This day in 1817 was surely a day of celebration for Patrick and Maria Brontë. After three girls, Maria, Elizabeth and Charlotte, Maria had given birth to a boy. In the patriarchal society of the time it would have been expected that he would grow up to continue the family name and be the bread winner for the family. He it would be who would bring income to the household and look after his sisters until they could find husbands and homes of their own. He was named after his father, Patrick Brontë, but he became better known by his middle name. Following another tradition of the time, this eldest son was given his mother’s maiden name as a middle name in tribute to her family: Branwell.

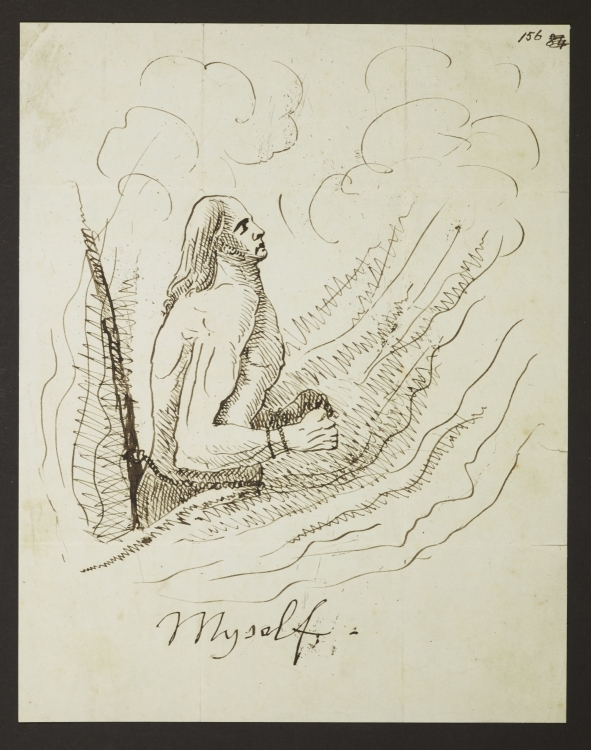

Patrick Branwell Brontë grew up somewhat differently to how his parents may have expected on that auspicious day in Thornton, Bradford 205 years ago. For many years Branwell has lived in the shadows of Charlotte and his two younger sisters Emily and Anne Brontë, or has been depicted as a monstrous figure, an addict who brought misery to his family. Recent years however have seen a re-assessment of Branwell’s life. It was undoubtedly a life of struggle, at least in part because of the terrible early losses of his mother and two eldest sisters. These losses sunk deeply into Branwell and may at least in part have contributed to his troubled adult life. Nevertheless Branwell was not a man without talents; he was a fine poet in his own right, could potentially have become a portrait artist, and was a great raconteur popular with those who knew him in Haworth and beyond. There are now lots of words written about him, but in today’s birthday post we’re going to look at Branwell Brontë in his own words.

Letter to Blackwood’s Magazine of Edinburgh, December 1837

‘SIR, – Read what I write. And would to Heaven you could believe it true, for then you would attend to and act upon it.

I have addressed you twice before, and now I do it again. But it is not from affected hypocrisy that I commence my letter with the name of James Hogg; for the writings of that man in your numbers, his speeches in your ‘Noctes’, when I was a child, laid a hold on my mind which succeeding years have consecrated into a most sacred feeling. I cannot express, though you can understand, the heavenliness of associations connected with such articles as Professor Wilson’s, read and re-read while a little child, with all their poetry of language and divine flights into that visionary region of imagination which one very young would believe reality, and which one entering into manhood would look back on as a glorious dream.

I speak so, sir, because while a child ‘Blackwood’ formed my chief delight, and I feel certain that no child before enjoyed reading as I did, because none ever had such works as ‘The Noctes’, ‘Christmas Dreams’, ‘Christopher in his Sporting Jacket’ to read. And even now, ‘Millions 0′ reasonable creatures at this hour – na’, no at this hour’, etc. or ‘Long, long ago seems the time when we danced hand in hand with our golden-haired sister, whom all that looked on loved. Long, long ago, the day on which she died. That hour so far more dreadful than any hour that now can darken us on this earth, when she, her coffin and that velvet pall descended, – and descended deathlike, and wishing to die, out of the churchyard that from that moment we thought we could never enter more.’ Passages like these, sir (and when that last was written my sister died) – passages like these, read then and remembered now, afford feelings which, I repeat, I cannot describe. But – one of those who roused those feelings is dead, and neither from himself nor yourself shall I hear him speak again. I grieve for his death, because to me he was a portion of feelings which I suppose nothing can arouse hereafter: because to you he was a contributor of sterling originality, and in the ‘Noctes’ a subject for your unequalled writing. He and others like him gave your Magazine the peculiar character which made it famous; as these men die it will decay unless their places be supplied by others like them.

