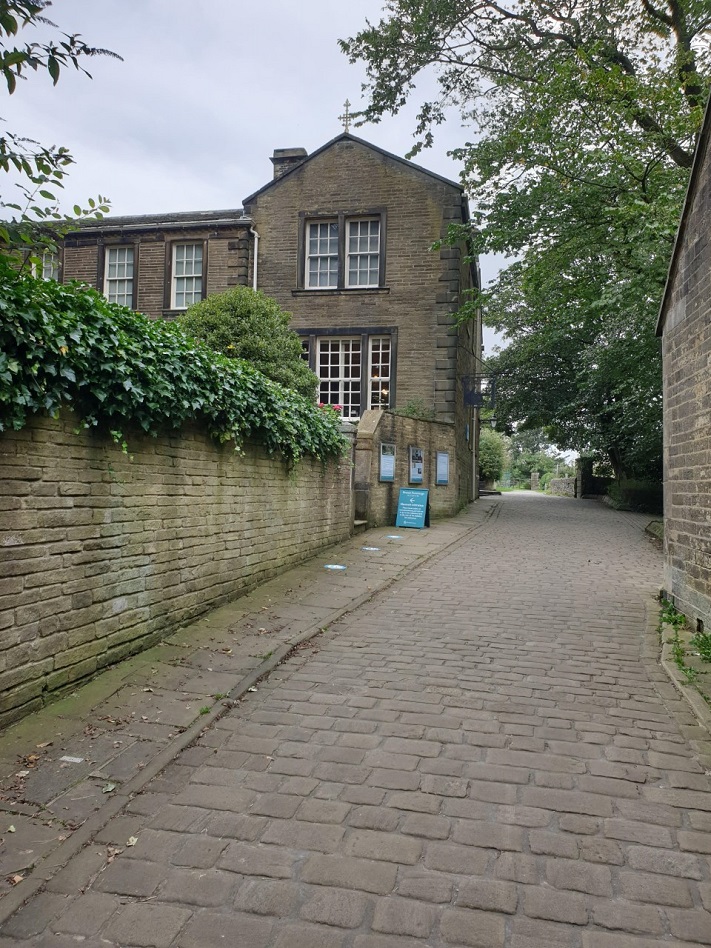

As I type this I’ve just returned from my favourite place on earth: Haworth, home of the Brontës (you’ll see some of the pictures I took scattered throughout this post). It’s nearly eight months since I was last there, but that octet of months has been unlike any other. Our world has changed, and some things about Haworth have changed, but I’m pleased to report that it still retains its beauty and its unique atmosphere. It might be a little quieter, there may be more social distancing, but visitors can still walk in the footsteps of the Brontës. We can follow their footsteps to the parsonage, to the church and the old school rooms, and to shops such as the old apothecary they knew, and it’s this latter shop that I’m going to look at today.

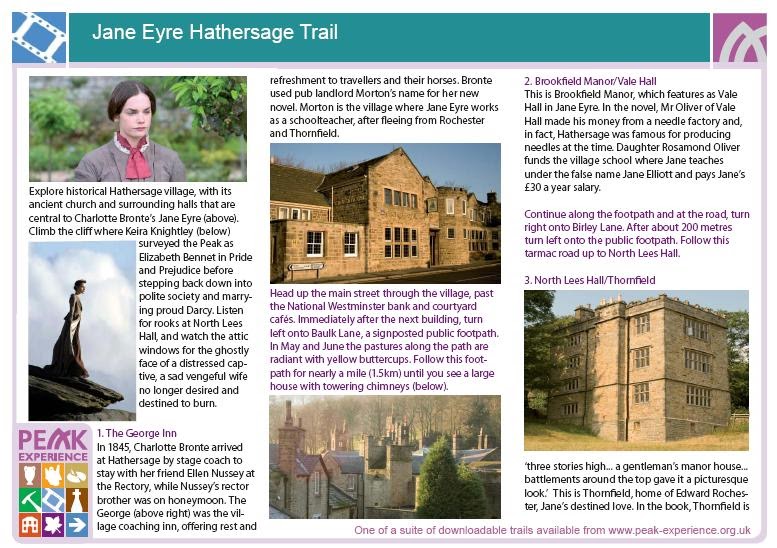

The old apothecary shop is situated at the top of Main Street, opposite the Brontë church of St. Michael and All Angels. It has undergone a number of transformations and name changes since the mid-nineteenth century, and today it is known as The Cabinet Of Curiosities. It really is a must see shop for visitors to Haworth, and inside you’ll find a wide variety of unique and fabulous items, from replica phrenology skulls and witchy items to hand crafted wax melts, bath salts and toiletries.

