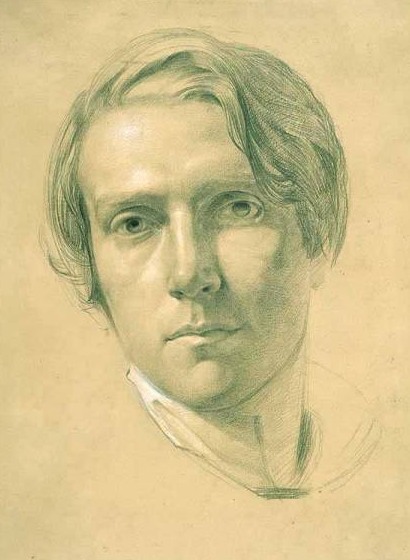

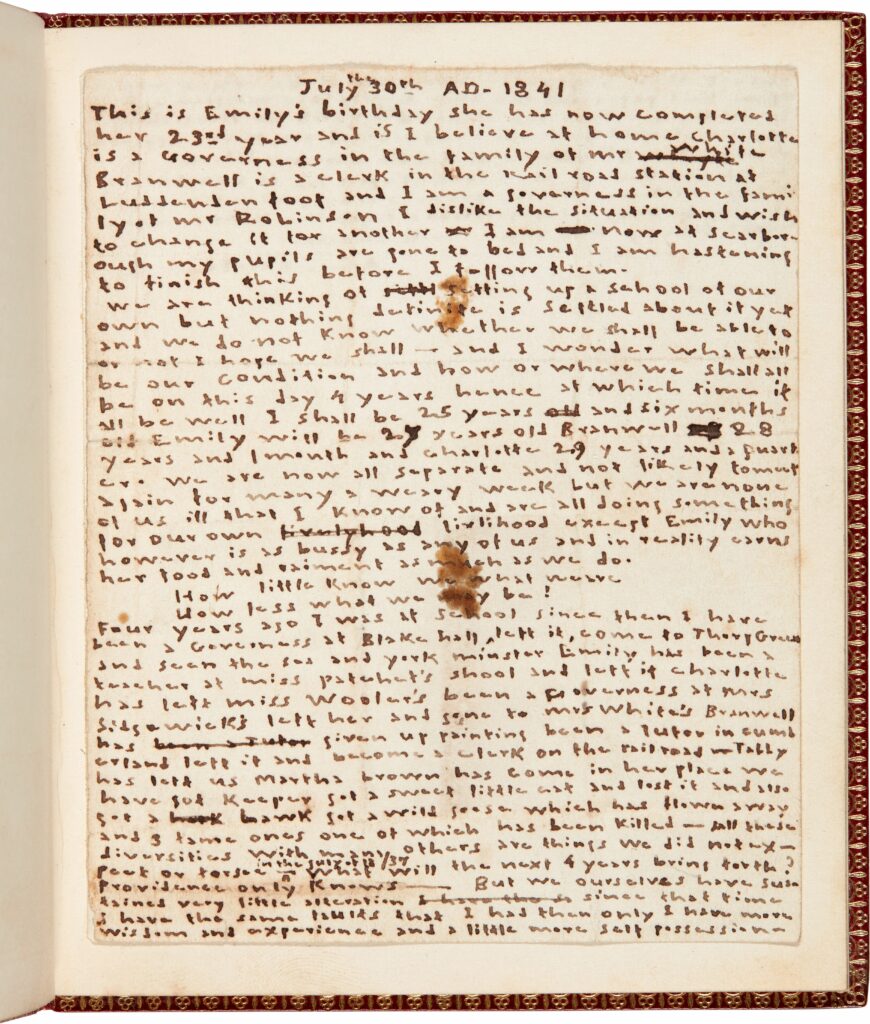

This weekend marks the 204th anniversary of Patrick Branwell Brontë, born in Thornton, Bradford on 26th June 1817. Okay, it’s a day after the day itself, but we’re sure that Branwell would still be celebrating.

