Last week we looked at the infamous letter that Robert Southey, the then poet laureate, sent to a 19 year old Charlotte Brontë on 12th March 1837. Alas we don’t have the initial letter which Charlotte sent to her poetic hero, but that doesn’t mean that was the end of the correspondence. Rather lesser known is what happened after that initial exchange, and it shines a light on Charlotte and Southey, and on Branwell Brontë and William Wordsworth. We’re going to examine this in today’s Brontë blog post.

You may remember that Charlotte had written to Southey at the start of the year 1837; although we don’t have her letter she had clearly sent him some of her verse, and asked his opinion of it – expressing all the while her desire to follow in his footsteps and become a poet. Alas, Robert Southey’s response was very much of his time: he wrote back to say that poetry was not and could not be a woman’s work, for when she was married and had children she would have no time for it nor would she lack for excitement.

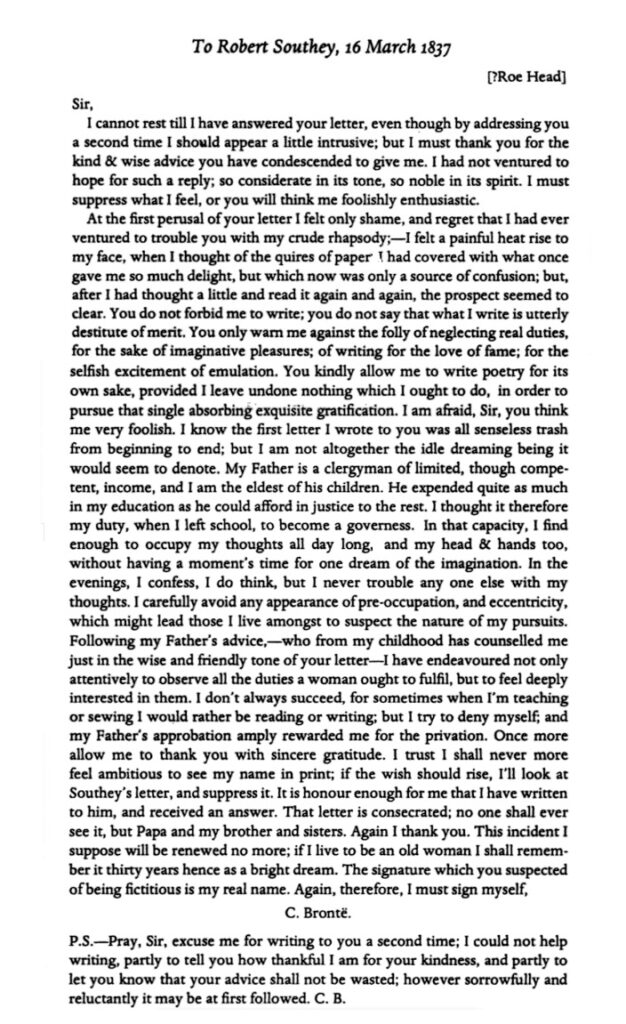

We know from her novels and letters that Charlotte was a very forthright woman, unafraid of expressing her opinions and of standing up for her rights, so what happened next may seem surprising. She wrote straight back to Southey to let him know how delighted she was with his response! Charlotte’s letter of 16th March seems full of both joy and sadness, but it’s a fascinating glimpse of her life and thoughts at this time:

Charlotte has now ‘realised’ that her work is a ‘crude rhapsody’ and ‘senseless trash’, but she is only grateful that Southey has kindly allowed her to continue writing verse for its own sake. If only ‘Word’ allowed me to insert an angry faced emoji here! Charlotte kept both Southey’s first letter and the envelope it came in, upon which she has written: ‘Southey’s advice, to be kept forever’. Above it, however, is a faint pencilled annotation which was perhaps added at a later date, when Charlotte was beginning to have second thoughts about the impact of his advice. It simply reads ‘melpomene’ – the name of the Greek Muse of tragedies!

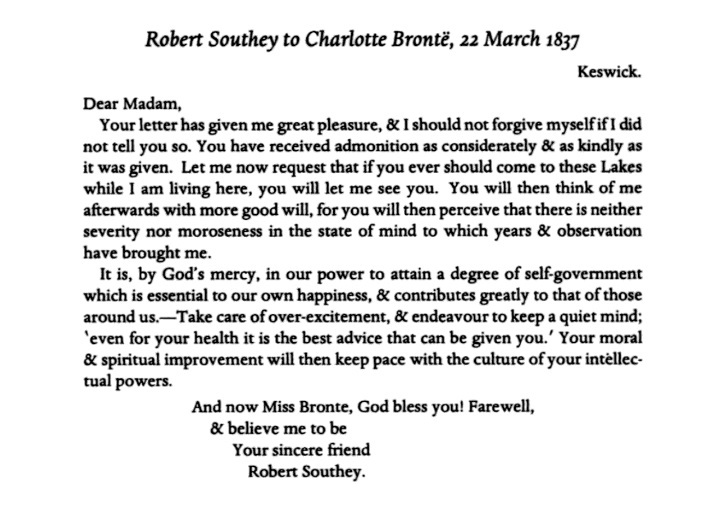

I say Southey’s ‘first letter’ in the paragraph above, because the communications didn’t stop there. In fact, on 22nd March 1837 he wrote again to Charlotte Brontë, as we can see below:

