On this weekend 174 years ago two small, shy women were making their first visit to London – and it was to change literary history forever. They were Charlotte and Anne Brontë (home loving Emily had remained in Haworth) and their visit to London lasted four days between 7th and 11th of July. In today’s new post we’re going to look at a first hand account of their visit to England’s capital city (by the way the image at the top of this post is an 1848 painting of London by Carl Haag), from one who was by their side throughout much of it.

In a previous post we’ve looked at a detailed account that Charlotte Brontë gave of the visit to her great friend Mary Taylor. One of the many remarkable things in that letter was Charlotte’s account of a snowstorm that greeted them as they set out from Haworth to Keighley on July 7th – the weather is rather different at the moment!

The reason for the hasty journey from Haworth to London is well known. Up until that point the Brontë sisters had been writing under the pseudonyms of Currer, Ellis and Acton Bell but the typical machinations of Anne and Emily’s publisher Thomas Cautley Newby had led to suggestions that the Bells were in fact one person. To the Brontës integrity was everything (so who knows what they’d think of public life today?) so they determined to reveal their name in the only way they knew how – by finally revealing their true identities.

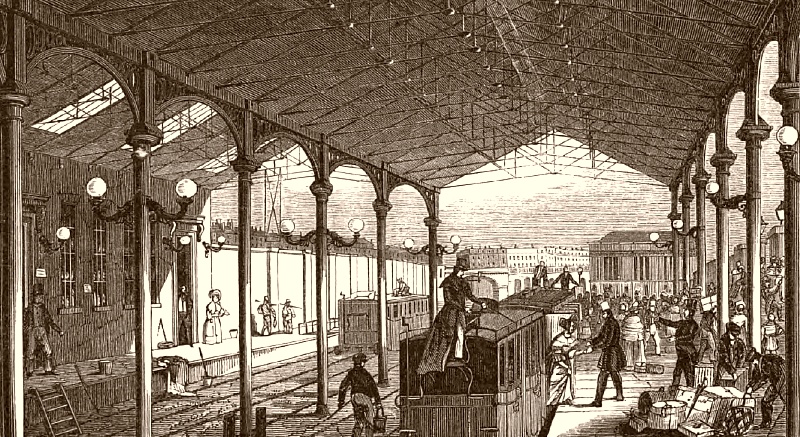

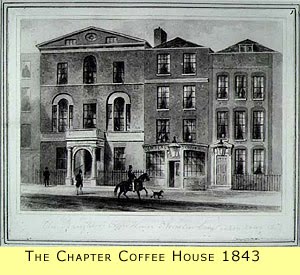

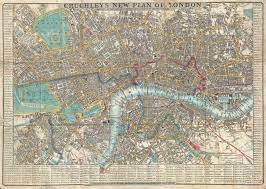

After arriving at Euston Station they made their way to lodgings at the Chapter Coffee House on Paternoster Row (the same location Charlotte had stayed in en route to Brussels six years earlier – it was the only place in London she knew), and from thence to Smith, Elder & Co at Cornhill. It was there they met Charlotte’s publisher George Smith, a young, wealthy, book loving man who had recently inherited the business from his father. It is Smith’s account, from the 1902 book A Memoir: With Some Pages Of Biography that we look at now:

“When we were about to publish Shirley – the work which, in the summer of 1848, succeeded Jane Eyre – we endeavoured to make an arrangement with an American publisher to sell him advance sheets of the book, in order to give him an advantage in regard to time over other American publishers. There was, of course, no copyright with America in those days. We were met daring the negotiations with’ our American correspondents by the statement that Mr. Newby had informed them that he was about to publish the next book by the author of Jane Eyre under her nom de plume of Acton Bell – Currer, Ellis, and Acton Bell being in fact, according to him, one person. We wrote to ‘Currer Bell’ to say that we should be glad to be in a position to contradict the statement, adding at the same time we were quite sure Mr. Newby’s assertion was untrue.

Charlotte Brontë has related how the letter affected her. She was persuaded that her honour was impugned. ‘With rapid decision’, says Mrs. Gaskell in her Life of Charlotte Brontë,‘Charlotte and her sister Anne resolved that they should start for London that very day in order to prove their separate identity to Messrs. Smith, Elder, & Co.’ With what haste and energy the sisters plunged into what was, for them, a serious expedition, how they reached London at eight o’clock on a Saturday morning, took lodgings in the ‘Chapter’ coffee-house in Paternoster Row, and, after an agitated breakfast, set out on a pilgrimage to my office in Cornhill, is told at length in Mrs. Gaskell’s Life of Charlotte Brontë.

