Charlotte Brontë and her sisters were among the greatest writers of the Victorian era, and many would select Charlotte Brontë’s Jane Eyre as the greatest novel of the century. In their own lives, however, we can see that the Brontë siblings were influenced by the societal norms of the time, but they were far from bound by them. In today’s post we’re going to look at one word which Charlotte Brontë certainly possessed, although many at the time would have thought that to be entirely unbefitting to a woman: passion.

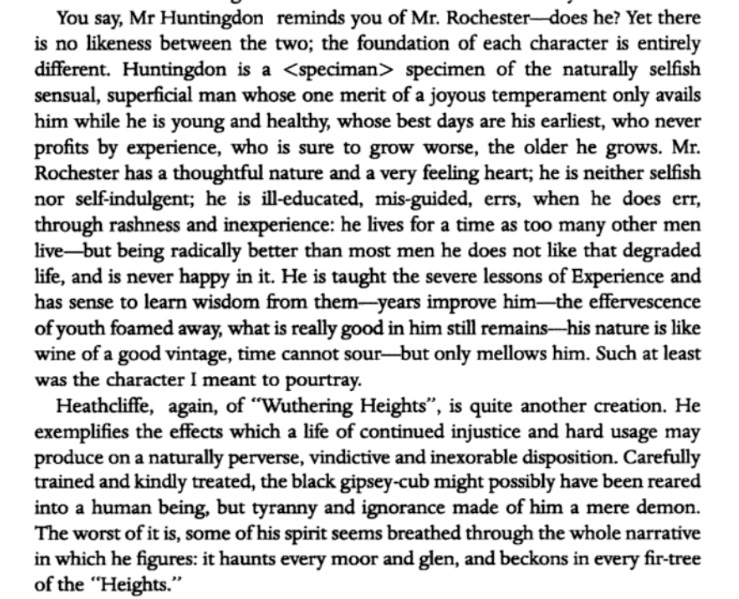

Only a genius could have written Jane Eyre, but only a special kind of genius: one who knew the power of longing, the driving force of passion. One reason for the novel’s great success is its protagonists. Rochester is not a typical romantic hero, but nor is he a pantomime villain. It is this complexity which makes him compelling and believable, and which Charlotte elucidated upon in a letter sent to W. S. Williams at her publisher:

Rochester, at least as far as his creator is concerned, is a man both sinned against and sinning; he made mistakes in his youth but atones for them in his adulthood. He has made mistakes but atones for them. The great thing about the novel, and about any great novel, is that readers are free to make their own judgements on the character.

What is clear is that Rochester was highly influenced by a man who had been in Charlotte’s own life: Constantin Heger. A powerful man with undoubted faults, but whose personality drew Charlotte inexorably to him, just as Rochester does to Jane. Charlotte’s letters to Monsieur Heger after leaving Brussels are incredibly sad as we know that he never responded to them – they are also incredibly passionate, as in this extract from a letter dated 18th November 1845:

‘In a word, tell me what you will, my master, but tell me something. Writing to a former assistant teacher (no – I don’t want to remember my position as an assistant teacher, I disown it) well then, writing to an old pupil cannot be a very interesting occupation for you – I know that – but for me it is life itself. Your last letter has sustained me – has nourished me for six months – now I need another and you will give it me… To forbid me to write to you, to refuse to reply to me – that will be to tear from me the only joy I have on earth… when day after day I await a letter and day after day disappointment flings me down again into overwhelming misery, when the sweet delight of seeing your writing and reading your counsel flees from me like an empty vision – then I am in a fever – I lose my appetite and sleep – I pine away.’

In an earlier letter to Heger (24th July 1844), Charlotte had written of the driving force behind her writing dream:

‘My sight is too weak for writing – if I wrote a lot I would become blind. This weakness of sight is a terrible privation for me – without it, do you know what I would do, Monsieur? I would write a book and I would dedicate it to my literature master – to the only master that I have ever had – to you Monsieur.’

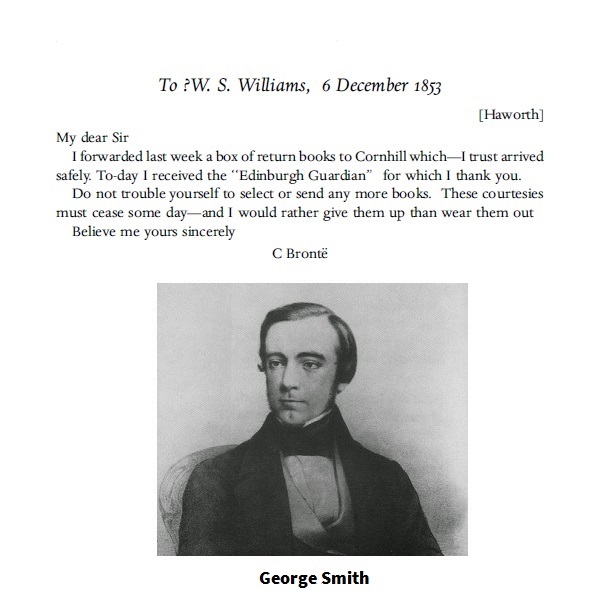

Alas for Charlotte, Heger, like Rochester, was already married, but there was to be no happy ending for the lovelorn woman in Haworth. Without Heger would there have been a Rochester, or a Paul Emanuel in Villette, would there have been any Charlotte Brontë novels? Probably not. The publication of Jane Eyre transformed Charlotte’s life, and the lives of readers ever since, but it also brought her into contact with another man she developed a passion for: George Smith.

Smith was younger then Charlotte, and from a very different background: he had inherited his father’s publishing business of Smith, Elder & Co at a young age, and was both wealthy and well connected, not to mention handsome.

George Smith became more than a publisher to Charlotte Brontë, he became a close friend. Charlotte was often invited to visit him in London, and they even holidayed in Scotland together. He frequently sent a supply of books to Haworth for Charlotte to read (an expensive commodity at the time), but on 6th December 1853 Charlotte wrote a sad, short letter to the publishing house saying that she wished to receive no more:

A month earlier Charlotte had heard the news that George Smith had become engaged to an Elizabeth Blakeway and she was once more heartbroken. Four months later Charlotte finally accepted the suit of Arthur Bell Nicholls and became engaged herself, but despite short lived attempts at starting new work she wrote no more for Smith, Elder & Co.

Charlotte’s passionate nature was at the heart of her creative genius, and for that we can all be thankful. I hope you can join me next week for another new Brontë blog post, but for now I leave you with a poem that Charlotte Brontë wrote on this day in 1841. It’s title? ‘Passion’.