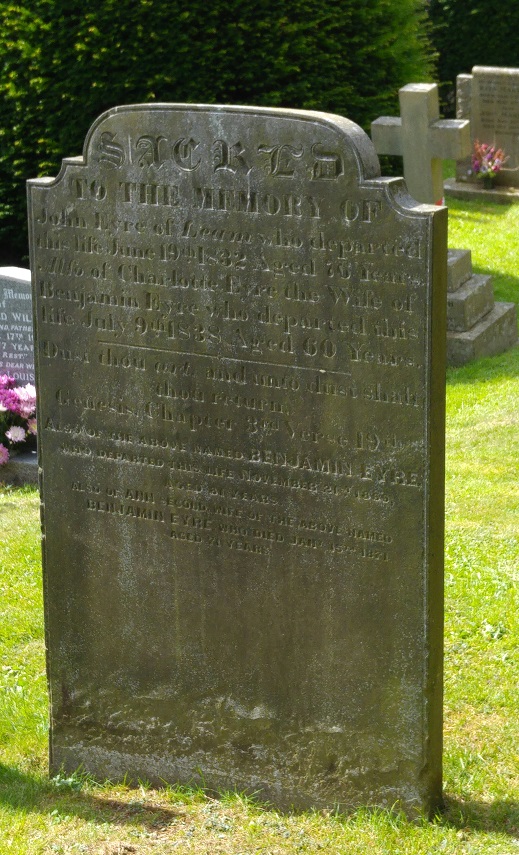

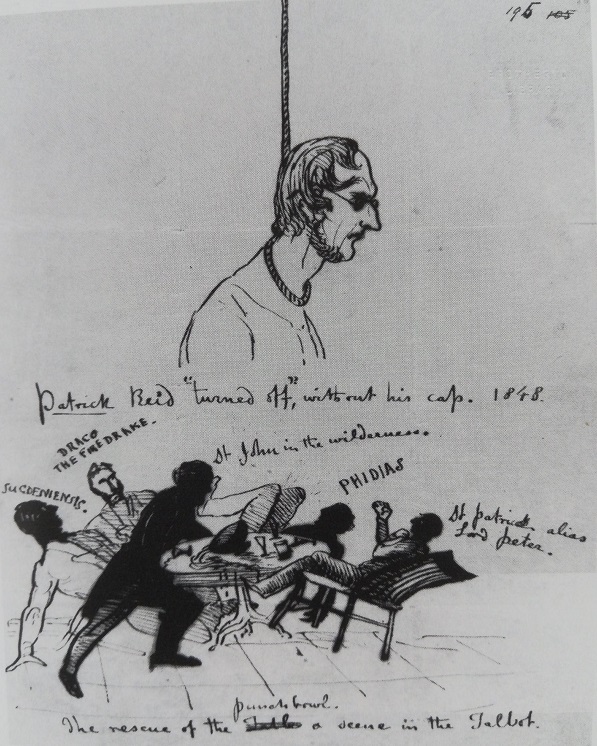

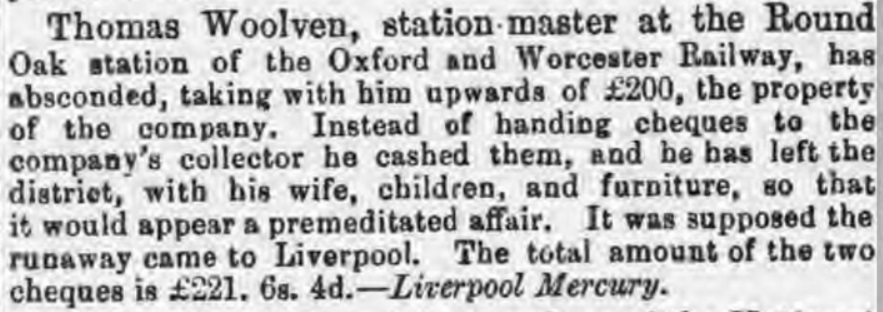

It is a shop at once both ancient and modern, and one which still proudly displays its Brontë heritage thanks to a long-standing plaque outside which reads: ‘When the Brontë family lived in Haworth this was the druggist’s house and shop. The pharmacist at the time was Bessy Hardacre & it was she who dispensed laudenum [sic], an opium derived drug, to Branwell Brontë in the years leading up to his death in September 1848, aged 31.’

For decades this sign has proudly proclaimed Betty Hardacre as the woman who ran the apothecary (an old name for a chemist’s or pharmacist’s shop) in Haworth. It is this woman whom Elizabeth Gaskell, in her biography of Charlotte Brontë, referred to as ‘s good neighbour of the Brontës – a clever, intelligent Yorkshire woman, who keeps a druggist’s shop in Haworth, and from her occupation, her experience, and excellent sense, holds the position of village doctress and nurse, and, as such, has been a friend, in many a time of trial, and sickness, and death, in the households round.’

