The best laid plans of mice and men, and you know the rest. I had intended today’s post to be about the Brontës and torchlight, filled with pictures of yesterday’s torchlight parade in Haworth (it’s on today at 5 as well if you can make it). Alas, bad weather and a bus strike put an end to those plans, but there is an important anniversary to mark today: in today’s new post we’re going to look at Patrick Brontë in Dewsbury.

On the 5th of December 1809, the 32 year old Patrick began his curacy at Dewsbury All Saints Church (now Dewsbury Minster); it’s an especially significant date in the Brontë story as this marked Patrick Bronte’s arrival in Yorkshire. From thereon he moved parishes to Hartshead-cum-Clifton, and then Thornton, and finally Haworth. Let’s not run ahead of ourselves, for Patrick’s time as an assistant curate at Dewsbury was a fascinating one and gives us a remarkable insight into Patrick as a man rather than merely as a father.

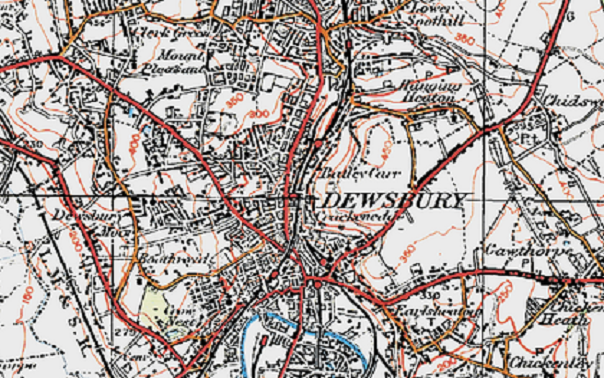

Dewsbury is today an unassuming town which is overshadowed by the nearby urban areas of Huddersfield, Wakefield and Leeds, but at the time Patrick arrived it was a town on the move. In the first half of the nineteenth century its population trebled to over 90,000 (compared to around 70,000 today), and the reason for this is that it had become an important hub on the wool processing trail – a town at the very heart of the industrial revolution.

Dewsbury’s minister was the Reverend John Buckworth. He had met Patrick before as they both belonged to the evangelical wing of the Church of England. Buckworth’s fame as a preacher was widespread, and he was also known as a hymn writer and the headmaster of a school for the poor – a ground breaking idea at the time. By 1809, however, he was increasingly in ill health, and in search of an energetic young priest to assist in his parochial duties. Patrick Brontë was his choice, and as 1809 neared its close he made the journey north from Shropshire to the West Riding of Yorkshire.

Patrick’s two years at Dewsbury were eventful ones, and he had to fight (quite literally) to win the respect of his new parishioners. The story is told of how one Sunday evening when Patrick was in sole charge of the church (Reverend Buckworth being away from the parish temporarily) he was astonished to hear the church bells ringing again after his services had ended.

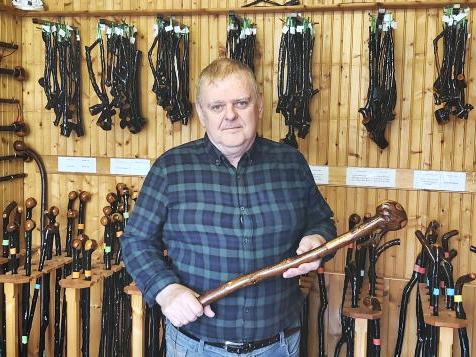

Unbeknownst to Patrick the parish bell ringing team had entered a competition and had popped into the bell tower for some extra practise. They must have been rather surprised when a furious Patrick burst in on them, accused them of ‘desecrating the Sabbath’ and drove them from the building. He was brandishing a shillelagh, a traditional Irish walking stick and club that few bell ringers would want to find themselves on the wrong end of.

His fiery temperament, and solid sense of what was right and wrong, was also shown at the 1810 Whitsun walk. Whitsuntide is also known as Pentecost and is traditionally the seventh Sunday after Easter. It was a long-standing tradition in Dewsbury for the churchgoers to march on Whit Tuesday (two days later) from the church to the village green of Earlsheaton where they would sing hymns.

On this particular march Patrick strode out with the choirboys beyond him, but their path was soon blocked by a large man making oaths. Without thinking twice, Patrick picked up the man by his collar and threw him into some nearby bushes. Some were worried that the man, notorious for his violence in the area, would be waiting for them on the return journey. He was, but when Patrick fronted him up once more he stepped aside. One of the choirboys later recalled the incident:

‘The bully came from Gawthorpe, near Osset, and was a notorious cockfighter and boxer, and much addicted to drinking… what happened was talked about for many a Sunday.’

It must have been talked about within the family for many years after as well, for it found its way into Charlotte Brontë’s novel Shirley as two Whitsuntide marches clash:

‘Old Helstone moved on. Quickening his step, he marched some yards in advance of his company. He had nearly reached the other sable leaders, when he who appeared to act as the hostile commander-in-chief – a large, greasy man, with black hair combed flat on his forehead – called a halt. The procession paused. He drew forth a hymn book, gave out a verse, set a tune, and they all struck up the most dolorous of canticles.

