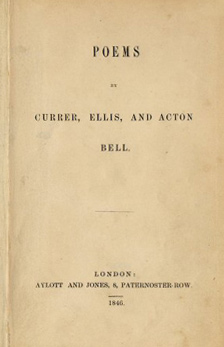

We’ve looked previously at the possible reasons for the choice of Currer, Ellis and Acton Bell as the pen names of the Brontë sisters Charlotte, Emily and Anne, and the possible reasons for them deciding to use pseudonyms at all. In today’s post we’re going to look at two letters written on this week in 1850 and 1852 which gave an insight into the separation that Charlotte Brontë made between herself and her alter ego Currer Bell.

We’ve also previously looked at the story from the Brontë childhood when Patrick made his children wear a mask and answer a question, thus allowing him to get an insight into their character free of their usual reserve. It seems to me that after the passing of her sisters Emily and Anne, Charlotte clung on to Currer Bell as another mask.

Since the summer of 1849 the true identity of Currer Bell had been known to a select few. It was then that Currer and Acton visited the publisher George Smith and revealed that they were really Charlotte and Anne Brontë, daughters of a curate from a moorside Yorkshire parish. Charlotte also accidentally revealed Emily’s identity to Smith, despite having been sworn to keep it a secret. We know that by this time their father Patrick knew of their writing identity, but that brother Branwell died without ever knowing his sisters had had a word published. We see this in Charlotte Brontë’s letter to W. S. Williams of 2nd October 1848:

‘My unhappy brother never knew what his sisters had done in literature – he was not aware that they had ever published a line… Now he will never know.’

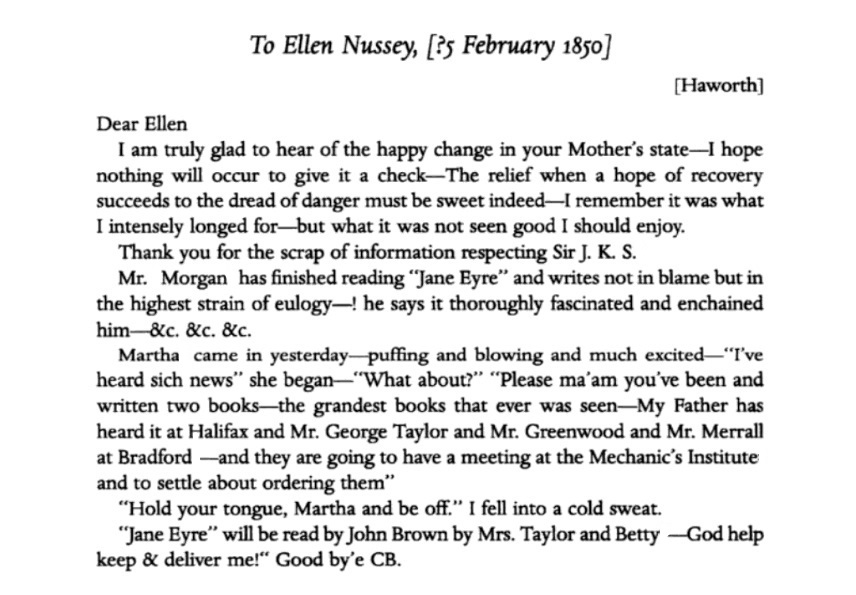

He was not the only one for whom the secret of Currer Bell remained, long after the publication of Jane Eyre had made such a huge and immediate impact on the world of literature. This mask of secrecy remained even for one of those closest to Charlotte: Martha Brown, the long time servant at Haworth Parsonage who had become increasingly close to Charlotte after the passing of Emily and Anne. By the start of 1850 however the mask was slipping, as we see in Charlotte’s letter to Ellen Nussey of the 5th of February:

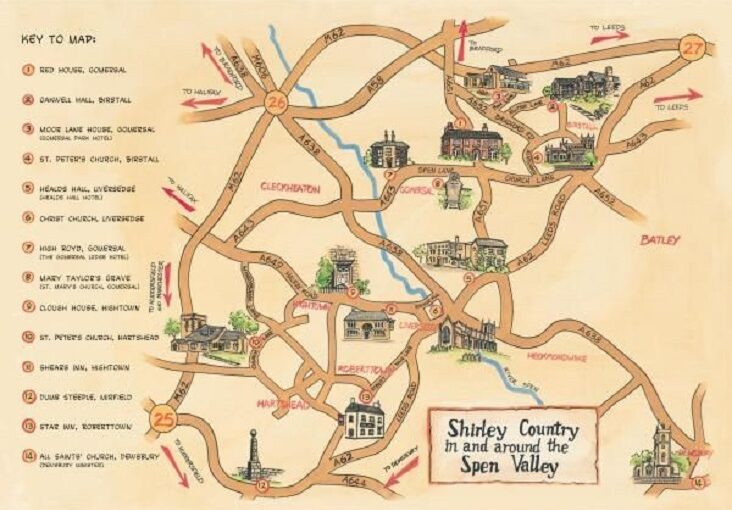

Charlotte breaks into a cold sweat at the revelation that the true identity of Currer Bell has been guessed at in her corner of Yorkshire, and that some of those she knows well will soon know her as the author of Jane Eyre. It is not this novel which has led to the discovery, however, but its successor Shirley. Charlotte had set the book in the Spen Valley district around Mirfield and Dewsbury that she knew well, and many of its characters were thinly disguised portraits of local people, from her own sisters to the Taylors of Gomersal and local curates including Arthur Bell Nicholls. It seems that some of the book lovers of the area had looked at the clues within the book, considered its predecessor as well, and concluded that the bookish daughter of the curate of Haworth had to be the author.

