I woke to the sound of my smoke detectors beeping angrily at six this morning. It’s never the perfect alarm call, and it sent me scurrying around the house in search of smoke or fire. None could be found thankfully, but as it then started beeping again there was no chance of further sleep. On the plus side, it’s provided me an ideal opportunity to write this week’s blog on the subject of fire and the Brontës.

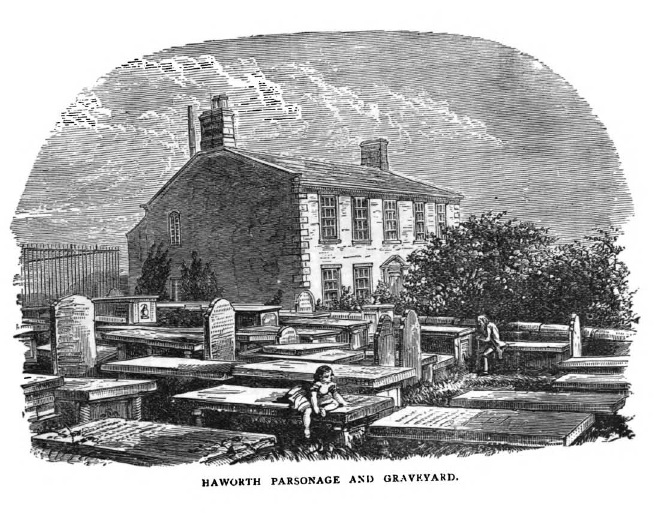

There were no smoke detectors or fire alarms in the early nineteenth century of course, but if there were then you can be sure that Patrick Brontë would have filled the parsonage with them. Ellen Nussey, in her ‘Reminiscences’, recalled Patrick’s acute awareness of the dangers fire posed, and the actions he took to alleviate the risks:

‘Mr. Brontë’s horror of fire forbade curtains to the windows; they never had these accessories to comfort and appearance till long after Charlotte was the only inmate of the family sitting room, – she then ventured on her innovation when her friend was with her; it did not please her father but it was not forbidden.’

Ellen elucidated further on his fear, and the effect it had on his daughters:

‘The only dread he had was of fire [Ellen’s italics], and this dread was so intense it caused him to prohibit all but silk or woollen dresses for his daughters; indeed, for any one to wear any other kind of fabric was almost to forfeit his respect.’

Patrick’s fear was not an unfounded phobia, however, but based on the very real threats that were around him and his family. These were the days of open fireplaces and candle light, as well as the days of increasingly voluminous women’s clothing often made from highly flammable fabrics. As a parish priest Patrick would have had to bury many people, often girls, whose dress had fluttered across a flame and caught light. With many layers of clothing also worn, the effects of an encounter with fire in this way would often prove fatal.

Patrick’s response, as we have seen, was to ban curtains that could be ignited by a candle’s flame, and to insist that his daughters wore wool or silk as these were less immediately flammable. If we take a look through nineteenth century archives, or watch the excellent documentary ‘Hidden Killers Of The Victorian Home’, we soon see that many families were not so fortunate as the Brontës, and deaths by fire happened across the country on a daily basis.

I say ‘not so fortunate’ as, despite Patrick’s precautions, there was eventually a fire in Haworth Parsonage but thanks to the quick actions of Anne and Emily the consequences were less serious than they could so easily have been.

John Greenwood, the Haworth stationer who was a close family friend, recalled the story of how Anne, as was her wont, stopped to look in upon her brother on her way to bed one night, and found that Branwell had fallen asleep while trying to read by candlelight and his room was on fire. With the help of Emily, the tallest and strongest in the house, she dragged Branwell from the room and they doused the flames with pitchers of water. Without their quick thinking and quick actions it could have been so much worse.

This scene remained, quite understandably, on their minds, and Charlotte must have been well aware of it as well, because she used it for a powerful moment in ‘Jane Eyre’:

‘Something creaked: it was a door ajar; and that door was Mr. Rochester’s, and the smoke rushed in a cloud from thence. I thought no more of Mrs. Fairfax; I thought no more of Grace Poole, or the laugh: in an instant, I was within the chamber. Tongues of flame darted round the bed: the curtains were on fire. In the midst of blaze and vapour, Mr. Rochester lay stretched motionless, in deep sleep. “Wake! wake!” I cried. I shook him, but he only murmured and turned: the smoke had stupefied him. Not a moment could be lost: the very sheets were kindling, I rushed to his basin and ewer; fortunately, one was wide and the other deep, and both were filled with water. I heaved them up, deluged the bed and its occupant, flew back to my own room, brought my own water-jug, baptised the couch afresh, and, by God’s aid, succeeded in extinguishing the flames which were devouring it.’

Branwell has inspired Rochester and Bertha in this scene, he is the inadvertent fire starter and its potential victim, but thankfully Anne had been on hand to be the rescuing Jane. Later in Charlotte’s novel we find that Bertha has succeeded and burnt down Thornfield Hall, destroying herself, but not quite Rochester, in the process.

In Anne’s novels we see fire represent something very different – it is not danger, but passion, love. In the first section ‘The Tenant Of Wildfell Hall’, Gilbert calls upon Helen:

‘”How dismal you are, Helen! Why have you no fire?” I said, looking round on the gloomy apartment.

“It is summer yet,” she replied.

“But we always have a fire in the evenings, if we can bear it; and you especially require one in this cold house and dreary room.”

“You should have come a little sooner, and I would have had one lighted for you: but it is not worth while now.”’

Helen has no fire, metaphorically, because she has no love and at that point, no hope; her hearth and heart are cold, but as we see later, like the winter rose with snow upon its leaves it can still be rekindled.

In ‘Agnes Grey‘, Agnes is cheered by a chance encounter with Reverend Weston that to some may seem insignificant, but to Agnes it has warmed her world:

‘Well! what is there remarkable in all this? Why have I recorded it? Because, reader, it was important enough to give me a cheerful evening, a night of pleasing dreams, and a morning of felicitous hopes. Shallow-brained cheerfulness, foolish dreams, unfounded hopes, you would say; and I will not venture to deny it: suspicions to that effect arose too frequently in my own mind. But our wishes are like tinder: the flint and steel of circumstances are continually striking out sparks, which vanish immediately, unless they chance to fall upon the tinder of our wishes; then, they instantly ignite, and the flame of hope is kindled in a moment.’

Whatever our dreams, let us all keep the flame of hope alive, and let us all bask in the warm glow that comes from a Brontë book. Oh, and let’s all make sure that our smoke detectors are in good working order and not likely to wake us at an altogether unholy hour on a Sunday morning.

It is amazing how we sometimes forget the relevance of daily life events being reflected in the books we read.