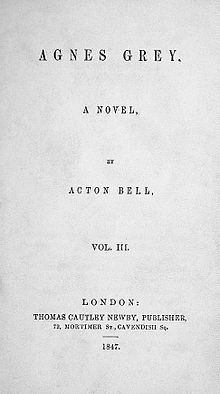

This week was a particularly exciting one for two members of the Brontë household in 1847, for on 4th July of that year Emily and Anne Brontë sent the manuscripts of their first novels to their publisher. The novels were ‘Wuthering Heights‘ and ‘Agnes Grey‘ respectively, and the publisher was the London firm of Thomas Cautley Newby, but just who was he and was he reputable?

Anne and Emily must have been delighted to receive an offer from Newby, after receiving a succession of terse rejection notes from other publishers, but their immediate joy would have been tempered for two reasons: firstly, Charlotte had failed to find a publisher for her work, ‘The Professor’, and secondly Newby had stated that the sisters would have to pay him an upfront sum of £50. This was a considerable amount of money, two years salary on a typical governess wage, but, using money left to them by their Aunt Branwell, they paid and on that July day sent the completed and corrected manuscript proofs to him.

After this they waited, and waited, but there seemed little sign of the books actually being released. So slow was the process that Charlotte not only managed to write another book but have it published before the works of ‘Ellis’ and ‘Acton’ Bell saw the light of day. It seems that it was the success of Charlotte’s book, Jane Eyre of course, that spurred Newby into finally releasing the novels that he held, realising that he could cash in on the overnight success of what he presumed was a brother of the two authors he’d signed up. Newby was a shrewd marketer with an eye for a profit, for himself at least, but what else was he?

Founding his firm in 1843, Newby became known for discovering and publishing debut novels by new authors, and the Brontës weren’t the only ‘find’ of his that has gone on to take a place in the literary pantheon, as in this same year 1847 he also published a first novel called ‘The Macdermots of Ballycloran’; its author? Anthony Trollope.

Newby finally published ‘Wuthering Heights’ and ‘Agnes Grey’ in December 1847, but when they received their six author copies, Emily and Anne were dismayed to see that the errors they had diligently corrected in the proofing process had remained in the finished and printed works.

By November 1847 it was already clear that all three sisters were concerned about Newby’s methods as we see in a letter from Charlotte to W. S. Williams who worked for her publisher:

‘A prose work by Ellis and Acton will soon appear: it should have been out, indeed, long since; for the first proof sheets were already in the press at the commencement of last August, before Currer Bell had placed the M.S. [manuscript] of ‘Jane Eyre’ in your hands. Mr. Newby, however, does not do business like Messrs. Smith and Elder, a different spirit seems to preside at 72 Mortimer Street to that which guides the helm at 65 Cornhill. Mr. Newby shuffles, gives his word and breaks it… my relatives have suffered from exhausting delay and procrastination… I should like to know if Mr. Newby often acts as he has done to my relatives, or whether this is an exceptional instance of his method?’

The ever perceptive Charlotte already had the measure of her sisters’ publisher, for this was indeed his method – along with his other favoured tactic of obfuscation and downright lies, as the family were to find out to their cost in July 1848.

The story is now well known of how Newby had been telling an American publisher that all three ‘Bell’ brothers were the same person, and that his new work for sale, Anne’s second novel ‘The Tenant Of Wildfell Hall’ was actually by the author of the acclaimed ‘Jane Eyre’. When Charlotte’s publisher Smith, Elder & Co. heard of this they wrote to ‘Currer’ for clarification and this led to Charlotte and Anne travelling to London to clear up the mystery, finally revealing their true identity. The terrible downside of this was that on their return to Haworth it seems likely that one of them brought back a strain of tuberculosis then endemic in London, and which would reduce the four siblings to one within a year.