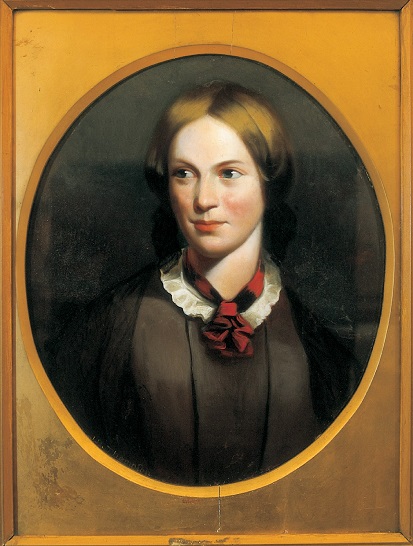

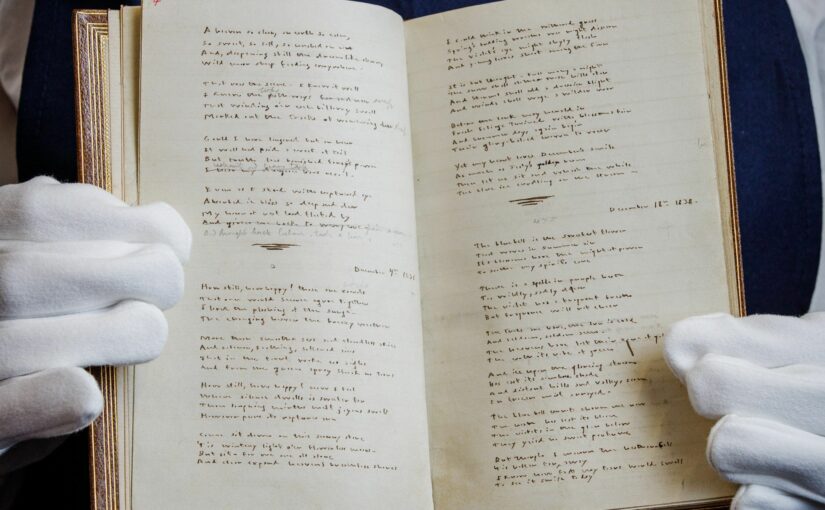

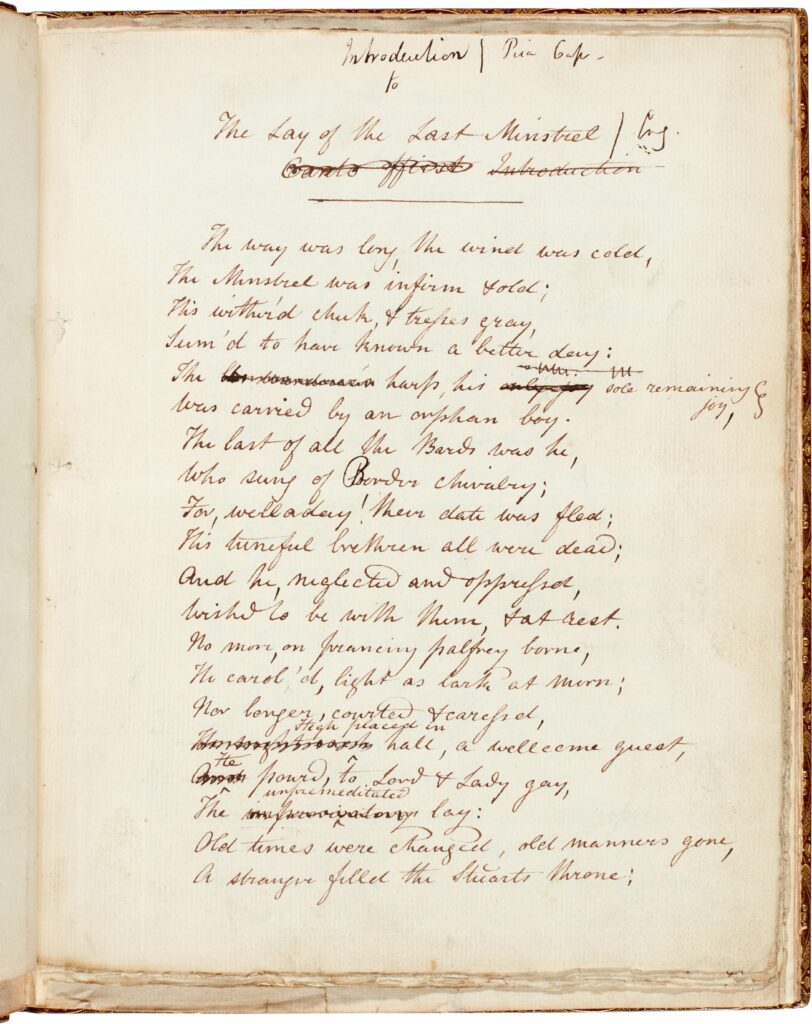

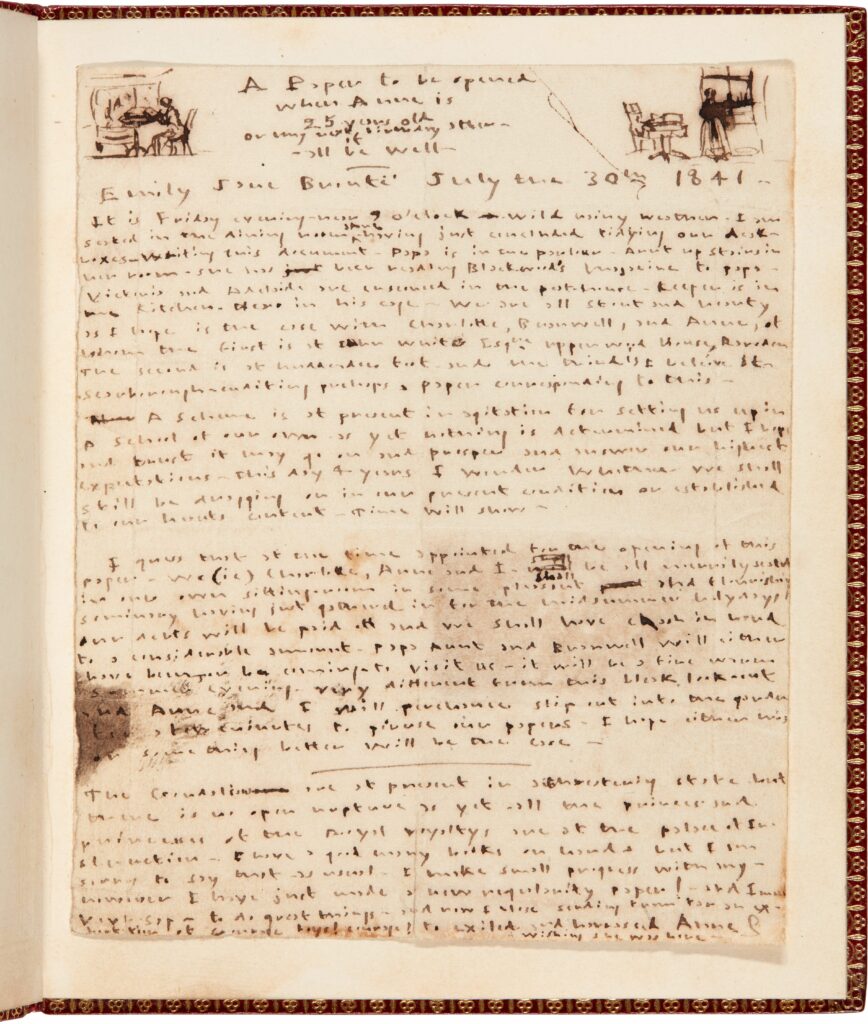

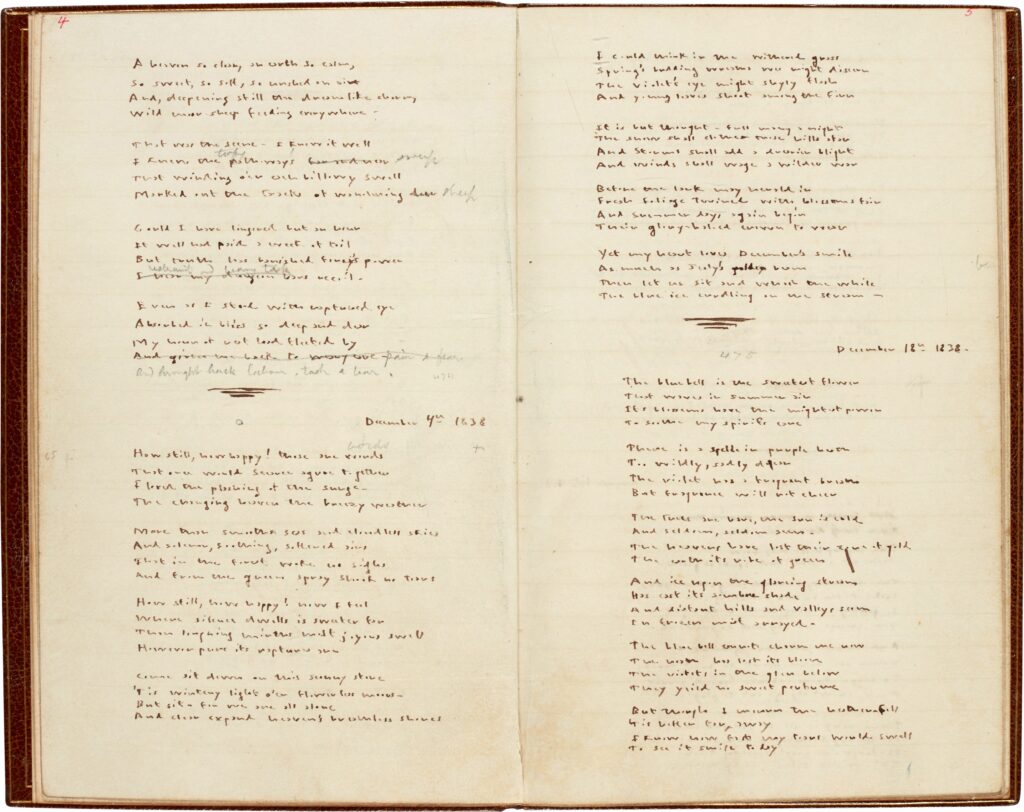

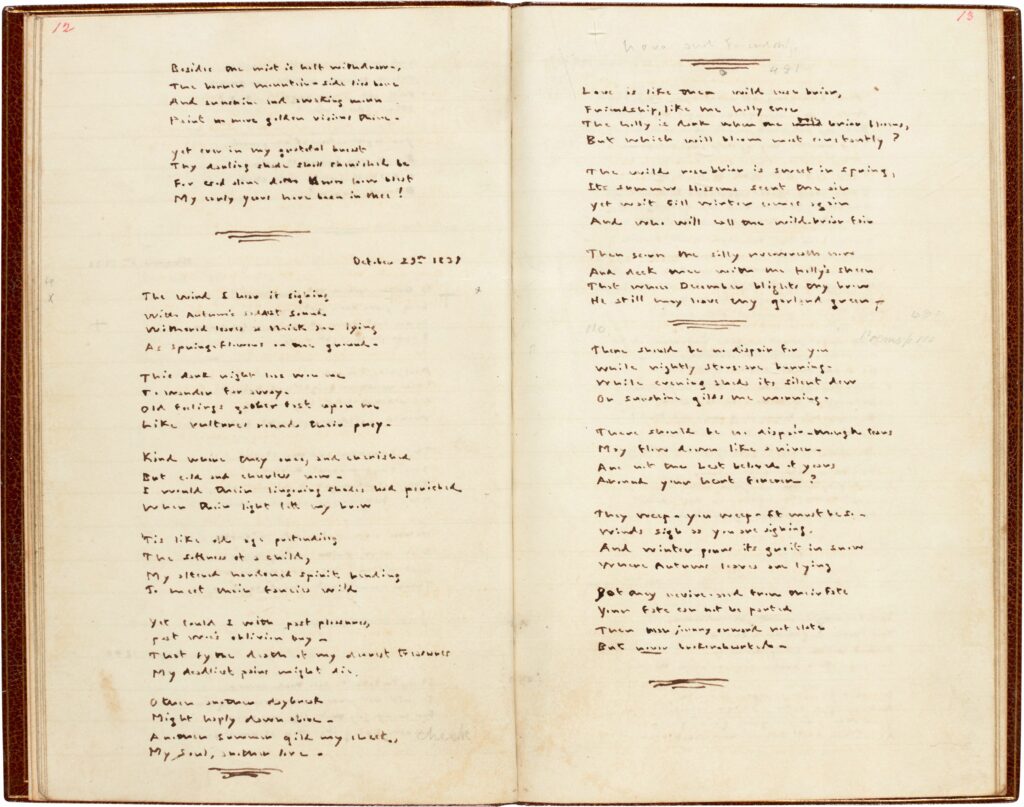

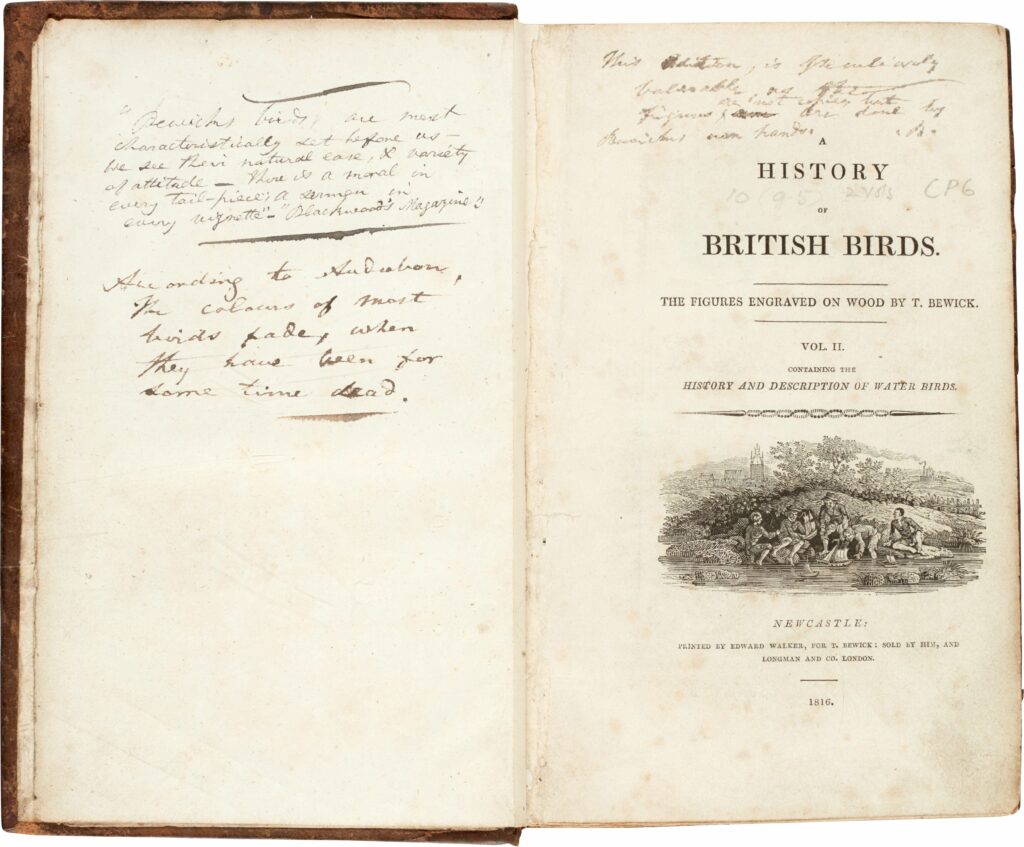

