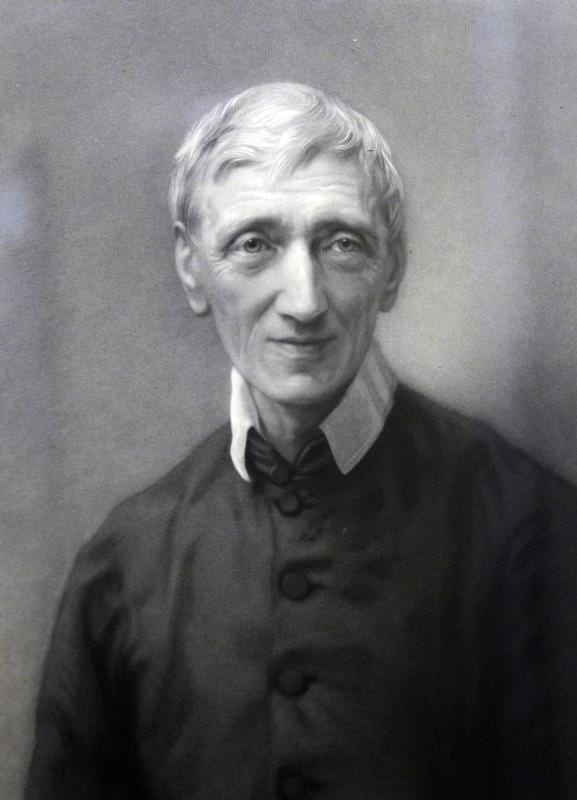

This is a special day for many in Britain, as today in the Vatican Pope Francis I is canonising John Henry Newman – better known as Cardinal Newman, but from today called Saint John Henry Newman. It’s particularly historic as he is the first British person to be made a Saint in 43 years, and he is the first ‘modern’ Brit to gain that honour as our previous most recent saint lived in the 17th century. He is of interest to this blog for his connection to Charlotte Brontë, so we’ll take a brief look at St. John (no, not St. John Rivers on this occasion), at how Charlotte knew him and why it’s strange that Charlotte should have felt such an affinity to his teachings.

Part of Newman’s great appeal is that he in many ways seems an ordinary person, for a saint. He is a man that it’s easy to relate to, and also one that unites faiths. He was born in 1801 in London and was to become a towering figure in nineteenth century theology. For a Catholic Saint, however, it is perhaps surprising that he was born into a Protestant family and his mother Jemima (formerly Jemima Fourdrinier) was of a Huguenot refugee family who, like many other Huguenots (French Protestants) had had to flee France in fear of their lives and after persecution from the Catholic church there.

As a child Newman impressed as a scholar, and he particularly loved to read the novels of Walter Scott – just as the Brontës did. At age 15, another strange event occurred for a man who would be canonised, as he became a convert not to Catholicism but to Calvinism. Calvinism was the hardline branch of Protestantism, whose proponents believed in the elect and the damned. If you were elect, you would be pre-destined to heaven, whatever you did on earth. All others, however, were destined to the eternal torments of hell if they sinned once. Unsurprisingly, most Calvinist preachers recognised themselves as the elect and their parishioners as the damned.

It was a harsh doctrine that despised Catholicism and denounced the Pope as the anti-Christ. They preached of punishment and hellfire, and a perfect example of a Calvinist was Reverend William Carus Wilson, who ran the Clergy Daughter’s School which tragically claimed the lives of the two eldest Brontë sisters Maria and Elizabeth. Charlotte revenged herself upon Wilson, and Calvinists in general, by depicting him as the cruel Mr. Brocklehurst in ‘Jane Eyre‘, and Anne Brontë also attacked them in a poem which she entitled, ‘A Word To The Calvinists’ and which was later changed to ‘A Word To The Elect’. In its opening we see Anne take aim at their hypocrisy and hit the target:

‘You may rejoice to think yourselves secure;

You may be grateful for the gift divine –

That grace unsought, which made your black hearts pure,

And fits your earth-born souls in Heaven to shine.

But, is it sweet to look around, and view

Thousands excluded from that happiness,

Which they deserved, at least, as much as you, –

Their faults not greater, nor their virtues less?’

