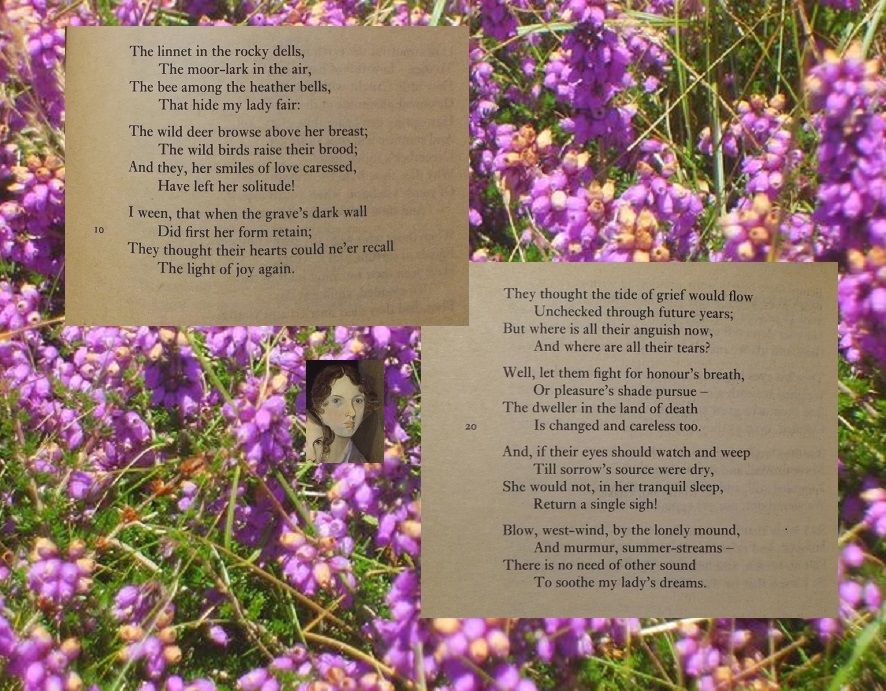

This weekend marked the anniversary of the funeral service and then burial of Anne Brontë in Scarborough. As you probably know, Anne is buried in a graveyard to the side of St. Mary’s church, in the shadow of Scarborough Castle and looking down towards the sea she loved. The funeral service, however, took place at Christchurch on Vernon Road, as the interior of St. Mary’s was being renovated at the time. The funeral was held on 30th May 1849, and Charlotte Brontë and Ellen Nussey had expected to be the only people in attendance. When they arrived at the church however they found one other person already there, and she was in the right place at the right time on many occasions throughout the Brontë story. We’re going to take a look at her today: Margaret Wooler.

Margaret Wooler first entered the Brontë tale on January 17th 1831, for on that day Charlotte started life as a pupil in Roe Head School in the hills above Mirfield. Miss Wooler, as she was known to her pupils, was headmistress and, in stark contrast to Charlotte’s first school at Cowan Bridge, she ran a kindly school that provided a high quality of education. She didn’t run it alone, however, and in its early days the school was a family concern.