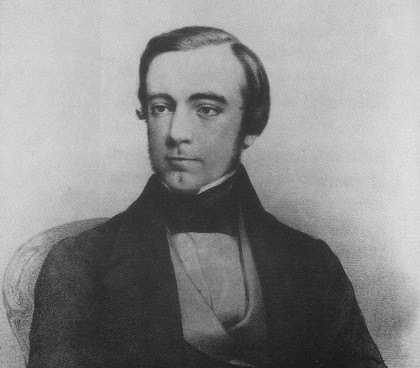

That particular Saturday morning I was at work in my room, when a clerk reported that two ladies wished to see me. I was very busy and sent out to ask their names. The clerk returned to say that the ladies declined to give their names, but wished to see me on a private matter. After a moment’s hesitation I told him to show them in. I was in the midst of my correspondence, and my thoughts were far away from ‘Currer Bell’ and Jane Eyre. Two rather quaintly dressed little ladies, pale-faced and anxious-looking, walked into my room ; one of them came forward and presented me with a letter addressed, in my own handwriting, to ‘Currer Bell, Esq.’ T noticed that the letter had been opened, and said, with some sharpness, ‘Where did yon get this from?’ ‘From the post-office’, was the reply; ‘it was addressed to me. We have both come that you might have ocular proof that there are at least two of us.’ This then was Currer Bell in person. I need hardly say that I was at once keenly interested, not to say excited. Mr. Williams was called down and introduced, and I began to plan all sorts of attentions to our visitors. I tried to persuade them to come and stay at our house. This they positively declined to do, but they agreed that I should call with my sister and take them to the Opera in the evening.

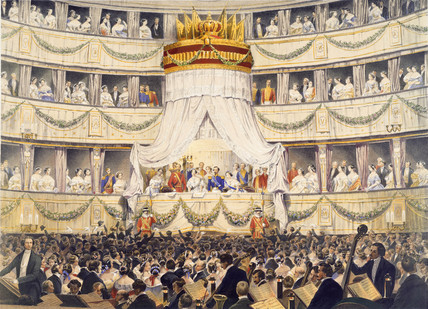

She has herself given an account of her own and her sister Anne’s sensations on that occasion: how they dressed for the Opera in their plain, high-necked dresses: ‘fine ladies and gentlemen glanced at us, as we stood by the box-door, which was not yet opened, with a slight graceful superciliousness, quite warranted by the circumstances. Still I felt pleasurably excited in spite of headache, sickness, and conscious clownishness; and I saw Anne was calm and gentle, which she always is. The performance was Rossini’s Barber of Seville – very brilliant, though I fancy there are things I should like better. We got home after one o’clock. We had never been in bed the night before; had been in constant excitement for twenty-four hours; you may imagine we were tired.’

My mother called upon them the next day. The sisters, after barely three days in London, returned to Haworth. In what condition of mind and body those few days left them is graphically told by Charlotte Brontë herself: ‘On Tuesday morning we left London, laden with books Mr. Smith had given us, and got safely home. A more jaded wretch than I looked, it would be difficult to conceive. I was thin when I went, but I was meagre indeed when I returned, my face looking grey and very old, with strange deep lines ploughed in it – my eyes stared unnaturally. I was weak and yet restless.’

This is the only occasion on which I saw Anne Brontë. She was a gentle, quiet, rather subdued person, by no means pretty, yet of a pleasing appearance. Her manner was curiously expressive of a wish for protection and encouragement, a kind of constant appeal which invited sympathy. I must confess that my first impression of Charlotte Bronte’s personal appearance was that it was interesting rather than attractive. She was very small, and had a quaint old-fashioned look. Her head seemed too large for her body. She had fine eyes, but her face was marred by the shape of the mouth and by the complexion. There was but little feminine charm about her; and of this fact she herself was uneasily and perpetually conscious. It may seem strange that the possession of genius did not lift her above the weakness of an excessive anxiety about her personal appearance. But I believe that she would have given all her genius and her fame to have been beautiful. Perhaps few women ever existed more anxious to be pretty than she, or more angrily conscious of the circumstance that she was not pretty.”

George Smith became not only the publisher but a great friend of Charlotte Brontë, as did his assistant mentioned above W. S. Williams. Charlotte made many more visits to London in the years which followed, and which Smith also details in his fascinating biography. Anne Brontë, alas, would never see London again; in fact this was her one and only journey outside of Yorkshire. She had spent four days in London which transformed literary history for good – and bad. The Brontë name was finally known, and Charlotte and Anne at least got to enjoy some reward for their genius; on the other hand it seems likely that one of the sisters brought something else, other than books, back from London. Tuberculosis, or consumption as it was then known, was a disease spread in crowded places; it was rare in Haworth (Maria and Elizabeth Brontë had contracted it in the confines of a boarding school) but rife in London. Within a year of this four day visit to London, three of the four remaining Brontë siblings had died of tuberculosis.

I hope you enjoy this wonderfully hot and sunny day, no snowstorms expected today, and I hope to see you next Sunday for another new Brontë blog post.