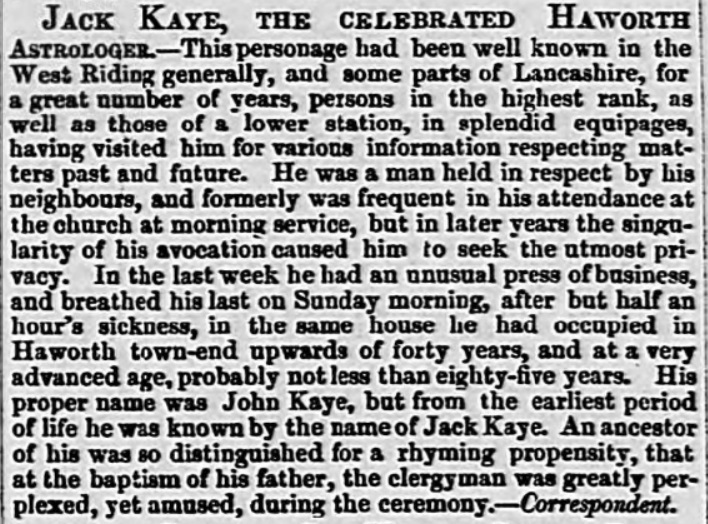

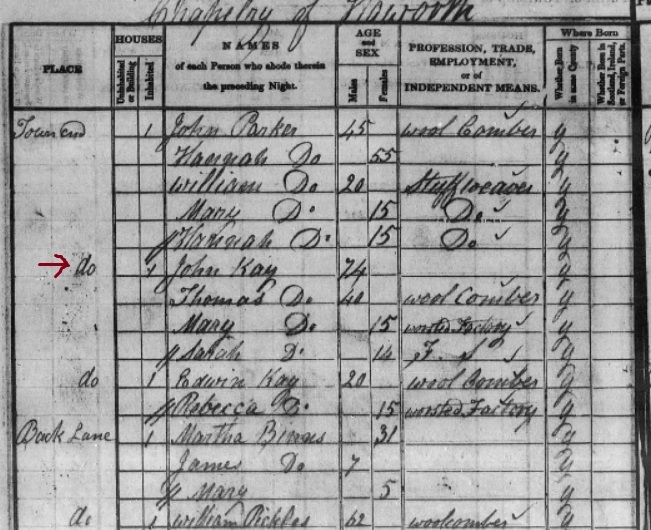

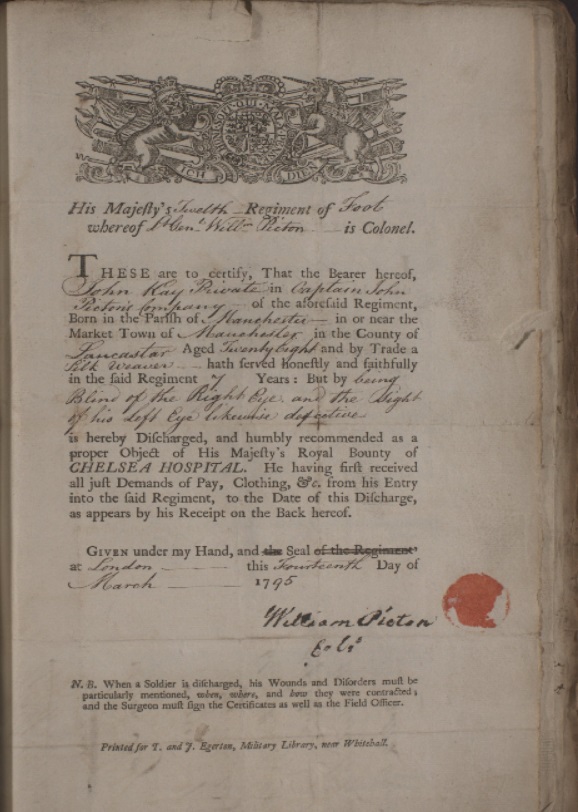

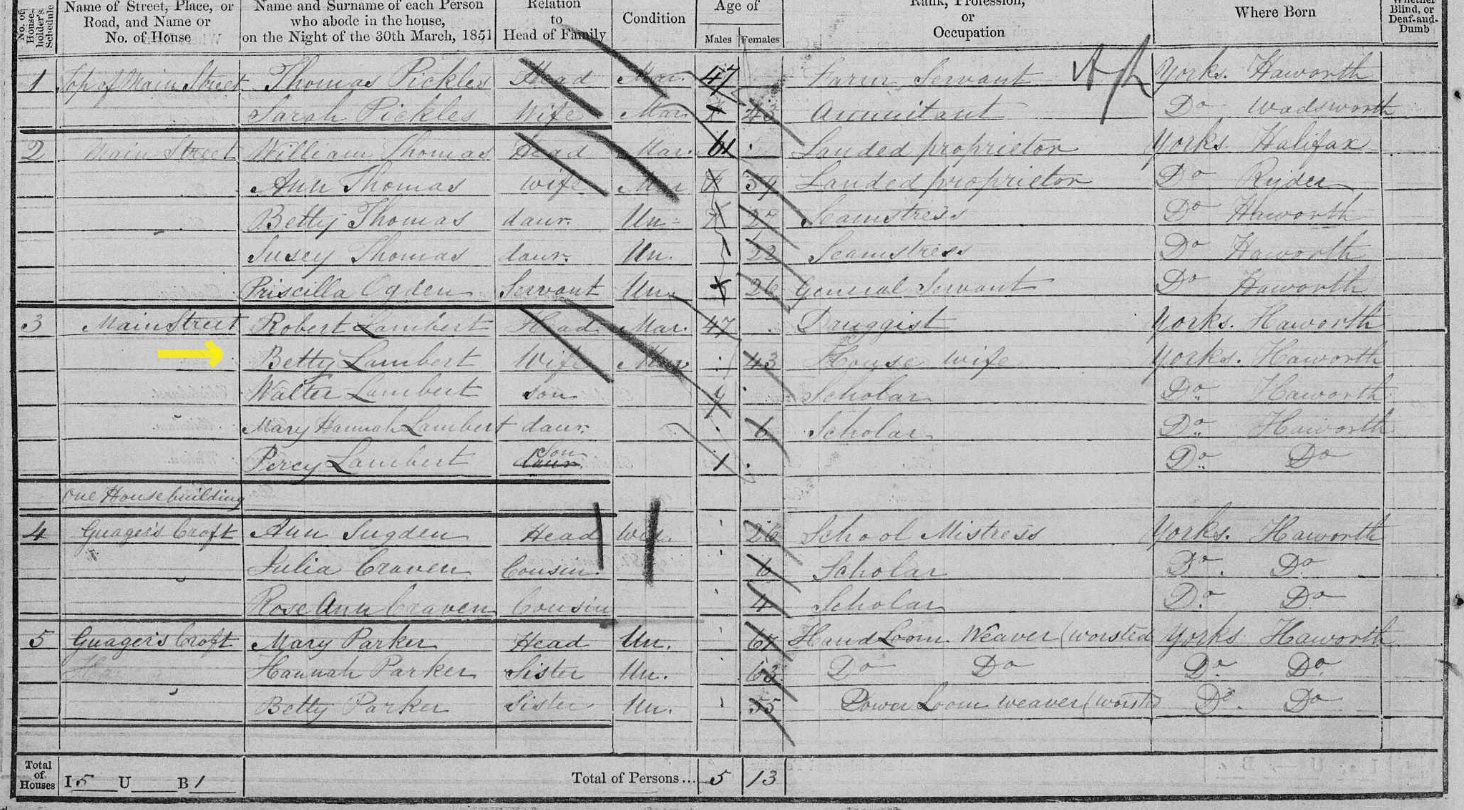

In other books on the Brontës we find this woman referred to as Betty Hardaker. We find that she was a woman who was very respected in Haworth society, and yet her wares were instrumental in the downfall and death of Branwell Brontë. Thanks to the sign and the books, Betty Hardacre the apothecary has gone down in Haworth history, but in fact the story is completely wrong. I always advise would be biographers to delve into genealogy records and newspaper archives as a main primary source, and once again they’re very revealing. Betty Hardaker is not the apothecary living at the top of Main Street, but a woolcomber and farmer’s wife living outside of the village itself. As the census records for 1841, 1851 and 1861 show, the actual apothecary, or druggist, for Haworth was Robert Lambert, who ran his Main Street store with the help of his wife Betty. It seems then that over time the names of the two Bettys have become mixed up; the name on the plaque should be that of Robert Lambert, and it was Betty Lambert who acted as village nurse and as a confidante to Elizabeth Gaskell.

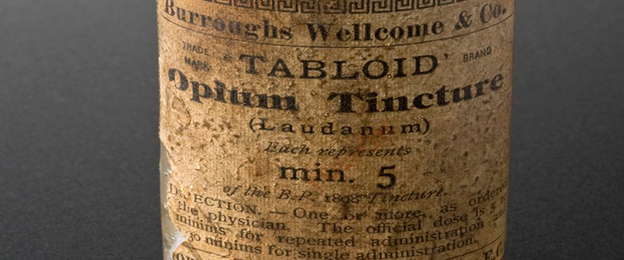