Now, sir, to you I appear writing with conceited assurance: but I am not; for I know myself so far as to believe in my own originality, and on that ground I desire of you admittance into your ranks. And do not wonder that I apply so determinedly: for the remembrances I spoke of have fixed you and your Magazine in such a manner upon my mind that the idea of striving to aid another periodical is horribly repulsive. My resolution is to devote my ability to you, and for God’s sake, till you see whether or not I can serve you, do not so coldly refuse my aid. All, sir, that I desire of you is – that you would in answer to this letter request a specimen or specimens of my writing, and I even wish that you would name the subject on which you would wish me to write. In letters previous to this I have perhaps spoken too openly respecting the extent of my powers. But I did so because I determined to say what I believed. I know that I am not one of the wretched writers of the day. I know that I possess strength to assist you beyond some of your own contributors; but I wish to make you the judge in this case and give you the benefit of its decision.

Now, sir, do not act like a commonplace person, but like a man willing to examine for himself. Do not turn from the naked truth of my letters, but prove me – and if I do not stand the proof, I will not further press myself upon you. If I do stand it, why, you have lost an able writer in James Hogg, and God grant you may gain one in Patrick Branwell Brontë’

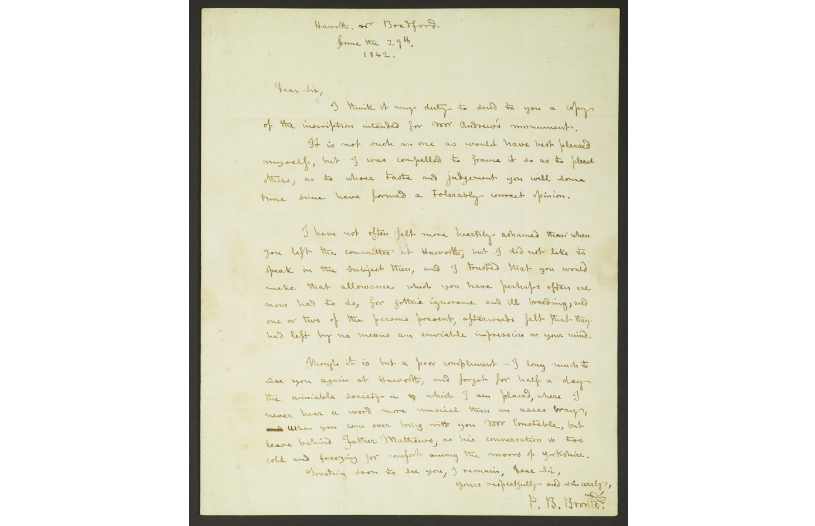

Letter to Joseph Bentley Leyland, June 29th 1842

‘Dear Sir,

I think it is my duty to send to you a copy of the inscription intended for Mr Andrew’s monument.

If it is not such an one as would have best pleased myself, but I was compelled to frame it so as to please others; as to whose taste and judgement you will some time since have formed a tolerably correct opinion. I have not often felt more heartily ashamed than when you left the committee at Haworth; but I did not like to speak on the subject then, and I trusted that you would make that allowance which you have perhaps often ere now had to do, for gothic ignorance and ill breeding; and one or two of the persons present, afterwards felt that they had left by no means an enviable impression on your mind.

Though it is but a poor compliment – I long much to see you again at Haworth, and forget for half a day the amiable society in which I am placed, where I never hear a word more musical than an asses bray; When you come over bring with you Mr Constable, but leave behind Father Matthews; as his conversation is too cold and freezing for the comfort among the moors of Yorkshire.