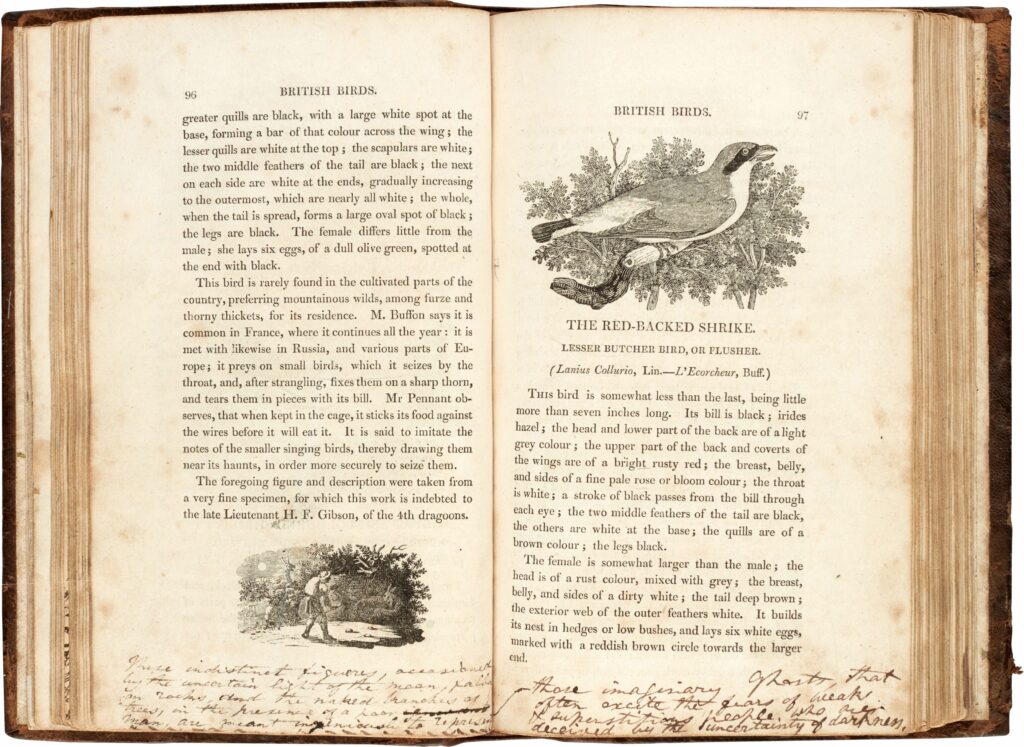

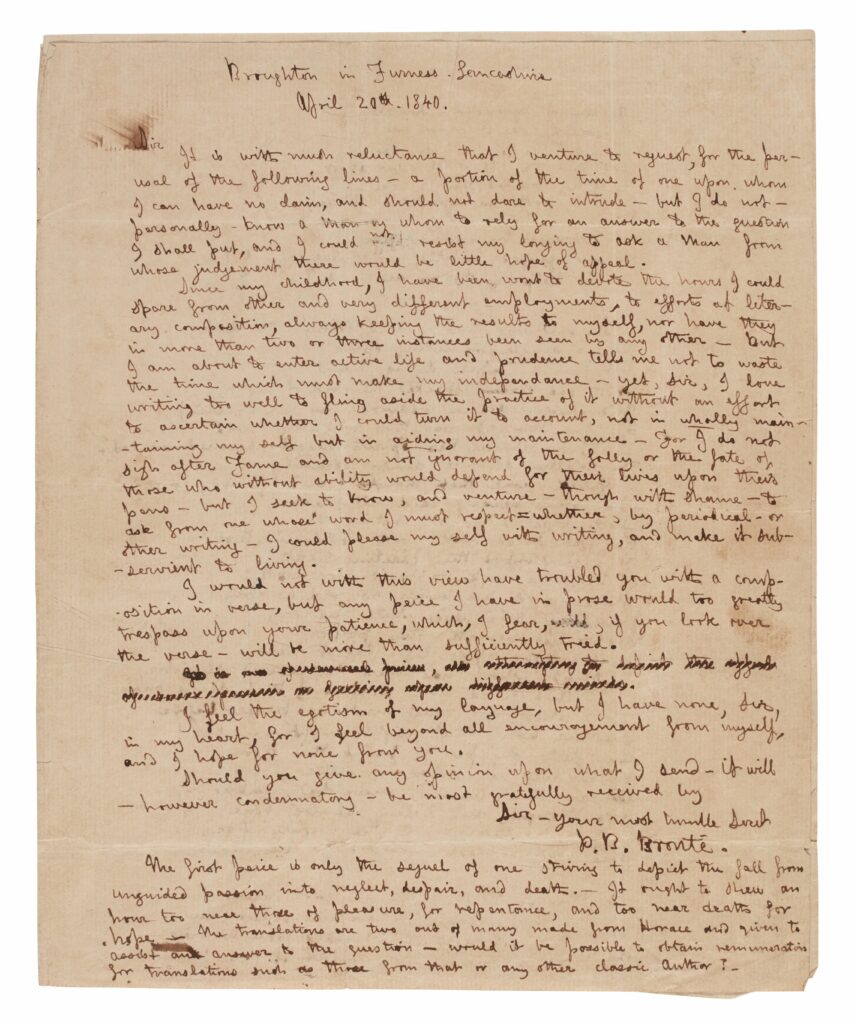

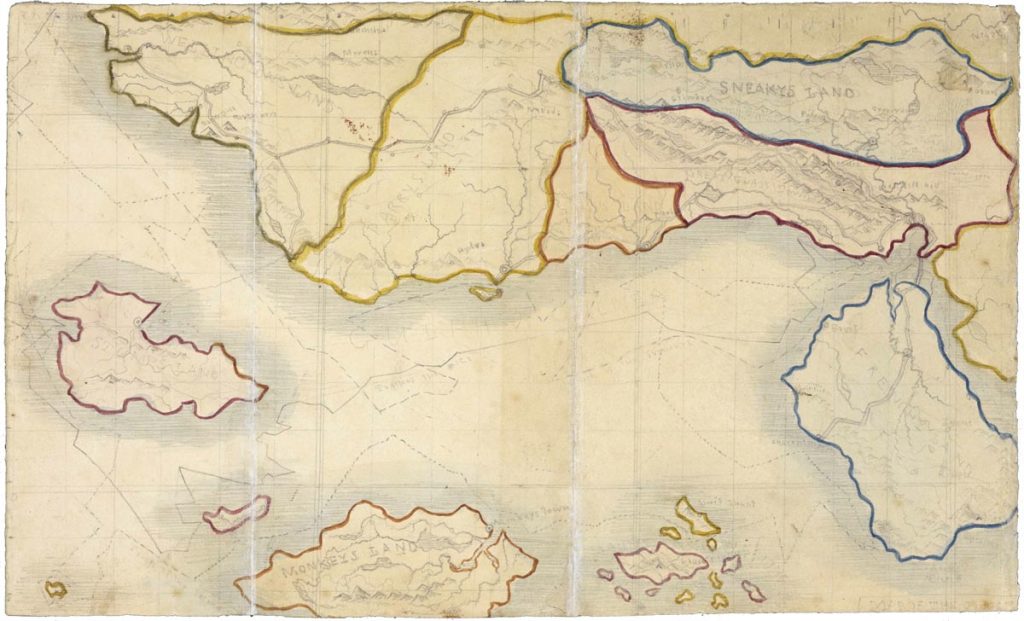

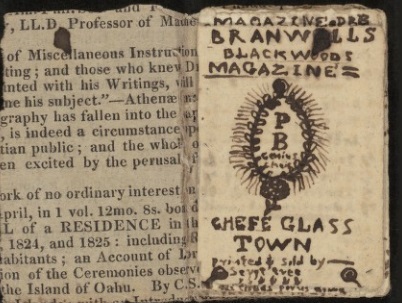

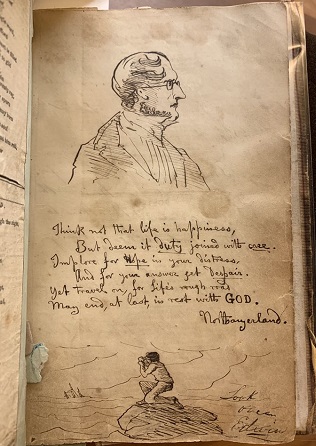

What do we know about Branwell Brontë? He was the fourth of six Brontë siblings, born a year and two months after Charlotte Brontë. He and Charlotte were particularly close in childhood, and it was they who led the way into the kingdoms of Glass Town and Angria, leading to an explosion of youthful creativity and the little books which we can still see at Haworth Parsonage Museum today.

He was a man who found life a challenge, who was hit hard by the childhood losses of his mother and two eldest sisters, and then by failures in his artistic and literary dreams, and in love. Somehow, Branwell has taken on a Byronic twist for many, he is seen as ‘mad, bad, and dangerous to know’ but is that a true and complete picture? I don’t think so, and nor did the people who knew him. In today’s post we’re going to delve into the archives and look at first person encounters with Branwell Brontë!