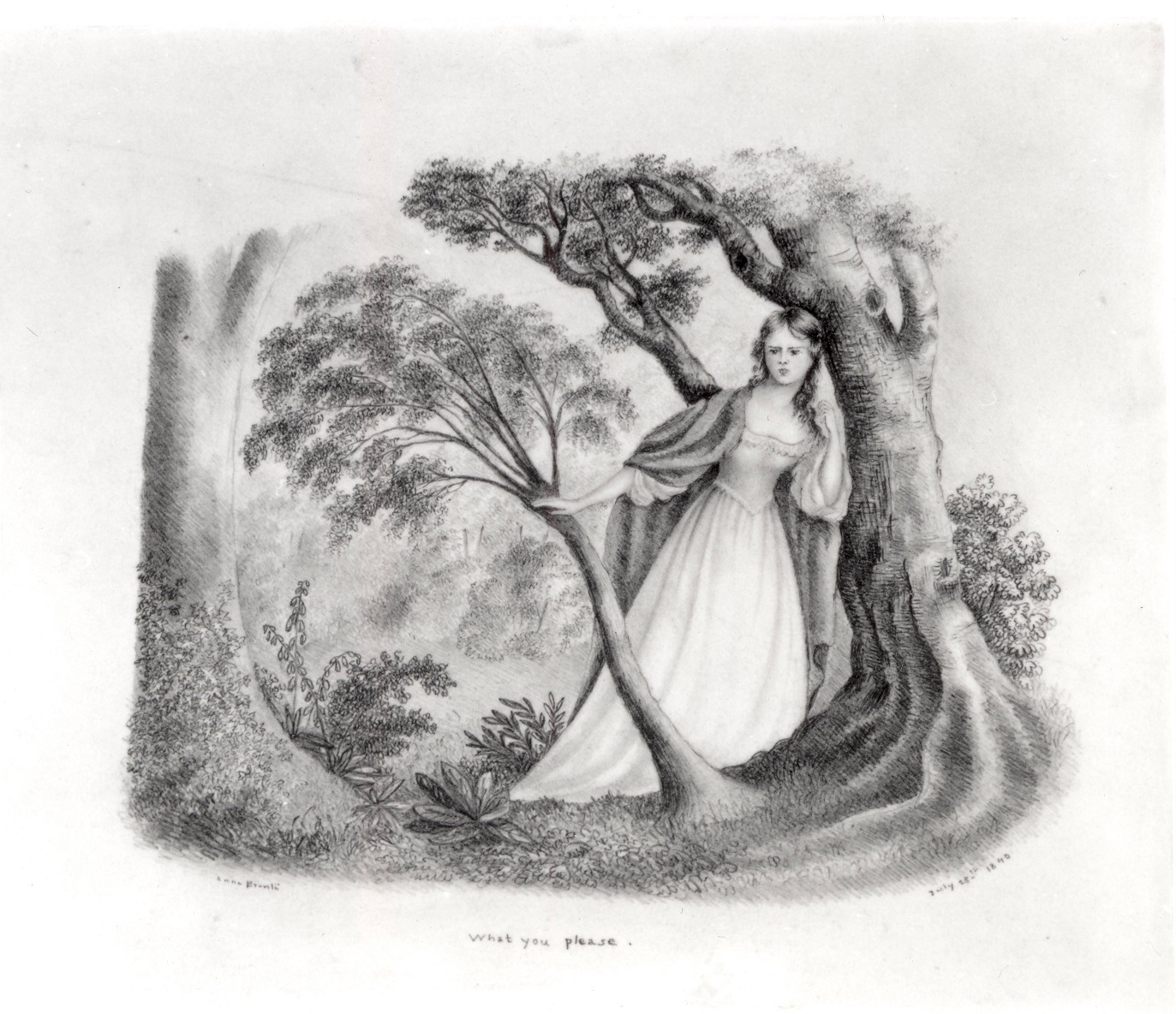

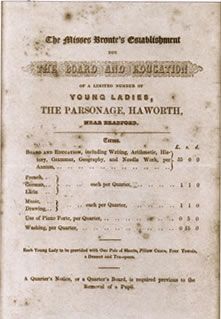

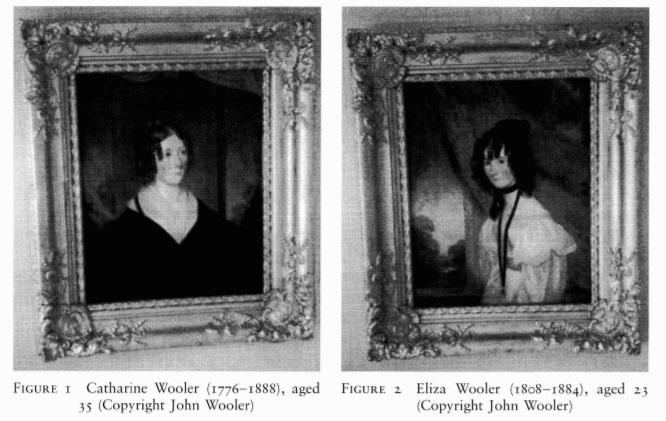

An advert in The Leeds Intelligencer newspaper on 25th January 1827 announced the impending opening of the school, and the ad instantly brings to mind the prospectuses that Charlotte later had printed for ‘The Misses’ Brontë Establishment’. Just as Charlotte had hoped to do, Margaret ran the school with her four younger sisters. The only surviving photograph of Margaret shows her in old age (you’ll see that later in the post), although we do have photographs of two sisters who were especially close to her, Eliza and Catharine. We do, however, have a couple of pen portraits of Margaret Wooler’s character, including one from Charlotte’s fellow pupil at Roe Head, Ellen Nussey. Ellen first describes how Miss Wooler allayed fears of a ghost at the top of the school (which will sound familiar to Villette fans):

‘The tradition of a lady ghost who moved about in rustling silk in the upper stories of Roe Head had a great charm for Charlotte. She was a ready listener to any girl who could relate stories of others having seen her; but on Miss W. hearing us talk of our ghost, she adopted an effective measure for putting our belief in such an existence to the test, by selecting one or other from among us to attend the stairs after the dimness of evening hours had set in, to bring something down which could easily be found. No ghost made herself visible even to the frightened imaginations of the foolish and the timid; the whitened face of apprehension soon disappeared, nerves were braced, and a general laugh soon set us all right again.’

Ellen also writes of how Margaret liked to spend leisure time with her pupils:

‘In days when out-of-door exercise was impracticable, Miss Wooler would join us in our evening hour of relaxation and converse (for which she had rare talent); her pupils used to hang about her as she walked up and down the room, delighted to listen to her, or have a chance of being nearest in the walk.’