Trusting soon to see you; I remain, Dear Sir, Yours respectfully and sincerely, P. B. Brontë.’

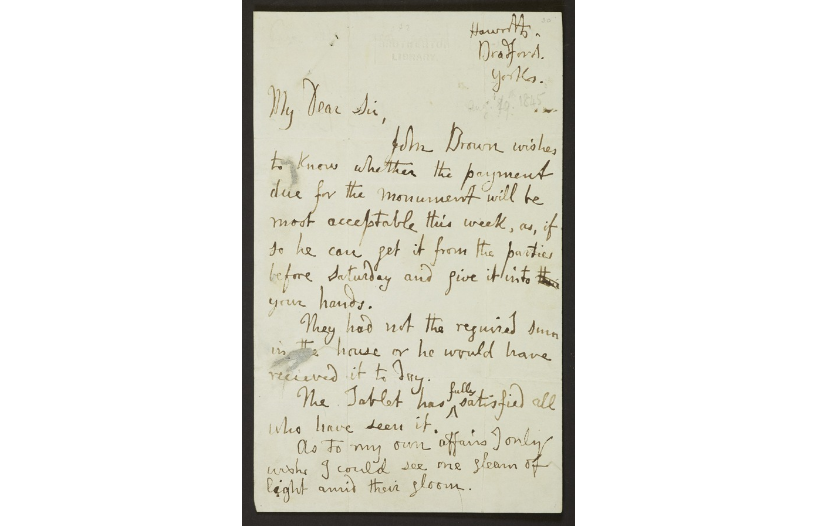

Letter to Joseph Bentley Leyland, August 4th 1845

My dear Sir,

John Brown wishes to know whether the payment due for the monument will be most acceptable this week, as, if so he can get it from the parties before Saturday and give it into your hands.

They had not the required sum in the house or he would have received it to day. The Tablet has satisfied all who have seen it.

As to my own affairs I only wish I could see one gleam of light amid their gloom. You I hope are well and cheerful. Yours sincerely, P. B. Brontë’

Letter to Joseph Bentley Leyland, June 1846

‘Dear Sir,

I should have sent you “Morley Hall” ere now, but I am unable to finish it at present from agony to which the grave would be far preferable.

Mr Robinson of Thorp Green is dead, and he has left his widow in a dreadful state of health, she sent the Coachman to me yesterday, and the account which he gave of her sufferings was enough to burst my heart. Through the will she is left quite powerless, and her eldest daughter who married independently, is cut off without a shilling.

The Executing Trustees detest me, and one declares that if he sees me he will shoot me. These things I do not care about, but I do care for the life of the one who suffers even more than I do. Her Coachman said that it was a pity to see her, for she was only able to kneel in her bedroom in bitter tears and prayers. She has worn herself out in attendance on him, and his conduct during the few days before his death, was exceedingly mild and repentant, but that only distressed her doubly. Her conscience has helped to agonize her, and that misery I am saved from.

You, though not much older than myself, have known life. I now know it was a vengeance – for four nights I have not slept – for three days I have not tasted food – and when I think of the state of her I love best on earth, I could wish that my head was as cold and stupid as the medallion that lies in your studio.

I write very egotistically but it is because my mind is crowded with one set of thoughts, and I long for one sentence from a friend. What I shall do I know not – I am too hard to die, and too wretched to live. My wretchedness is not about castles in the air, but about stern realities; my hardihood lies in bodily vigour; but, Dear Sir, my mind sees only a dreary future which I as little wish to enter on, as could a martyr to be bound to the stake.

I sincerely trust that you are well, and hope that this wretched scrawl will not make me appear to you a worthless fool, or a thorough bore.

Believe me, Yours, most sincerely, P B Brontë.’

