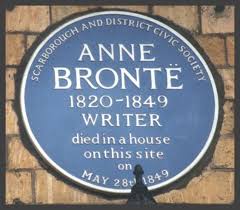

On this day, May 28th, in 1849 a young woman in her twenties was dying in a room in lodgings taken at Scarborough, with her sister Charlotte and friend Ellen looking hopelessly on. She died in obscurity, even though her latest novel ‘The Tenant Of Wildfell Hall’ had recently become a celebrated novel under the pseudonym of Acton Bell. Yet now, 167 years after the death of Anne Brontë, we can give her the praise that she deserves for her talents as a writer, and for her great courage and humanity.

Anne’s health had been deteriorating for many months, and after the passing of her beloved sister Emily five months earlier it was clear that Anne too was dying of consumption, or tuberculosis as we call it now. It seems likely that Anne had carried tuberculosis within her since her early childhood, but the visit to London in the summer of 1848 had exposed her to massive doses of tubercular pathogens that she then brought back to the Haworth Parsonage with devastating consequences.

Unlike Emily, who refused to see a doctor until the day of her death, Anne sought to prolong her life if possible. She tried every remedy suggested, although complained that one medicine tasted like train oil, and had to desist from taking it because it made her sick. By May 1849 she was incredibly emaciated. We know from the account of William Wood, Haworth’s coffin maker, that Emily Brontë, despite being unusually tall for her time, was buried in the thinnest adult coffin he had ever made – measuring just seven inches across. Charlotte reported that Anne had become even thinner than Emily.

Nevertheless, Anne wanted to try one last thing – she wanted to go to Scarborough, famed for the healing waters of its spa. Did Anne really believe that the waters could cure her (she had after all spent many summers in the resort and seen others ‘taking the waters’)? Did she want to see her beloved Scarborough one last time? Or was it simply that she wanted to spare her father Patrick the onerous duty of burying the third of his children in nine months? Quite probably, it was a combination of all three, and so it was that on May 25th the three young women arrived at Wood’s Lodgings in Scarborough, the respectable lodging house previously used by Anne when she was with the Robinson family. The Grand Hotel now stands on the site.

Anne had recently received a bequest from her Godmother Fanny Outhwaite, and she used the money from this to pay for the journey for herself, Charlotte, and Ellen and also to pay for a ticket that allowed them unlimited access to the Spa and the newly built Cliff Bridge linking it to Wood’s Lodgings.

In Scarborough, Anne revived a little, although her breathing was very bad. She took a donkey ride across the sands, insisting on driving the animal herself so that it wouldn’t be mistreated. Here, on the beach, she asked Charlotte and Ellen to be alone. She had a lifetime of thinking to do, and only days or hours to do it in. This, after all, was the very beach she had chosen for the denouement to Agnes Grey. Here was the spot on which she had turned around and found her love Edmund Weston waiting for her. Did she know feel the real Weston, William Weightman, drawing closer to her?

After an hour, Anne drove the donkey back, all was now done that needed to be done.

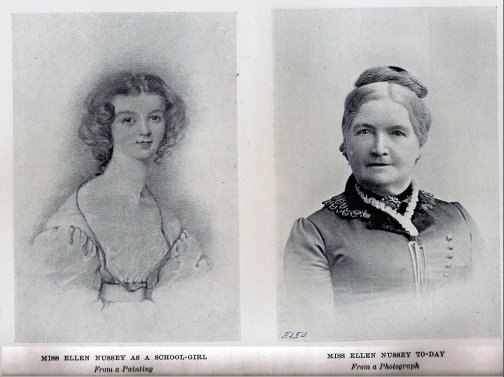

On Sunday May 27th, Anne asked to be taken to the church, but Charlotte gently explains that this is out of the question. She then tells her companions to go, but they won’t leave her. That evening, as Ellen explained in a beautiful booklet she wrote entitled ‘ A Short Account Of The Last Days Of Dear A.B.’, there came ‘the most glorious sunset ever witnessed’. There was a golden sky filled with sunbeams, a boat bobbed on the ebbing tide, and they had moved Anne to the window to look down at it. Here, to my mind, is a replica of Anne’s picture of a decade earlier ‘Sunrise Over Sea’. What she had pictured as a woman looking out at a sunrise at the start of her adult life, had become a woman looking at a sunset at the end of it.

The next day, Whit Monday, Anne had to be carried down the stairs by Ellen. At one point their heads clashed and Anne slumped forward. A horrified Ellen thought she had killed her friend, but Anne revived and said: ‘don’t be sorry, you did your best.’ She was then placed on a sofa that she would never rise from again.

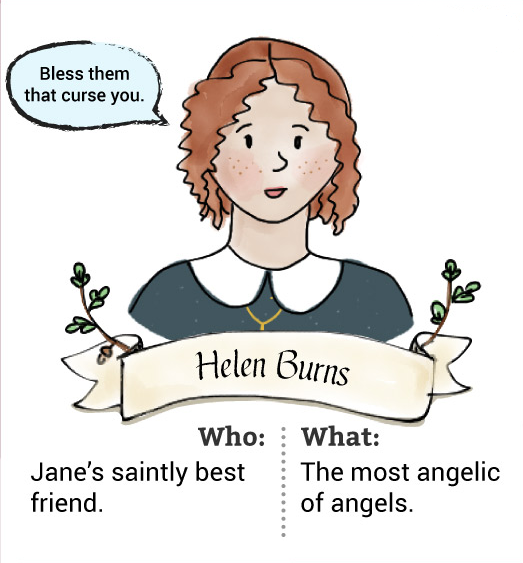

A doctor was called for and pronounced that Anne had only hours to live, but Anne remained calm and collected throughout. She was not scared to go, although she asked Ellen to be like a sister to Charlotte in her absence; she called upon her faith, and in this final test it was not found to be lacking. Her last words, as recorded by Ellen, were spoken to Charlotte:

‘Take courage, Charlotte, take courage!’

The doctor later said that he had never seen such a gentle death, and a sign of its tranquillity is that tea was brought in to their rooms shortly after 2pm when Anne had taken her final breath.

This is inevitably a day of sadness, after all a great writer was taken from us aged just 29 when she had so much more to say and give. But, we should look at the joy she has given us and follow her final command, to take courage. This is a good day to give thanks for Anne Brontë, and read one of her books or poems, this woman of truth, beauty, and courage.