Newman, then, had become a proponent of the most fervently anti-Catholic sect of them all, and in 1825 he took holy orders and was ordained a priest in the Church of England, one who still held Calvinist views. Rather than becoming a parish priest, however, he became an Oxford academic (and de facto priest of the University’s St. Mary’s church), preacher and theologian and gradually over the next decade his views began to change. He wrote on the need to find common ground between Anglicanism and Catholicism, the ‘middle way’ that he gave a series of popular lectures on.

By 1842, with his views causing increasing controversy in the church, Newman had retreated from University life and created an Anglican monastery (it’s now Oxford’s Newman College), but he had embarked upon a path that would change his life.

In 1843 he resigned from his post at St. Mary’s and published an advertisement in an Oxford paper retracting and apologising for his previously stated views on Catholicism. In 1845 the progression was completed as Newman was formally received into the Roman Catholic church, and a year later was ordained a Catholic priest. He now embarked on a further series of lectures in London and Birmingham called ‘The Present Position of Catholics in England’. In these lectures he denounced the anti-Catholic sentiment that was high in the country at that time, and the aggressive measures taken against Catholics.

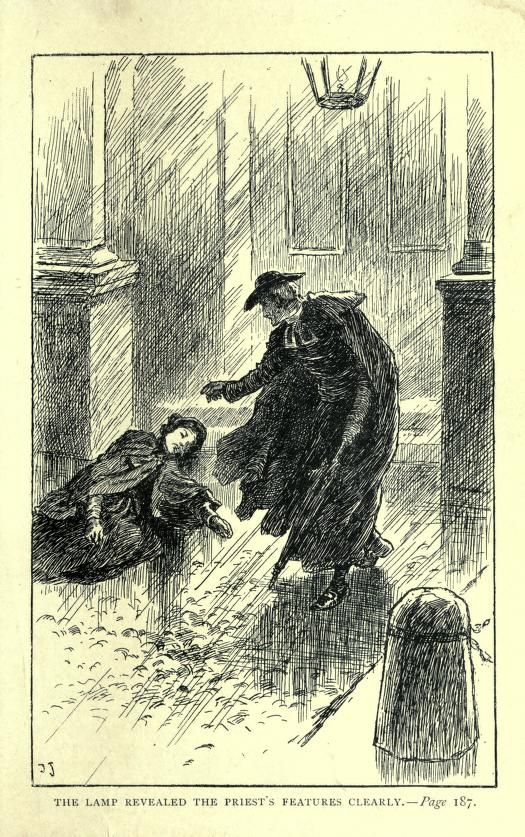

During one such lecture Newman was said to have libelled a former Catholic who now vehemently preached against the faith, and he was arrested and expected to receive a prison sentence. Newman was found guilty, but escaped prison with a £100 fine and an admonishment from the judge about his ‘moral deterioration’ after his conversion to Catholicism. Newman’s response was ‘posterity shall be my judge’.

Newman’s notoriety increased, and he produced a series of works which sold in large numbers, as well as addressing large crowds wherever he went. In 1879 he was made a Cardinal of the Catholic Church, but as always he defied convention by not being a Bishop first and by refusing to be a Bishop once elevated to the Cardinal rank. It was also usual then for Cardinals to live in Rome, but the now Cardinal Newman insisted on remaining in Birmingham.

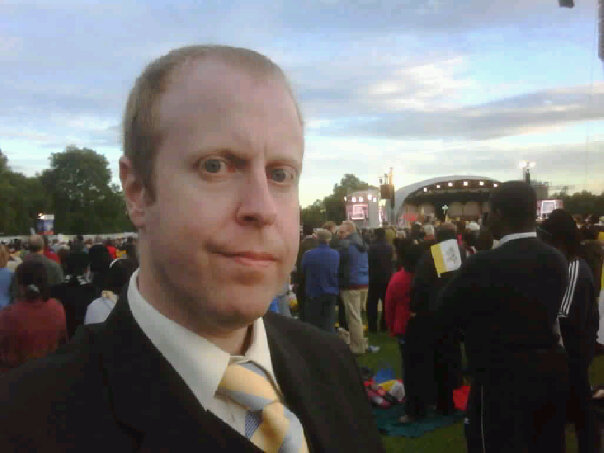

When Newman died in 1890 the nation mourned, and in the century and more that has followed increasingly people saw him as a figure of devotion. Miracles were attributed to him, and it is this that led to his beatification by Pope Benedict XVI in 2010. I was one of many tens of thousands of people who filled Hyde Park to see the Pope celebrate this beatification, and it was an incredibly moving event. Nine years later, after a further miracle was officially recognised by the church, he has been given the ultimate accolade of Sainthood.