One of the biggest sources of clues came in the opening chapter of Shirley, where a series of curates engage in ecclesiastical arguments. These curates were all based on those known by Charlotte, including Reverend Joseph Grant who was portrayed as Reverend Donne (‘donne’ being French for give, or grant). It’s a rather brutal portrait of a man who had served as Patrick Brontë’s assistant curate in 1844 and 1845, and by 3rd April 1850 (in a letter to W. S. Williams) we see that he and the other curates know of their role in Currer Bell’s novel:

‘While I have heard little condemnation of Shirley – more than once have I been deeply moved by manifestations of even enthusiastic approbation. I deem it unwise to dwell much on these matters, but for once I must permit myself to remark that the generous pride many of the Yorkshire people have taken in the matter has been such as to awaken and claim my gratitude – especially since it has afforded a source of reviving pleasure to my Father in his old age. The very Curates – poor fellows! shew no resentment; each characteristically finds solace for his own wounds in crowing over his brethren. Mr. Donne was – at first, a little disturbed; for a week or two he fidgeted about the neighbourhood in some disquietude – but he is now soothed down, only yesterday I had the pleasure of making him a comfortable cup of tea and seeing him sip it with revived complacency. It is a curious fact that since he read Shirley he has come to the house oftener than ever and been remarkably assiduous and eager to please. Some people’s natures are veritable enigmas. I quite expected to have one good scene at the least with him, but as yet nothing of the sort has occurred – and if the other curates do not tease him into irritation, he will remain quiet now.’

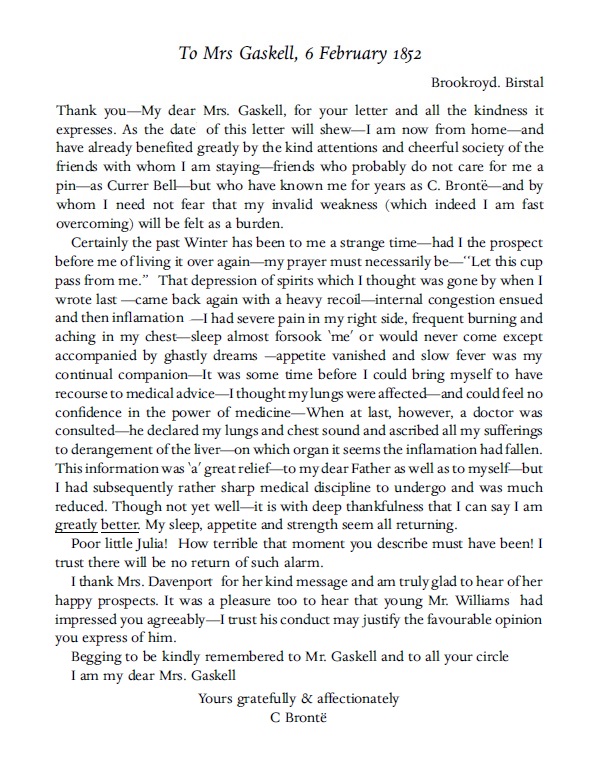

We see then that by April 1850 the identity of Charlotte Brontë as Currer Bell was fully known in her locale and amongst her acquaintances, so how did Charlotte deal with that? We get an insight into this in a mournful letter which Charlotte wrote to Elizabeth Gaskell on 6th February 1852, 170 years ago today:

In this letter Charlotte details the horrors of a winter in which she has suffered from a severe bout of depression which frequently haunted her, and from a physical illness which she and her father had suspected was tuberculosis. It is a winter she never wants to experience again, but there has been one solace; Charlotte writes the letter from Brookroyd, the home of Ellen Nussey. She has turned for comfort to the people who ‘do not care for me a pin as Currer Bell but who have known me for years as C. Brontë.’

In Charlotte’s mind there was always the distinction between Currer Bell the writer and Charlotte Brontë the person – and it was the latter which would always take precedence. She was not merely the author of Jane Eyre she was the curate’s daughter from Haworth, and it was that side of her personality which she prized most highly, and the people who loved her as Charlotte Brontë were the people who she loved most in return.

Like all authors, Charlotte Brontë was not her work – she was an ordinary person who created extraordinary things, and in the works of Charlotte and her sisters rarely the creative magic led to works of true genius. I hope to see you again next week for another new Brontë blog post.

Thank you some excellent information and very thankful for it