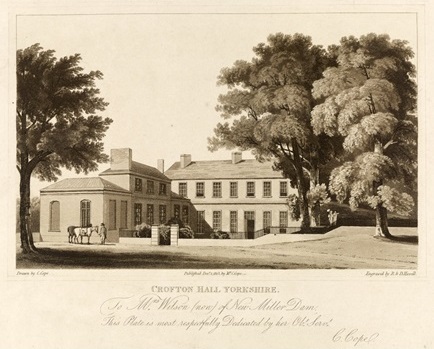

Charlotte must obviously have impressed Margaret as she invited her back to Roe Head as a teacher in 1835. During this time she also made the acquaintance of a new pupil, Anne Brontë. Again, she must have been impressed as not only did she present Anne with a medal and a book as a prize for her good conduct, it’s also safe to assume that she must have helped Anne get her first job as governess – with the leading family of Mirfield, the Inghams of Blake Hall.

Charlotte had loved life as a pupil at Roe Head, with her best friends Ellen Nussey and Mary Taylor alongside her, but she hated the drudgery of life as a teacher at the school. Anne’s near-fatal illness at Roe Head in late 1837, and her subsequent return to Haworth, proved the catalyst for Charlotte to let off steam – in the direction of her employer. We can imagine how volcanic Charlotte’s eruption was, as she wrote to Ellen to explain the head to head she’d had with Margaret:

‘We came to a little eclaircissement one evening – I told her one or two plain truths which set her a-crying, and the next day unknown to me she wrote to Papa telling him that I had reproached her bitterly, taken her severely to task etc. etc.’

Charlotte resolved to leave her school. It says a lot for Margaret’s character and kindness that she instead persuaded Charlotte to continue as a teacher:

‘Just before I went away she took me into her room and giving way to her feelings which in general she restrains far too rigidly, gave me to understand that in spite of her cold repulsive manners she had a considerable regard for me and would be very sorry to part with me – if anybody likes me I can’t help liking them, and remembering that she had in general been very kind to me I gave in and said I would come back if she wished me. So, we’re settled again for the moment, but I’m not satisfied, I should have respected her far more if she had turned me out of doors instead of crying for two days and two nights together.’

