Halloween is a special time in Haworth as the village decks itself out in spooky regalia and people come from far and wide to watch its Parade of Ghouls and Parade of the Dragon. We all love a scary story, and of course three women who bring all the tourists to Haworth, the Brontë sisters, were no exception.

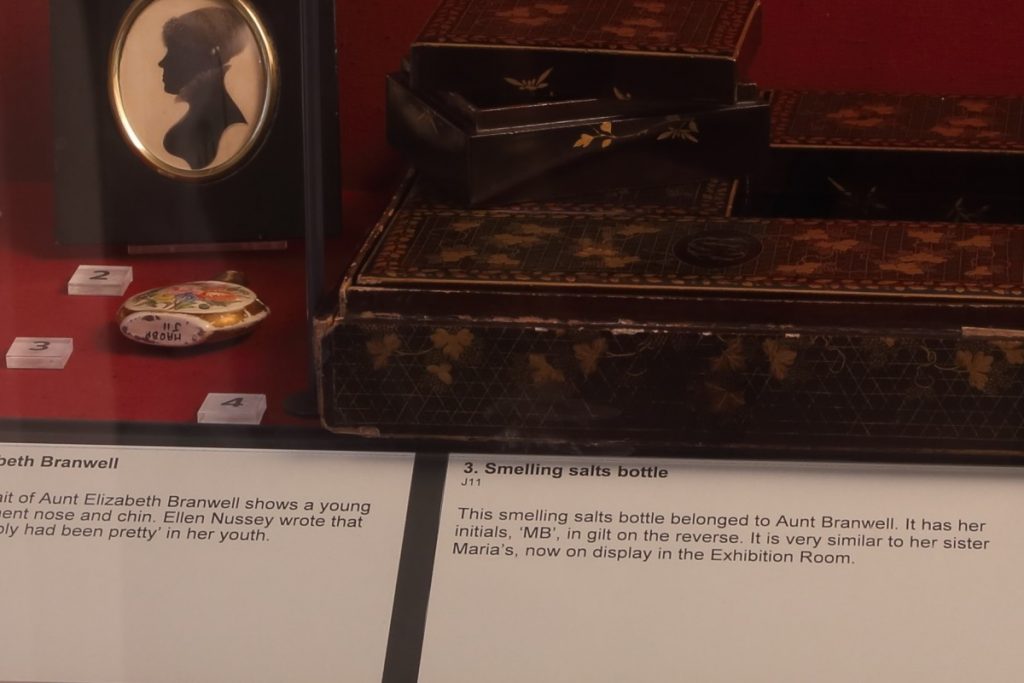

On previous Halloween weekends this blog has looked at the Gytrash that haunted Ponden Hall, and which had a cameo in Villette, the ghost of Anne Brontë supposedly seen on a staircase in New York, and even the theory that Anne was a vampire who inspired Bram Stoker’s Dracula. In this year’s post we’re going to look at a ghostly story that came from another resident of the Haworth Parsonage: Aunt Elizabeth Branwell.

Aunt Branwell, as she came to be known to the nieces she raised as a second mother, was born in Penzance, Cornwall and didn’t move to Yorkshire until 1821 when she was in her mid-forties (although she had spent over a year at the Brontë birthplace in Thornton earlier). Prior to that she had lived in Penzance and it was there that she heard a tale of tragedy that befell one of her neighbours, and which turned into a tale of horror worthy of any Halloween.

The story dates from 1803 and concerns a Mrs Baines, the wealthy widow of a Captain Baines, who lived at 25 Chapel Street. I will let the nineteenth century Cornish chronicler William Bottrell relate what happened next:

‘Mrs. Baines’s orchard, a pleasant spot, in which the lady took great delight, was stocked with the choicest apple, pear, plum, and other fruit trees then known. The town boys soon found out the fine flavour of Mrs. Baines’s fruit, which was to them all the sweeter for being stolen. When the apples were ripe and most tempting, the mistress and her serving-man watched the garden by turns – the man during the first part of the night, and madam would descend in her night-dress, every now and then, to see that all was right, in the small hours of morning. One night Mrs. Baines, suspecting that her man John was rather careless in keeping guard, sallied forth to see if he was attending to his duty; and, not finding him anywhere about the garden, she went to a tree of highly-prized apples and shook down a good quantity, intending to take them away, and thus prove to John that, through his remissness, the fruit was stolen. But her man John, armed with an old blunderbus, charged with peas and small shot, was at no great distance dozing under a hedge. The rustling of shaken branches, and noise of falling apples, awoke him, and, seeing somebody, as he thought, stealing apples from their favourite tree, he up with his gun and let fly at his mistress, exclaiming, at the same time, ” Now you thief, I’ve paid ‘e off’ for keeping me out of bed to watch ‘e! I know ‘e, I do, and will bring ‘e before his worship the mayor to-morrow!” “Lord help me, I’m killed!” cried the lady, as she fell on the ground.’