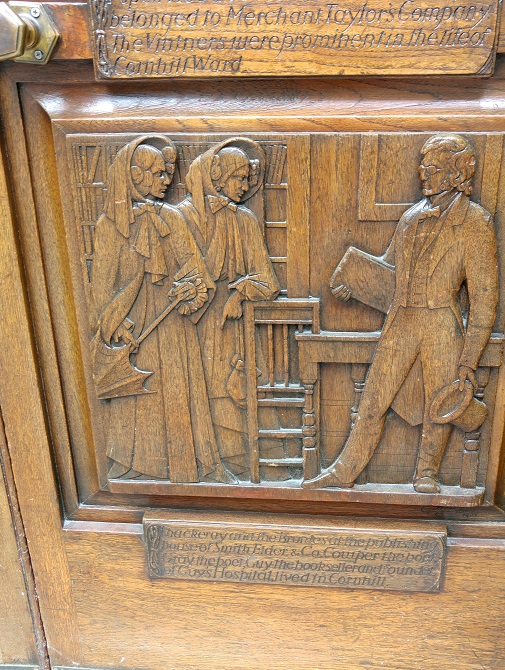

Chamber’s Journal, 22 February 1868

‘To his mind, Mr Branwell was the cleverest of the family. A wonderful talker he was, and able to do things which nobody he had ever seen could do. He had seen Branwell sitting in the vestry, talking to his father, and writing two different letters at the same time. He could take a pen in each hand, and write a letter with each at once. He had seen him do that many times, and had afterwards read the letters written in that way. Yes; it was true that he had come to a sad end, but Mrs Gaskell had not stated the case about him correctly. Haworth people did not like Mrs Gaskell at all. There was a deal of feeling against her for what she had said about Mr Branwell, and the villagers encouraging him to drink. Mrs Gaskell said that he had learned to drink as a boy, and had gone on strengthening his habit; but that was not true. When he was nineteen years old he was secretary to the temperance society in the village, and it was not until after that that he learned to drink. It was not correct that the landlord of the Bull had anything to do with teaching him, though it was quite true that he used to sit in the back parlour there and drink almost constantly of an evening when he was older. But if he could not have got drink there, he would have been sure to have got it somewhere else. But, oh, he was a fine talker Branwell; and such a talker! Ay, and when he was at the worst, he never missed coming to the Sunday school with his sisters. They all used to come regularly.’

Francis Leyland, Leeds Times, 28 July 1883

‘Although the biographers of the Brontë family have done their best to destroy the reputation of Branwell for any mental gifts or manly virtues he might at any time have had, there was a better side of his nature, with which the readers of Brontë literature are unacquainted, but which they may know ere long. There can be no doubt that the irregularities of Branwell’s young life clashed with the formal manners of the parsonage. It is not surprising that Miss Brontë, in correspondence with a friend, should inform her of the apprehensions she felt respecting her brother. It is certain that Miss Brontë never intended the private concerns of the parsonage to be made known to others. Mr Brontë expressed to me his sorrow that his son’s irregularities were made known to the world. That Branwell was miserable I admit; but I deny that his misery was caused by drink, although he sometimes – and towards the close of his life too often – sought oblivion from his own woes in society and indulgence. Yet he was too worthy a member, on many accounts, of the Brontë family to be excluded from it as entirely worthless, reprobate, and lost. I speak from personal knowledge of him, I possess many of his writings in letters and poems, and I hope at no distant day to demonstrate his power, and to dispose of many of the calumnies with which a hasty and ill-considered judgment has overshadowed his memory.’

Nancy de Garrs, Pall Mall Gazette, 12 December 1884

‘“Branwell was a good lad enough,” she says, “until the serpent beguiled him,” and she thinks he has been “made out to be a good deal worse than he really was.” Nancy could “manage him” better than any one else when his fits of fury were upon him, and Branwell seemed to have a real affection for his old nurse. He often wanted to paint her portrait, but she declined on the score that she did not consider herself good looking enough.’

J. S. Horsfall, Leeds Mercury, 15 September 1897

‘My most vivid remembrances are of Branwell Brontë, who was a great friend of my father’s, and whom I distinctly remember one evening at our house reciting from ‘Childe Harold,’ Byron’s fine address to the ocean. I never forgot it. It made a great impression on my mind, and I can remember him now, a little man (compared with my father, who was tall) with light, reddish hair, and wearing spectacles.’

Charles Hall, Sheffield Daily Telegraph, 7 February 1908

‘Branwell died in my childhood, but one heard a good many stories about his appearances at the ‘Black Bull’. He was a merry, well read, interesting boy, and it was not surprising that the men who gathered at the ‘Black Bull’ for liquor and entertainment enjoyed his gay company and made him welcome; nor was it surprising that he went there, considering that there was not a lad in the village, of his own social standing, with whom he could have consorted. It was a pity he was not sent away in early life, then all might have been different.’