Just what did the Lamberts prescribe in their old apothecary shop? Medical knowledge came on leaps and bounds in the nineteenth century, but at the time of the Brontës there were still many treatments that we would find laughable or shocking. Arsenic, for example, was freely available and was even used as an aphrodisiac or as a treatment for men with erectile dysfunction (two words I never thought I’d find myself typing in my Brontë blog). Cough medicines given to children would often contain a range of potentially hazardous ingredients, including opiates which are closely related to today’s heroin. Laudanum itself was a tincture of opium, meaning that it contained around ten percent powdered opiate dissolved in alcohol. It was extremely addictive, but also available freely without prescription from apothecaries such as the one on Haworth’s Main Street.

Laudanum was used extensively to treat a wide range of conditions, but its most common medical usage was for pain relief, to suppress coughing and to treat restlessness and insomnia. It was also used, however, for its narcotic properties, making it the drug of choice for many people right across the British Isles, and it was these properties that Branwell sought.

One of the most famous laudanum users of the nineteenth century was the author and essayist Thomas de Quincey, and he gave a frank and often harrowing account of his relation with the drug in his 1821 masterpiece Confessions Of An English Opium-Eater. De Quincey consumed a huge amount of opium and laudanum on a daily basis (whilst many opium addicts used about ten drops a day he at one point was using eight thousand drops a day), and he described the effect it had upon his sleep and dreams:

‘For this and all other changes in my dreams were accompanied by deep-seated anxiety and gloomy melancholy, such as are wholly incommunicable by words. I seemed every night to descend, not metaphorically, but literally to descend, into chasms and sunless abysses, depths below depths, from which it seemed hopeless that I could ever reascend. Nor did I, by waking, feel that I had reascended. This I do not dwell upon; because the state of gloom which attended these gorgeous spectacles, amounting at last to utter darkness, as of some suicidal despondency, cannot be approached by words. The sense of space, and in the end, the sense of time, were both powerfully affected. Space swelled, and was amplified to an extent of unutterable infinity. Buildings, landscapes, &c., were exhibited in proportions so vast as the bodily eye is not fitted to receive. I sometimes seemed to have lived for 70 or 100 years in one night; nay; sometimes had feelings representative of a millennium passed in that time, or, however, of a duration far beyond the limits of any human experience.’