Eventually Charlotte did leave the school, and given the reproaches that Charlotte had given her we could have expected that to be the last Margaret saw of her – but in fact, as we shall see, they become firm friends.

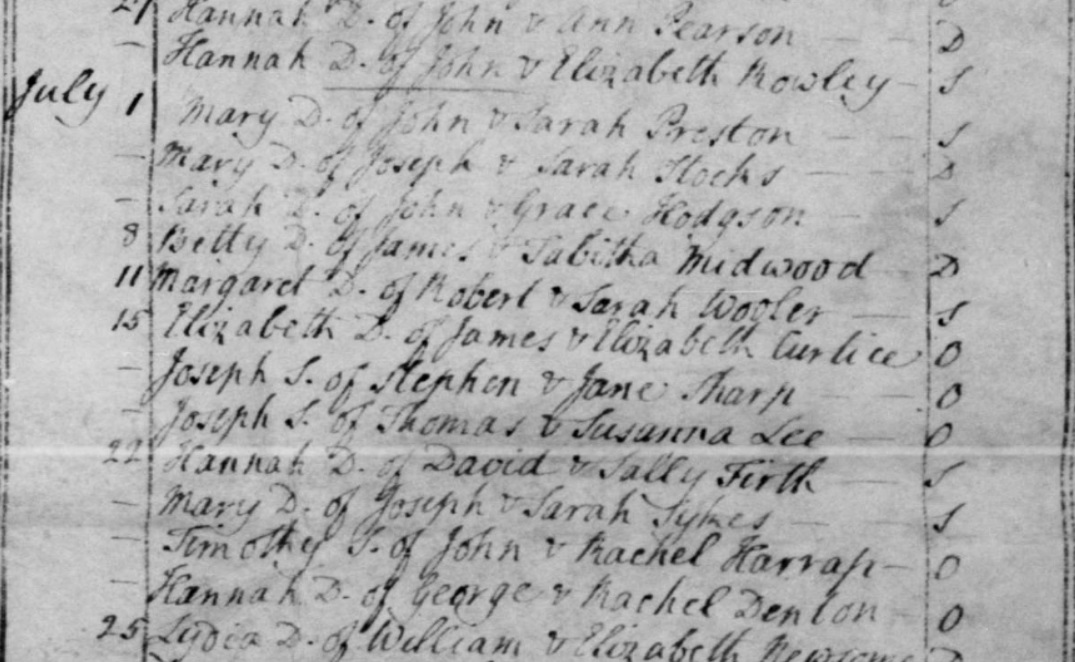

Firstly, let’s look at what else we know about Margaret. When you want to research a person from the nineteenth century, it always makes sense to look at genealogy records first – so that’s what I did with Margaret. Here is the record of her baptism on 11th July, 1872 – can you see her?

Margaret was born on 10th June 1792 to Robert and Sarah Wooler. Her father was a mill owner, and the family were wealthy. We next encounter a Margaret Wooler in rather surprising circumstances in 1811. On 29th April of that year, in Mirfield parish church a Margaret Wooler married a Michael Holcar. Could this be our Miss Wooler of Mirfield, and if so why was she not Mrs Holcar? My first thought was that she was in fact a widow, but if so why did she revert to her maiden name? Could it be another Margaret Wooler in Mirfield? Alas, we will never know, as try as I might I could find no more details of this married couple – in fact, rather surprisingly once again, I can find no other record at all of a Michael Holcar living anywhere in England at this time. It will have to remain a mystery.

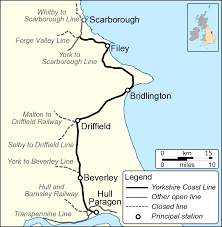

After our Miss Wooler retired from teaching she offered Charlotte the lease of her own school, by then in Dewsbury, on condition that she could continue to live there too, but Charlotte chose instead to head to Brussels to further her education. In her retirement, Margaret bought and lived in a number of properties, including one at the North Bay of Scarborough. Hearing from Charlotte that Anne Brontë was desperately ill in 1849, and that she wanted to see Scarborough one last time, she offered the sisters the use of her home free of charge. Anne decided that she wanted to stay on her favourite South Bay instead but it is clear that Margaret heard of Anne’s death on 28th May, either from Charlotte or Ellen, or in the local newspaper, as she too attended the funeral service at Christchurch – paying her last regards to one former pupil, and providing support to another.