Helstone signed to his bands. They clashed out with all the power of brass. He desired them to play “Rule, Britannia!” and ordered the children to join in vocally, which they did with enthusiastic spirit. The enemy was sung and stormed down, his psalm quelled. As far as noise went, he was conquered.

“Now, follow me!” exclaimed Helstone; “not at a run, but at a firm, smart pace. Be steady, every child and woman of you. Keep together. Hold on by each other’s skirts, if necessary.”

And he strode on with such a determined and deliberate gait, and was, besides, so well seconded by his scholars and teachers, who did exactly as he told them, neither running nor faltering, but marching with cool, solid impetus – the curates, too, being compelled to do the same, as they were between two fires, Helstone and Miss Keeldar, both of whom watched any deviation with lynx-eyed vigilance, and were ready, the one with his cane, the other with her parasol, to rebuke the slightest breach of orders, the least independent or irregular demonstration – that the body of Dissenters were first amazed, then alarmed, then borne down and pressed back, and at last forced to turn tail and leave the outlet from Royd Lane free. Boultby suffered in the onslaught, but Helstone and Malone, between them, held him up, and brought him through the business, whole in limb, though sorely tried in wind.

The fat Dissenter who had given out the hymn was left sitting in the ditch. He was a spirit merchant by trade, a leader of the Nonconformists, and, it was said, drank more water in that one afternoon than he had swallowed for a twelvemonth before. Mr. Hall had taken care of Caroline, and Caroline of him. He and Miss Ainley made their own quiet comments to each other afterwards on the incident. Miss Keeldar and Mr. Helstone shook hands heartily when they had fairly got the whole party through the lane. The curates began to exult, but Mr. Helstone presently put the curb on their innocent spirits. He remarked that they never had sense to know what to say, and had better hold their tongues; and he reminded them that the business was none of their managing.’

Patrick’s reputation in Dewsbury was further enhanced when he saved the life of a local boy. Patrick loved taking long walks, something his children would also later delight in, and one of his favourite stretches was by the side of the River Calder. On one of these perambulations he saw a group of local boys playing on the bank but then disaster struck and one of them fell (or was pushed in). Patrick sprang into action and leapt into the river, plucked the boy out of the water and swam him back to the shore before taking him home to his family. Drowning was a very common form of death in the early nineteenth century, but thankfully that was one child saved from becoming a statistic.

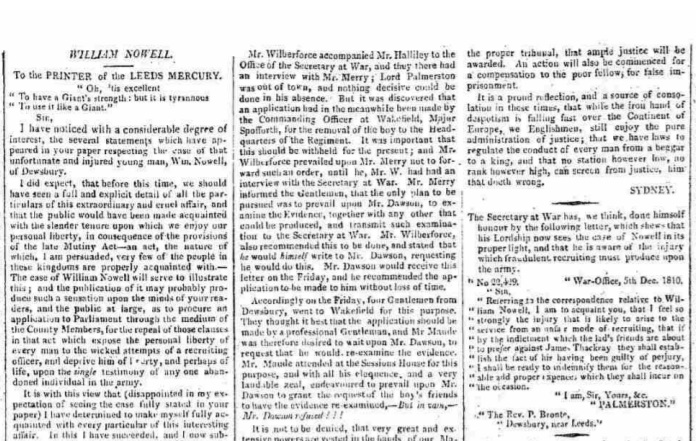

Patrick Brontë’s time in Dewsbury was not only tumultuous for the town, but for the country as a whole. Britain was engaged in the Napoleonic Wars and young men were being recruited into the army in large numbers, being given ‘the King’s shilling’ in return. This led to a notorious court case in which Patrick played a major part.

On 25th November 1810 a Dewsbury man named William Nowell was arrested for desertion. A soldier called James Thackray had testified that he had recruited Nowell into his regiment at the Lee Horse Fair but that he had not reported for duty. Nowell insisted that he had not been at the horse fair and produced witnesses to swear this, but the judge refused to accept this evidence and Nowell was confined to prison.

Dewsbury was in uproar at this miscarriage of justice, and Patrick Brontë was one of four local men who spoke to magistrates on Nowell’s behalf, to no avail. Patrick then wrote to the Secretary of War, Lord Palmerston, to plead the case and a delegation including William Wilberforce travelled to the ministry to add their support. Palmerston (and Wilberforce) had been at Cambridge with Patrick, but we can’t know whether that influenced his decision or not. A full hearing was arranged at which Patrick, and 25 other witnesses, spoke on Nowell’s behalf. Nowell was released from prison, but a year later Thackray was found guilty of perjury and transported to Australia for seven years.

On 15th December 1810 a jubilant Patrick gave a full account of the case to the Leeds Mercury, opening it with a quote from Shakespeare’s Measure For Measure: “’Tis excellent to have a giant’s strength: but it is tyrannous to use it like a giant.”

In his time at Dewsbury Patrick had saved a child’s life, dispatched a bully into a ditch, righted a miscarriage of justice, and stood up, with a shillelagh, for the church doctrines which meant so much to him. It’s a real insight into his character: Patrick Brontë was certainly not a man to be messed with. Within three years of his arrival in the county he had met and married another incomer to Yorkshire: Maria Branwell. The rest is history. I hope to see you again next Sunday for another new Brontë blog post.