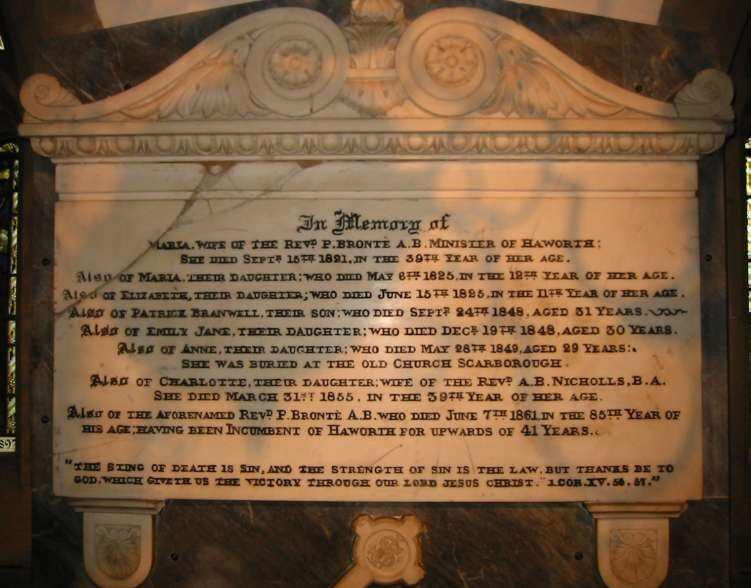

The sixth of May and fifteenth of June are difficult days for lovers of the Brontë family, as it was on these dates 193 years ago that the eldest siblings Maria Brontë and Elizabeth Brontë died of consumption, what we now know as tuberculosis. Their loss was dreadful to their family, and can still be felt by us today. Certainly they remained ever on third sister Charlotte’s mind, as we can see from her letter of 13th June 1849, sent from Filey to W.S. Williams:

‘A year ago had a prophet warned me how I would stand in June 1849, how stripped and bereaved, had he foretold the autumn, the winter, the spring of sickness and suffering to be gone through I should have thought this can never be endured. It is over. Branwell, Emily, Anne are gone like dreams – gone as Maria and Elizabeth went twenty years ago. One by one I have watched them fall asleep on my arm and closed their glazed eyes – I have seen them buried one by one.’

Maria and Elizabeth Brontë were sent to the Clergy Daughter’s School in Cowan Bridge in Westmorland in July 1824, with Charlotte joining them there two months later. They already had some taste of school, having earlier attended the exclusive Crofton Hall School at Wakefield for a term. Cowan Bridge, however, was a very different school run on very different lines by the calvinist minister Carus Wilson.

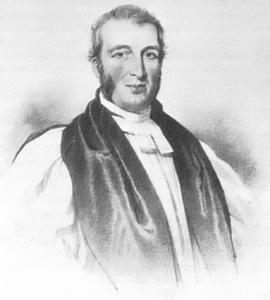

Wilson sued Elizabeth Gaskell after the publication of her biography of Charlotte Brontë, and had many references to him removed. It has been said that the deaths that claimed Maria and Elizabeth were due to the errors of a cook, but Wilson himself cannot be fully exonerated.

He was, by any standards, a hell-fire preacher of extreme views and extreme ferocity. An arch Calvinist, he believed that one sin would condemn a person to eternal torture in Hell, with no opportunity to escape this fate but for a group of people called the ‘Elect’, which he was of course one of.

He attacked society, his congregation and less severe clergy alike. One sermon of his began:

‘The worldliness even of the most moral and (in the general acceptance of the term) respectable Clergyman, oh! How it eats as a canker at the roots of his pastoral usefulness, and discourages many a young disciple who was beginning to turn his face Zionwards.’

Who was the target of this sermon of Wilson’s? It was delivered to mark a visit from the Bishop of Chester.

Of the 53 pupils at the school at the time of the Brontës, seven died, and others were sent home severely ill who may also have died. This wasn’t the end of deaths during Wilson’s career as a headmaster, indeed they occurred continually throughout his decades in this role. By 1840, 15 years after the deaths of Maria and Elizabeth Brontë, Wilson had moved his school to Casterton in Westmorland. The Leeds Intelligencer of 25th January 1840 reports that 70 pupils at the school were now suffering from typhoid, and that three had recently died.

In 1857, Wilson appointed a new head at Casterton, Dorothea Beale. She was a very different person to Wilson, and later became known as a suffragist and social reformer. Beale was horrified at what she found at the school, and resigned a year later. She complained about ‘the low moral tone of the school’, and ‘the want of sympathy and love’, as ‘nothing can flourish if love be not the ruling incentive.’

It seems that Carus Wilson had learned little in the 40 years after the Brontës’ deaths. Perhaps the defining verdict on the school should be left to Charlotte, who famously described it as Lowood in ‘Jane Eyre’: ‘That forest-dell, where Lowood lay, was the cradle of fog and fog-bred pestilence; which, quickening with the quickening spring, crept into the Orphan Asylum, breathed typhus through its crowded schoolroom and dormitory, and, ere May arrived, transformed the seminary into a hospital’

Charlotte was adamant in later years that Cowan Bridge had in fact been much worse than the Lowood of her novel, insisting that: ‘Had I told all the truth, I might indeed have made it far more exquisitely painful.’

As it is we have to read the painful depiction of Maria Brontë as Helen Burns, the kind, bright, uncomplaining young woman who is singled out for especially harsh treatment for being disorganised, and who eventually dies with Jane by her side.

In reality, Charlotte could not be by Maria’s side as she breathed her last breath on May the sixth 1825, as she, Elizabeth and Emily were still at the school. It was Patrick who had to close her glazed eyes, just as a month later he had to do for his second daughter Elizabeth who was sent home to Haworth on 31st May 1825 in ‘ill health’, along with a bill for her stay at the school.

It was a tragic event that should never have been allowed to happen, and the Brontës suffered two huge losses. We Brontë lovers suffer too, for who knows what they could have achieved if they had lived longer? They would surely have provided support and companionship to Anne, then just five years old, as she grew up.

Let us think no longer of the cruelties of Cowan Bridge, but instead picture two kind, bright and happy children full of promise who would always be remembered by their father and siblings, always loved. Even so, it is impossible on this day not to also think of Charlotte’s mournful yet beautiful verdict on Emily, and apply it to Maria Brontë and Elizabeth Brontë too:

‘She has died in a time of promise – we saw her torn from life in its prime.’

The world will always, rightly, remember Charlotte, Emily, Anne and Branwell Brontë – let us also take a moment of silence to remember Maria and Elizabeth.

So so sad,I wonder if they would also have been great novelists? Poor little girls.

Harsh, terrible days. Wouldn’t be allowed to happen now, Mr. Carus Wilson was a cruel man, u can see it in his eyes on his portrait.