstrong for the incredible photo of Charlotte Brontë’s christening bonnet – my sincere apologies for that error on my part; Vesna is a fantastic photographer and Brontë enthusiast, so please do check out her work when you can.