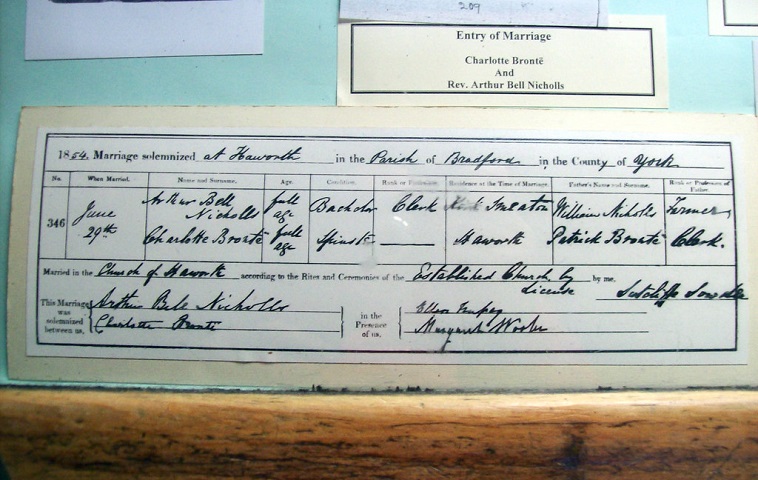

By looking at census returns we see that in 1851 Margaret was living in Dewsbury once more, this time in Dewsbury Parsonage with her sister Susanna and her brother in law the Reverend Edward Nichols Carter. Three years later she was called upon to provide a very important service to Charlotte Brontë. Just as Anne’s funeral had been, Charlotte’s wedding to Arthur Bell Nicholls in 1854 was a very private and low-key affair. We know from a first hand account of the service that there were only eight people present, including the happy couple, and we have Margaret’s signature on Charlotte’s wedding certificate. She had been invited to serve as a bridesmaid with Ellen Nussey, but at the last moment Patrick had decided he was too ill to attend and so Miss Wooler stepped up to assume the father of the bride role, and gave Charlotte away. I doubt that Charlotte could have envisaged that happening on that day 17 years earlier when she had given Margaret a piece of her mind.

Margaret’s travelling days weren’t over – the 1861 census shows that she had returned to the east coast, and was residing at Newbegin boarding house, Hornsea (the town now famous for its pottery, including a Brontë range) with a Margaret Warner. In 1871 Margaret was living with Susanna and Reverend Carter again, this time at the delightfully named Strawberry Square in Heckmondwike, Yorkshire.