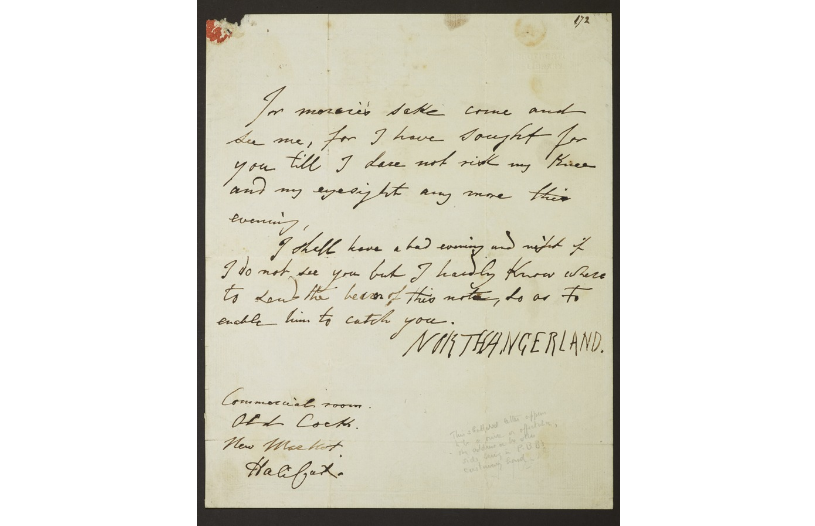

Branwell Brontë to Joseph Bentley Leyland, 16th July 1847 (sent from the Old Cock Inn, Halifax)

‘For mercies sake come and see me, for I have sought for you till I dare not risk my knee and my eyesight any more this evening, I shall have a bad evening and night if I do not see you but I hardly know where to send the bearer of this note, so as to enable him to catch you.

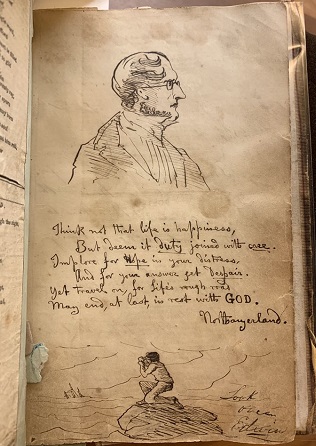

NORTHANGERLAND.’

Letter to Francis Grundy, 1848

‘Dear Sir,

I fear you will burn my present letter on recognizing the handwriting, but if you will read it through you will perhaps rather pity than spurn the distress of mind which could prompt my communication after a silence of nearly three (to me) eventful years.

While very ill, and confined to my room, I wrote to you, two months ago, directing my letter to either the principal Inn in Bingley or Keighley, because I did not know your proper address; and as I heard you were engaged on the Bradford extension line I concluded that in your surveys you would have occasion to take your quarters at times in either of the two houses. I never heard from you in reply and as my letter only asked for one day with you to ease a very wearied mind in the company of a gentleman who use to have what I wanted always, but most want now – cheerfulness – I am sure you never received my letter or your generous heart would have prompted an answer.

When I say that since I last shook hands with you in Halifax two summers ago my life till lately has been one of apparent happiness and indulgence you will ask why should I now complain? And I can only reply by shewing the under current of distress that bore my bark toward a whirlpool despite the surface waves of life that seemed wafting me toward peace.

In a letter begun in the spring of 1848 and never finished owing to incessant attacks of illness I tried to tell you how I was situated. As Tutor to the only son of a wealthy gentleman whose wife was sister to Mr Thomas Gisborne M.P. for Nottingham, Mrs Evans the wife of the member for one division of Derbyshire and the cousin of Mr. Macaulay. This lady (though her husband detested me) shewed toward me a degree of kindness which;when I was deeply grieved one day at her husband’s conduct towards me; opened into an unexpected declaration of more than ordinary feeling. My admiration of her mental and personal attractions which, though she is 17 years older than myself, are both very great, my knowledge of her totally unselfish generosity, sweet temper and unwearied care for all others with ill requital in return. My horror at the heartless and unmanly manner in which she was treated by an eunuch like fellow who though possessed of such a treasure never even occupied the same apartment with her. All combined to make me reciprocate an attachment I had little dared to look for. During nearly three years I had daily “Troubled pleasure soon chastised by fear” in the society of one whom I must, till death, call my wife.

Three months since, while at home, I received a furious letter from my Employer threatening to shoot me if I returned from the vacation- and letters from her ladies maid and her physician informed me of the outbreak and threatened proceedings only checked by her firm courage and resolution that come what might harm might to her none should come to me. The wretchedly broken health and want of energy in her bloodless mock husband made him put up with the simple joy of daily torturing her while I was left uninjured.