Newman was known across Britain and beyond throughout the nineteenth century. He was a passionate and brilliant speaker, and we know that one person who attended his lectures was none other than Charlotte Brontë. The lectures she saw were in London in 1850, and were tellingly entitled ‘Certain Difficulties Felt By Anglicans In Submitting To The Catholic Church’. She later told Elizabeth Gaskell about them, who reported in a letter to Catherine Winkworth:

‘Miss Brontë agreed with me in liking Mr. Newman’s Soul, and in liking Modern Painters, and the idea of the Seven Lamps; and she told me about Father Newman’s lectures at the Oratory in a very quiet, concise, graphic way.’

It at first seems strange that Charlotte should profess such an admiration for Newman, and to attend his lectures, as some of her works express profound anti-Catholic sentiment. This was merely in common with many of the people at the time, but it can still be hard to read ‘The Professor’ particularly, with its passages such as:

‘I long to live once more among Protestants; they are more honest than Catholics; a Romish school is a building with porous walls, a hollow floor, a false ceiling; every room in this house, monsieur, has eyeholes and ear-holes, and what the house is, the inhabitants are, very treacherous; they all think it lawful to tell lies; they all call it politeness to profess friendship where they feel hatred.’

Nevertheless, Charlotte was attracted to Newman, and possibly even to Catholicism itself. One startling scene in ‘Villette’ sees Lucy Snowe heading in despair to a confessional in the Roman Catholic cathedral, and we know that Charlotte, in despair at her unrequited love for M. Heger, followed exactly the same course on 1st September 1843 in the grand St. Gudule’s Cathedral. She disclosed this to Emily, her confessor of a different kind:

‘An odd whim came into my head. In a solitary part of the Cathedral six or seven people still remained kneeling by the confessionals. In two confessionals I saw a priest. I felt as if I did not care what I did, provided it was not absolutely wrong, and that it served to vary my life and yield a moment’s interest. I took a fancy to change myself into a Catholic and go and make a real confession to see what it was like. Knowing me as you do, you will think this odd, but when people are by themselves they have singular fancies… I actually did confess – a real confession… I think you had better not tell Papa of this. He will not understand that it was only a freak, and will perhaps think I am going to turn Catholic.’

Was this a ‘freak’ as she called it, or was it something that deep down she had considered for a while and continued to consider? Was she considering it when she went to watch John Henry Newman deliver his lecture about Anglicans submitting to the Catholic church? I think it shows that Charlotte was at heart not bigoted against Catholics, and in fact not bigoted in any way at all. She was always looking to understand people, to find a Newman-like ‘middle way’.

Newman, like the Brontës, was also a keen poet. His most famous work is ‘The Dream Of Gerontius’. That’s a long, complex poem so I leave you with his poem ‘The Trance Of Time’, as we say thank you Saint John Henry Newman for showing us the importance of loving and understanding one another, whether we have faith, of any kind, or not:

‘In childhood, when with eager eyes

The season-measured year I view’d,

All garb’d in fairy guise,

Pledged constancy of good.

Spring sang of heaven; the summer flowers

Bade me gaze on, and did not fade;

Even suns o’er autumn’s bowers

Heard my strong wish, and stay’d.

They came and went, the short-lived four;

Yet, as their varying dance they wove,

To my young heart each bore

Its own sure claim of love.

Far different now; – the whirling year

Vainly my dizzy eyes pursue;

And its fair tints appear

All blent in one dusk hue.

Why dwell on rich autumnal lights,

Spring-time, or winter’s social ring?

Long days are fire-side nights,

Brown autumn is fresh spring.

Then what this world to thee, my heart?

Its gifts nor feed thee nor can bless.

Thou hast no owner’s part

In all its fleetingness.

The flame, the storm, the quaking ground,

Earth’s joy, earth’s terror, nought is thine,

Thou must but hear the sound

Of the still voice divine.

O priceless art! O princely state!

E’en while by sense of change opprest,

Within to antedate

Heaven’s Age of fearless rest.’

![]()

A very enlightening article.

Thank you! I found this interesting and helpful.