This powerful passage seemed to chime with one Brontë particularly – not Branwell, but Emily Brontë. The unending nightmarish dream is reminiscent of the one Lockwood experiences at Wuthering Heights, where he hears the interminable preaching of Jabes Branderham, where each sermon has 490 parts, each as long as a sermon itself. De Quincey talks about being trapped in the ‘depths below depths’ at night that he cannot reascend from, and that reminds one of Emily’s seminal poem The Night Is Darkening Round Me:

‘The night is darkening round me,

The wild winds coldly blow;

But a tyrant spell has bound me,

And I cannot, cannot go.

The giant trees are bending

Their bare boughs weighed with snow;

The storm is fast descending,

And yet I cannot go.

Clouds beyond clouds above me,

Wastes beyond wastes below;

But nothing drear can move me;

I will not, cannot go.’

De Quincey also outlined one reason that laudanum was the drug of choice for so many in the nineteenth century – it was cheap, and so it cost less to enter an oblivion through opium than it would through the purchase of alcohol.

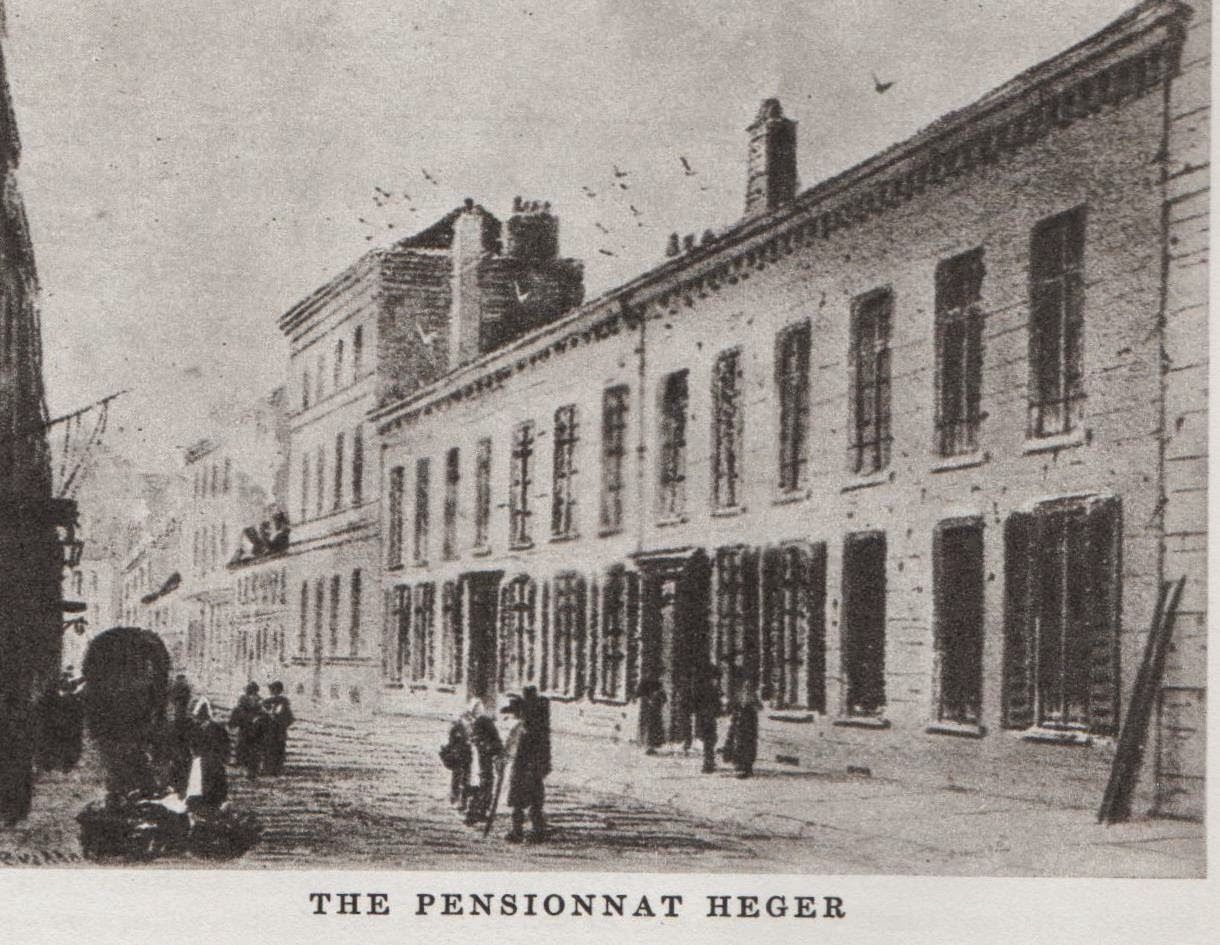