Had I strength to return and meet him the results would be serious to one or both, but providence has hitherto denied me this power for I have lain during nine long weeks utterly shattered in body and broken down with mental despair. The probability of his state of health ere long leaving her free to give me herself and her estate as was her hearts resolve never rose to drive off the prospect of her decline under her present grief and sufferings and I dreaded too the wreck of my mind and body which God knows have both during a short life been severely tried.

Eleven continued nights of sleepless horrors reduced me to almost blindness and while taken into Wales to rouse me the sweet scenery, the sea, the sound of music only caused fits of unspeakable distress and irrepressible tears. I implored for society and comfort but could neither be pleasant to one or pleased by the other, and wine or other stimulants only caused not exhilaration but deeper dejection.

You will say “What a fool!” but if you knew the many causes I have had for sorrow which I cannot hint at here you would pity as well as blame. I am better now but though at the kind request of Mr Macaulay and Mr Baines I have striven to rouse my mind by writing something that I ought to make deserving of being read, I find I really cannot yet do so with effect for one line of poetry like one note of music produces in my frame a sickening thrill of despair.

I know you will – if you read it at all – despise this letter and its writer, but I can only answer the writer does the same, and he would not wish to live if he did not hope that active exertion and change of scene may yet restore him to the by past manhood which used to boast of unconquerable health, where for 3 year he has known no interval of one week from agonizing sickness, and latterly not even one day.

I should indeed be gratified if I knew that you would soon be anywhere where an hours visit to you would not be forbidden. The crumpled appearance of the sheet is owing to my having kept it unfinished for days in my pocket.

Apologising sincerely for what will seem whining egotism and hardly daring to hint about days when in your company I could sometimes laugh or smile the thoughts of which “Remind me of departed times” but, I would fain hope, not “Departed never to return.”

I remain, Dear Sir, Yours most sincerely, P.B.Brontë.’

These letters show the sad journey of Branwell Brontë from confidence and hope to complete and utter despair, but through it all he had friends. Despite this latter letter, Grundy did not in fact despise the letter and its writer; from his biography ‘Pictures of the Past’ it is clear that Grundy loved and esteemed Branwell Brontë. Upon receiving the letter Grundy made his way to Haworth and met Branwell at the Black Bull Inn, giving a terrible picture of Branwell in his ultimate decline. He found him shaking and stooped, and Branwell drew out a knife revealing that he was worried that it was Satan coming to visit him, and he’d intended to run him through.

We cannot help but be moved by Branwell Brontë’s letters and the terrible progression they show. Yet those who knew him well, from sculptor Joseph Bentley Leyland to railway surveyor Francis Grundy held him always in the highest regard, and there can be no doubt that for all his troubles his sisters loved him dearly too. We’ve seen Branwell Brontë through his own words today, but let’s leave the final word to Francis Grundy who summed him up very neatly: “Patrick Branwell Brontë was no domestic demon – he was just a man moving in a mist, who lost his way.”

On his 205th anniversary let’s remember the loving brother, the man devoted to the woman he had loved, the skilful poet and artist, the kind friend, the man who could write two separate letters with both hands at the same time. I hope you can join me next week for another new Brontë blog post. Happy birthday Branwell Brontë.

Thank you for writing about Branwell Brontë & so sympathetically. I have long felt much sympathy for him, the woman he loved, a real life Mrs. Robinson who was very far from the suffering angel he thought her to be, even her own daughters stopped speaking to her. She played Branwell & in doing so, all but destroyed him. His reputation wasn’t helped by his sister Charlotte & also Mrs. Gaskell. I’ve read his poetry & it’s as good, if not better, than his more famous sisters, particularly Charlotte, it’s a great pity that the character destruction, of which he was victim, has resulted in nobody showing much interest in his work. I expect you’re already familiar with the book (in two volumes) written by Francis A. Leyland, “The Brontë Family with Special Reference to Patrick Branwell Brontë, if not, it is well worth your time to read it, being written by Frances, the brother of Joseph Bentley Leyland. He was able to interview many who had actually known Branwell which increases the interest in this work.

I really enjoy all your posts about the Brontë family & long may you continue to write them.

Reading his letter, it’s no wonder his memory is obscure. Worst of Victorian hubris & obfuscation. In pacem etc.