Batley Reporter and Guardian, 30 June 1877

‘The room in which this lively scene occurs has no doubt witnessed many still more lively, for it was the sanctum sanctorum of the company that gathered round Branwell Brontë while he kept the table in a roar with his lively sallies of wit, or astonished and dazzled the more intelligent portion of his friends by his eloquent and thoughtful discourse. There in the corner is “Mr. Branwell’s chair,” old and curious enough to be placed in some museum, and there he would sit with his “great tawny mane” dishevelled, and his bright eyes turned to the ceiling, talking most eloquently to the admiring villagers, with whom anyone who visits Haworth will soon find he was a firm favourite. Poor Branwell! What a pity that a life of such promise should have been so cruelly wasted. Every elderly man you meet knew Branwell. Charlotte and her sisters they were also familiar with, but they were very reserved, and kept apart. Branwell, however, was free and open. They will all give you anecdotes of him.”

Francis Grundy, Pictures Of The Past: Memories of Men I Have Met And Places I Have Seen

‘Soon after I came to Halifax, I made the acquaintance of a genius of the highest order, Patrick Branwell Bronte, who was at least as talented as any member of that wonderful family. Much my senior, Bronte took an unusual fancy to me, and I continued, perhaps, his most confidential friend through good and ill until his death. Poor, brilliant, gay, moody, moping, wildly excitable, miserable Bronte! No history records your many struggles after the good, – your wit, brilliance, attractiveness, eagerness for excitement, – all the qualities which made you such ‘good company,’ and dragged you down to an untimely grave. But you have had a most unnecessary scandal heaped upon you by the author of your sister’s Biography by which that scandal does its best to spoil.

This generous gentleman in all his ideas, this madman in many of his acts died at twenty-eight of grief for a woman. But at twenty-two, what a splendid specimen of brain power running wild he was! what glorious talent he had still to waste! That Rector of Haworth little knew how to bring up and bring out his clever family, and the boy least of all. He was a hard, matter-of-fact man. So the girls worked their own way to fame and death, the boy to death only! I knew them all.

The father, – upright, handsome, distantly courteous, white-haired, tall ; knowing me as his son’s friend, he would treat me in the Grandisonian fashion, coming himself down to the little inn to invite me, a boy, up to his house, where I would be coldly uncomfortable until I could escape with Patrick Branwell to the moors…

Branwell was very like them [Charlotte, Emily and Anne], almost insignificantly small – one of his life’s trials. He had a mass of red hair, which he wore brushed high off his forehead, – to help his height, I fancy ; a great, bumpy, intellectual forehead, nearly half the size of the whole facial contour ; small ferrety eyes, deep sunk, and still further hidden by the never removed spectacles ; prominent nose, but weak lower features. He had a downcast look, which never varied, save for a rapid momentary glance at long intervals. Small and thin of person, he was the reverse of attractive at first sight.

This plain specimen of humanity, who died unhonoured, might have made the world of literature and art ring with the name of which he was so proud…

He would discourse with wondrous knowledge upon subjects, moral, intellectual, philosophical, for hours, and afterwards accompany his audience to the nearest public-house, and recruit his exhausted powers by copious libations. He was proud of his name, his strength, and his abilities. In his fits of passion I have seen him drive his doubled fist through the panel of a door: it seemed to soothe him; it certainly bruised his knuckles. At times we would drive over in a gig to Haworth (twelve miles), and visit his people. He was then at his best, and would be eloquent and amusing, although sometimes he would burst into tears when returning, and swear that he meant to amend. I believe, however, that he was half mad, and could not control himself…

Poor fellow! this short story by a weak hand is all the biography his memory will know. His age was twenty-eight. I have always been of opinion that it remained for me to clear his name from the weight of accusation heaped upon it. I knew him, and indeed, I believe, all the family, better than Mrs. Gaskell did. He was a dear old friend, who from the rich storehouse of his knowledge taught me much. I make my humble effort to do my duty to his memory. His letters to me revealed more of his soul’s struggles than probably was known to any other. Patrick Branwell Bronte was no domestic demon – he was just a man moving in a mist, who lost his way. More sinned against, mayhap, than sinning, at least he proved the reality of his sorrows.’

A man moving in a mist indeed, but with the passage of time those mists clear. We can now see that Branwell Brontë was a talented man, a kind hearted man, but one who needed help that simply wasn’t available at that time. Nevertheless, we can say, ‘Happy 204th birthday Branwell Brontë.’

I leave you now with exciting news of a new Brontë documentary being shown next week! ‘Brontë’s Britain with Gyles Brandreth‘ is being broadcast here in the UK on Channel 5 at 9pm on Tuesday, 29th June (after the England match is over, so there’s no excuse not to watch). It should be both entertaining and informative, especially as Gyles is a passionate fan of literature and the Brontës himself. I hope you enjoy it, and I hope to see you next Sunday for another new Brontë blog post.