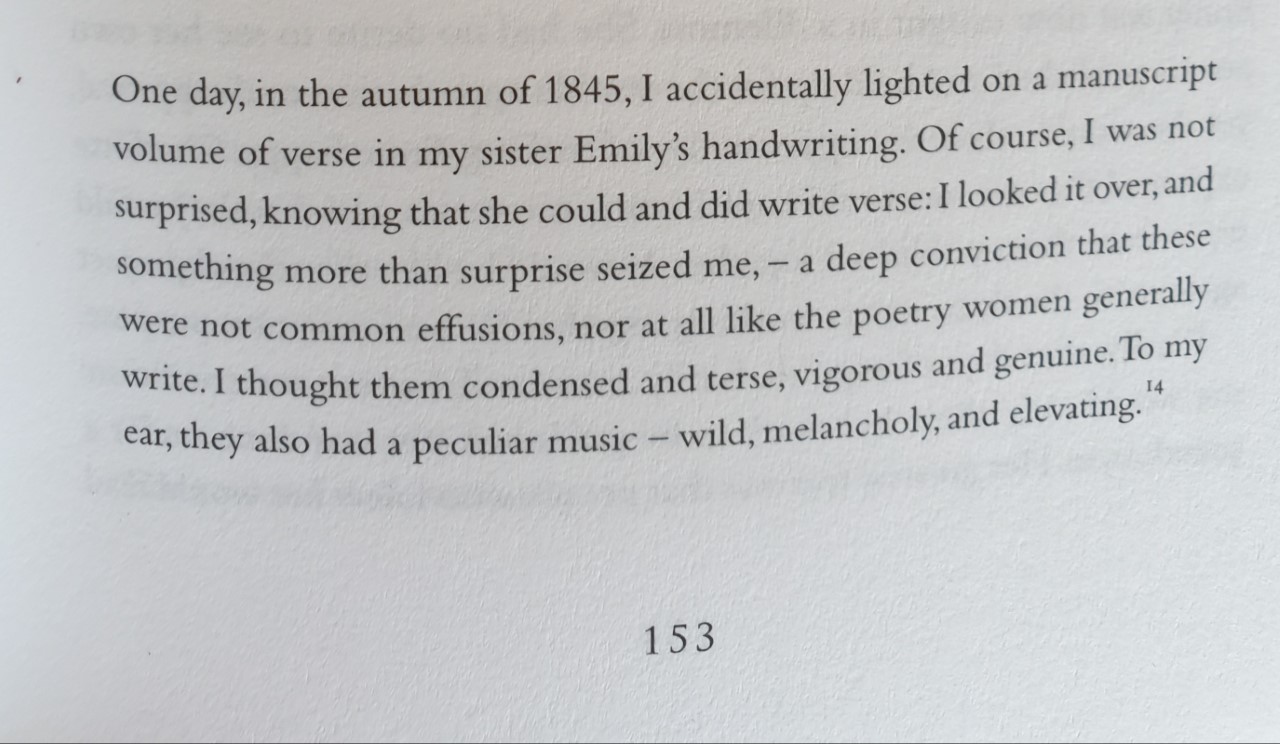

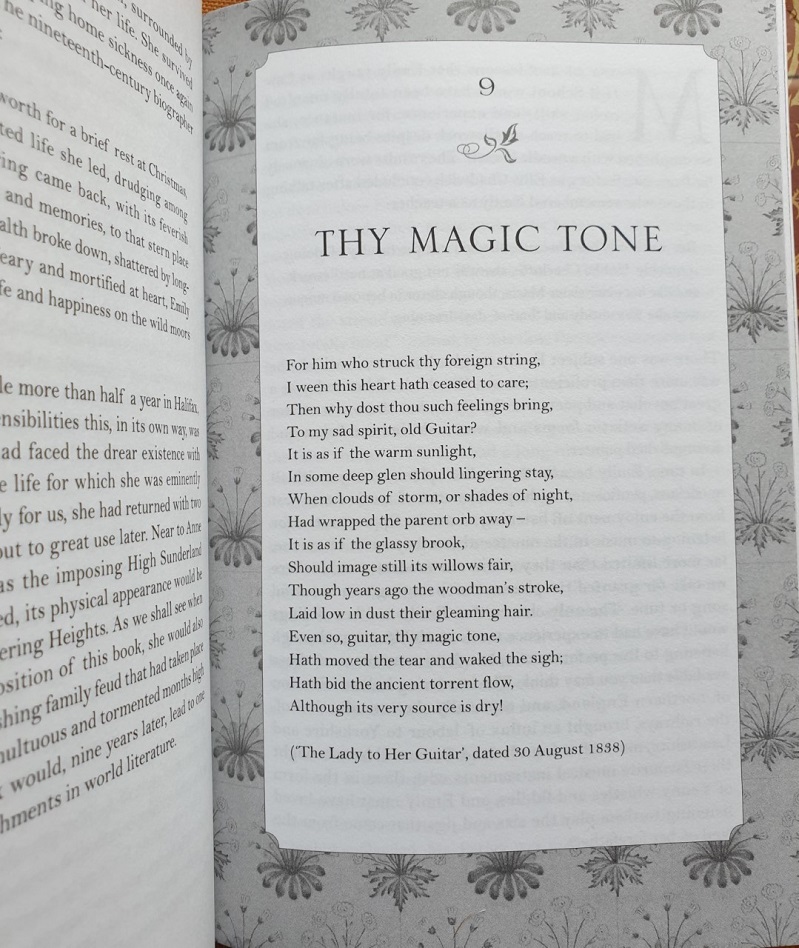

The Brontës were fans of De Quincey’s work, and sent him a copy of Poems By Currer, Ellis And Acton Bell, but it could be that Emily learnt personally about the effect of laudanum and opiates by watching the impact it had on her brother Branwell or through conversations with him. We also see evidence of the knowledge of how opium works, and the effect it produced, in Charlotte’s Roe Head Journal written whilst she was a teacher in the Mirfield school run by Margaret Wooler:

‘The toil of the day, succeeded by this moment of divine leisure, had acted on me like opium & was coiling about me a disturbed but fascinating spell, such as I never felt before. What I imagined grew morbidly vivid. I remember I quite seemed to see, with my bodily eyes, a lady standing in the hall of a gentleman’s house, as if waiting for some one.’

Branwell Brontë took solace in laudanum, alcohol and opium to forget his anxieties and troubles. He had a troubled life, and yet we must also remember that he was very talented too, and could be kind and loving. Nevertheless, he would often have entered the doors of the Lambert Apothecary at the top of Main Street and purchased bottles of laudanum, as must many other Haworth locals. Thankfully, you won’t find anything like that in the Cabinet Of Curiosities today, although you can find a vast range of treasures within its mirrored and evocative interior. The wonderful television presenter Gyles Brandreth was in the shop today, along with a film crew, so it seems that the story of the Brontës, Haworth and its old apothecary is still one that fascinates us all.

Unfortunately this was rather a whistle stop tour of Haworth for me, albeit still a lovely one, so I haven’t yet been to the Anne Brontë 200 exhibition inside the parsonage itself. I will be returning in a couple of weeks, at which point I will be visiting the exhibition itself and I’ll bring you all a full report after that. In the meantime, keep happy and healthy, and remember this important slogan: Hands – put a Brontë book in your hands; Face – place it in front of your face; Space – find a quiet space to enjoy reading your Brontë book. I will see you again next Sunday for another new Brontë blog post.