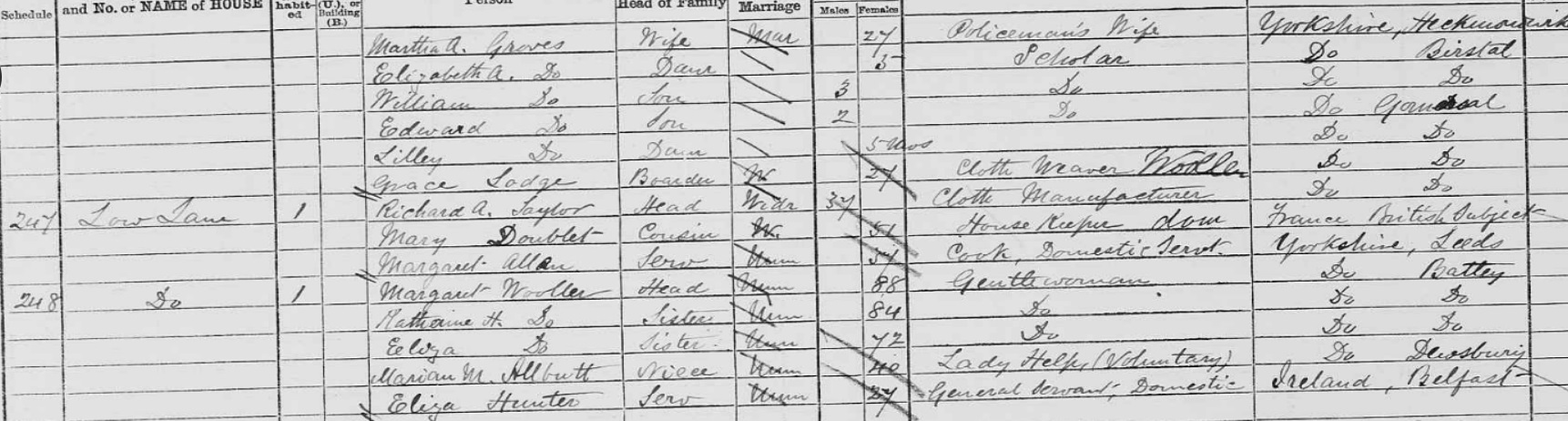

The 1881 census shows us that Margaret is now a the head of the household at 248 Low Lane, Gomersal. By then nearing ninety years of age, she is living with two servants and, rather touchingly, her two sisters mentioned earlier – Catharine (misspelt Katharine on the form) and Eliza, aged 84 and 72 respectively. We have three sisters living together, but not the Brontës, the Woolers. This house in Gomersal was a short walk from where two of her former pupils were living at the time, Ellen Nussey and Mary Taylor, and I like to think they visited her on occasions and talked about the old days with Charlotte.

Certainly, Margaret had plenty of opportunity to talk about the Brontës, for in her final years she found herself much in demand. We know this from a moving account of Margaret given in 1952 by one who still remembered her. Longevity obviously ran in the genes, for the interview was given by 91 year old Reverend Max Blakeley, the grandson of Margaret’s sister Susanna. This is the second of the pen portraits I mentioned, so let’s see what Max had to say:

‘Margaret Wooler, Charlotte Brontë’s teacher and friend, was my grandfather’s sister. To me she was always “Aunt Wooler”… My earliest recollections of Aunt Wooler and her sisters, Catharine and Eliza, take me to the time when I was about eight years old. I lived at Heaton Lodge Park, near Dewsbury, and they lived in West House, Dewsbury, in a wing of their brother’s house. I was taken by my governess to see them, and as I had up to that time only met Aunt Eliza, who, though I later discovered her to be kind, was rather austere and “proper”, I felt nervous. The thought of facing three ladies of the same sort was something of an ordeal to a small boy. I saw the three aunts all sitting together and soon, child though I was, I realised that they were all very different characters. On the table between them was a large dish of oranges. Aunt Wooler, who saw me looking at them longingly, said “Would you like an orange?” Aunt Catharine gave a chuckle. Aunt Wooler then said, “would you like an orange, or that paper knife?” I well knew which, but dare not say anything with Aunt Eliza’s seemigly stern eye upon me, but she said quickly, “Oh, of course, the paper knife. But wait till you are grown up.” Feeling in doubt I looked at each Aunt in turn, and it was Aunt Wooler who, with a kind smile, held out an orange for me. This may seem a trivial thing to remember, but it has always typified for me the kind of person she was. She was not a martinet, as some people have thought…

Late in her life reporters often went to see Aunt Wooler, and when she was over ninety and not really fit for it she was constantly being visited by Americans who came with the sole purpose of interviewing her about Charlotte and the Brontës. She said to me, “I cannot refuse to see them. It was very trying, but I will do my best.”’

Margaret Wooler always did her best for the Brontës, she was always there unconditionally when needed. The 1881 census lists her as a ‘gentlewoman’, and that’s exactly what she was – gentle and kind. She passed away in Gomersal on June 3rd, 1885 aged 92. She is buried in Birstall churchyard, near to a woman she had spent many pivotal moments with: Ellen Nussey. Even in death, you can’t keep Margaret Wooler far away from the Brontë story.