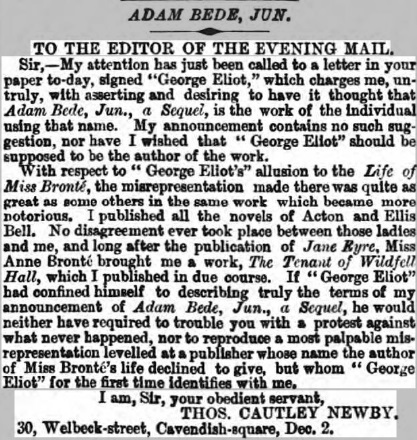

Newby’s other con tricks involved bringing out sub standard ‘sequels’ to best selling books, fooling the public into wrongly thinking the original author had produced a new work. One such author insulted in this way was George Eliot who protested strongly when Newby announced that he was about to publish ‘Adam Bede, Junior, A Sequel’. Newby, in the manner of habitual liars before and since, broke out in indignant anger, writing to the Evening Mail of London to defend his name on 5th December 1859. This letter is particularly interesting to us, for in it he gives direct comments on his relations with Anne Brontë, as he saw them at least:

‘Sir – my attention has just been called to a letter in your paper to-day, signed “George Eliot”, which charges me, untruly, with asserting and desiring to have it thought that Adam Bede, Jun., a Sequel, is the work of the individual bearing that name. My announcement contains no such suggestion, nor have I wished that “George Eliot” should be supposed to be the author of the work.

With respect to “George Eliot”s’ allusion to the Life Of Miss Brontë, the misrepresentation made there was quite as great as some others in the same work which became more notorious. I published all the novels of Acton and Ellis Bell. No disagreement ever took place between those ladies and me, and long after the publication of Jane Eyre, Miss Anne Brontë brought me a work, The Tenant Of Wildfell Hall, which I published in due course. If “George Eliot” had confined himself to describing truly the terms of of my announcement of Adam Bede, Jun., a Sequel, he would neither have required to trouble you with a protest against what never happened, nor to reproduce a most palpable misrepresentation levelled at a publisher whose name the author of Miss Brontë’s life [Elizabeth Gaskell] declined to give, but whom “George Eliot” for the first time identifies with me. I am, Sir, your obedient servant, Thomas Cautley Newby, 30, Welbeck-Street, Cavendish-square’

As always we do well not to take Newby at his word, especially as he seems to labour under the impression that George Eliot, real name Mary Anne Evans, is a man. I think it’s fair to say that his dealings with Anne and Emily were rather less honest than he implies too, although it remains a mystery as to why Anne published her second novel with him rather than switching to Charlotte’s exemplary publisher, as the elder sister had suggested.

Trollope received no money from Newby for his debut novel, and that fate would surely have befallen Emily and Anne too, if Charlotte’s publisher George Smith hadn’t spoken directly to Newby about it, resulting in him finally sending a cheque of £90 for royalties – alas too late, the authors by that time were dead.

Despite his protestations of innocence, Newby also had to admit defeat in his battle against George Eliot, and the Adam Bede sequel was never published. He continued to follow the same antics with other big names, however, including Anthony Trollope, and he was as notorious and untrustworthy a publisher as could be found until he finally stopped his presses in 1874. Anthony’s mother Fanny Trollope was a hugely popular novelist at the time (although Charlotte once called her books a ‘ridiculous mess’) and she too fell victim to Newby’s ways after he brought out a series of books by an in house novelist called simply ‘F. Trollope’ – no doubt, as in his letter addressing George Eliot above, Newby would have protested that he was making no suggestion that the books were by Fanny.

He was a scoundrel and a cad, but it seems to me that if he hadn’t decided to make an easy fifty pounds from Ellis and Acton Bell, the likelihood is that the sisters would have exhausted all of their contacts and become finally discouraged; without Thomas Cautley Newby, then, and all his insincerities, cons and tricks, it seems highly possible that there would be none of the Brontë novels we love today.

Thanks for this.

I suspect Anne stuck with Newby because she had a kind and forgiving nature!

He was a bit of a swindler, but as you point out, perhaps the world would not know the name of Bronte if they hadn’t dealt with him.

In any event, I’m glad that we do have their novels to enjoy and learn from!