Mrs. Baines died of her wounds, and before long things took a sinister turn as locals reported seeing her ghost in the garden:

‘A short time after the old lady got shot, she died; and then she kept such ward and watch over her orchard that few were so bold as to enter, after day-down, into the haunted ground, where the ghost of Mrs. Baines was often seen under the tree where she was shot, or walking the grounds of her garden. Everybody knew the old lady by her upturned and powdered grey hair under a lace cap of antique pattern ; by the long lace ruffles hanging from her elbows ; her short silk mantle, gold-headed cane, and other trappings of old-fashioned pomp. There are many still living in Penzance who remember the time when they wouldn’t venture on any account to pass through Vounderveor-lane after night-fall, for fear of Mrs. Baines’ ghost. Sometimes she would flutter up from the garden or yard (just like an old hen flying before the wind), and perch herself on the wall: then, for an instant, one might get a glance of her spindle legs and high-heeled shoes before she vanished. Her walking in the garden might have been put up with, but she soon haunted all parts of the premises, and was often seen where least expected both by night and at noon. The ghost became so troublesome, at last, that no person could be found to occupy the house, where she was all night long tramping about from room to room, slamming the doors, rattling the furniture, and often making a fearful crash amongst glass and crockery.’

The new owners of the house called in a priest named Singleton to exorcise this property, giving the story of Mrs. Baines its truly bizarre end:

‘They sent for a parson, who was much famed in this neighbourhood as an exorcist that he might remove and lay the unresting spirit ; and he succeeded (by what means our informant knoweth not) in getting her away down to the sand-banks on the Western Green, which were then spread over many acres of land where the waves now roll. Here, this powerful parson, single-handed, bound her to spin from the banks ropes of sand for the term of a thousand years, unless she, before that time, spun a sufficiently long and strong one to reach from St. Michael’s Mount to St. Clement’s Isle. The encroaching sea having swept away the sandbanks, Mrs. Baines’ ghost is probably gone with them, as she hasn’t been heard of for some years, and, if she returns, the present occupiers of the old abode wouldn’t mind her.’

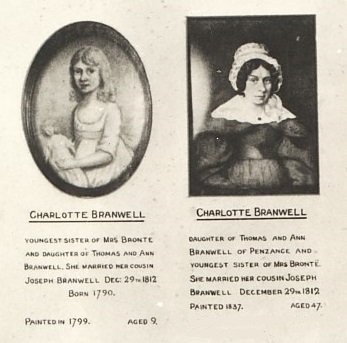

This is a fascinating story and one well known to Aunt Branwell as the widow Baines and her orchard were at 25 Chapel Street, whereas Elizabeth and her family lived at 62 Chapel Street, which was almost opposite the property. Certainly we can imagine the head of the household Thomas Branwell racing to his neighbour when he heard the night time gunshot, but what of the local children who liked to take the old woman’s sweet apples? Could they in earlier days have included Maria Branwell, who went on to become mother of the Brontës, or younger sister Charlotte Branwell, just 14 at the time of the tragedy, after whom Charlotte Brontë was named?

The locals avoided the Baines property in fear of seeing her hen like ghost, but Elizabeth and Maria Branwell would have often had no choice but to walk past it. In later years, Aunt Branwell related this story to her enthralled nieces and nephew. Parsonage servant Tabby Ayckroyd‘s storytelling is often credited for its influence on the Brontës, but equally important were the stories from Aunt Branwell: in the ghost of Mrs. Baines, for example, we can see a prototype of the ghostly nun of Villette.

If you walk past some old trees tonight and hear a rustling in the leaves, don’t look round – you don’t know who might be fluttering up to take her perch on the wall. Happy Halloween!