It seems the poet laureate was so delighted with Charlotte’s response that he actually invited her to visit him at his grand home Greta Hall in the Lake District (that’s it at the head of this post)! He declares afterwards that she will think of him with more goodwill, for he only offered kindly advice and is neither severe nor morose. Whether people today would think of him with anything approaching goodwill is probably another matter.

Charlotte never got the chance to visit Southey. She made her first journey to the Lakes in 1850, by which time Robert Southey had been dead for seven years, but it seems likely to me that he would have been on her mind as she passed through the streets and hills he had known so well.

There is further, fascinating, evidence of the impact Charlotte’s letters made on Southey. On 27th March 1837 he wrote to Caroline Bowles, the artist and poet. Strangely enough, considering the advice he had given to Charlotte, Southey had actually encouraged Caroline to write poetry and suggested that they write together. In 1839, Caroline became Robert Southey’s second wife.

The letter from Robert to Caroline mentioned above has a section of great interest to us, so I reproduce it below:

‘I sent a dose of cooling admonition to the poor girl whose flighty letter reached me at Buckland. It was well taken, and she thanked me for it. It seems she is the eldest daughter of a clergyman, has been expensively educated, and is laudably employed as a governess in some private family. About the same time that she wrote to me, her brother wrote to Wordsworth, who was disgusted with the letter, for it contained gross flattery to him, and plenty of abuse of other poets, including me. I think well of the sister from her second letter, and probably she will think kindly of me as long as she lives.’

From this we can deduce that Southey had also discussed Charlotte with William Wordsworth himself who, recognising the name, produced a letter that he had recently received from her brother Branwell Brontë. As Branwell wrote to Wordsworth at around the same time as Charlotte wrote to Southey, perhaps Charlotte and Branwell, at that time very close, had resolved together to write to their favourite poets for feedback on their youthful work?

Of course, undoubtedly Charlotte has had the last laugh, for she is now far more famous and celebrated than Robert Southey. Like her sisters, she was a writer of vast talent, of genius, and yet in her case it was a genius always beset with self-doubt, and perhaps this is why she so readily accepted Southey’s advice to give up her dream of becoming a writer.

By a coincidence this very weekend marks the anniversary of a further letter which shows that even in adulthood, at the height of her fame, Charlotte could not think highly of her own poetry. She had received a letter from a Miss Alexander of Lupset Hall near Wakefield. Somehow, Miss Alexander had deduced that Currer Bell, celebrated author of Jane Eyre, was actually the unassuming Charlotte Brontë of Haworth. On 18th March 1850, Charlotte wrote back to Miss Alexander saying that she had hoped to keep her identity a secret, but she also gives her opinion of Poems by Currer, Ellis and Acton Bell, the first Brontë book to be published and one which Miss Alexander had clearly asked for an opinion on. Charlotte writes:

‘As to the little book of rhymes it has no other title than Poems by Currer, Ellis and Acton Bell published by Smith, Elder & Co. 65 Cornhill. Let me warn you that it is scarcely worth your while to send for it. It is a collection of short fugitive pieces; my own share are chiefly juvenile productions written several years ago, before taste was chastened or judgment matured – accordingly they now appear to me very crude.’

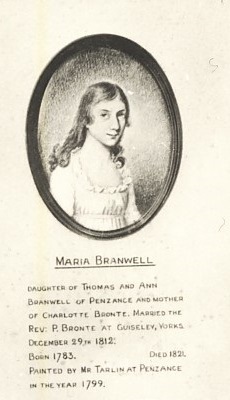

There are great similarities in the self-critique of 1850 and of 1837. Thirteen years had passed since Charlotte’s reply to Robert Southey, but it seems that his pronouncement on her work was still very much on her mind. Thankfully it didn’t stop her writing, but it is time for me to stop writing today’s post, but not before we pay a quick Mother’s Day tribute to Maria Branwell, mother of the Brontës, and to all of you who are mothers or grandmothers. Have a great day, and I hope to see you next week for another new Brontë blog post.