A couple of years ago I changed hosts for my Anne Brontë blog, and subsequently had to reload my older posts. It was a large but fun task, but some posts got lost in the change over. It’s come to my attention that my post on Hathersage was one of these, so apologies if you’ve seen it before but here it is again, slightly revamped, as we head back into the Peaks:

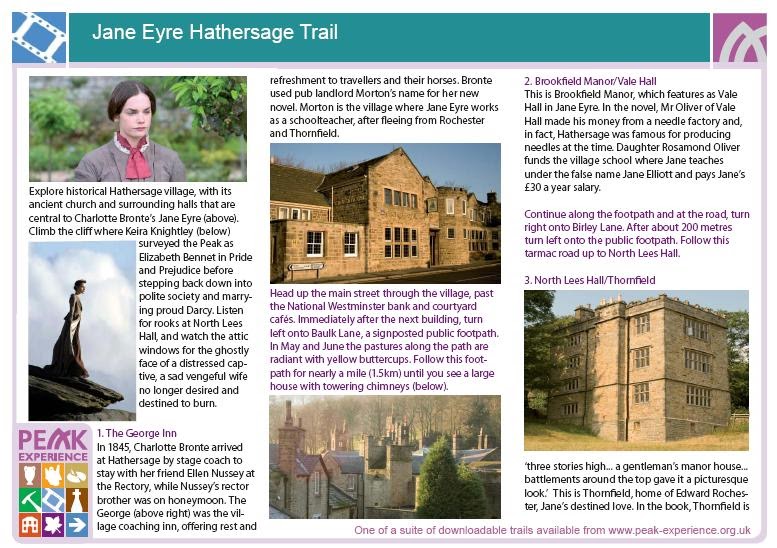

In recent posts we’ve taken a look at some of the locations, other than Haworth, that played a part in the light of Anne Brontë and her sisters, including last week’s recreation of the walk that she and Charlotte took through central London. In today’s blog we’re heading into the Peak district of Derbyshire, to the charming village of Hathersage.

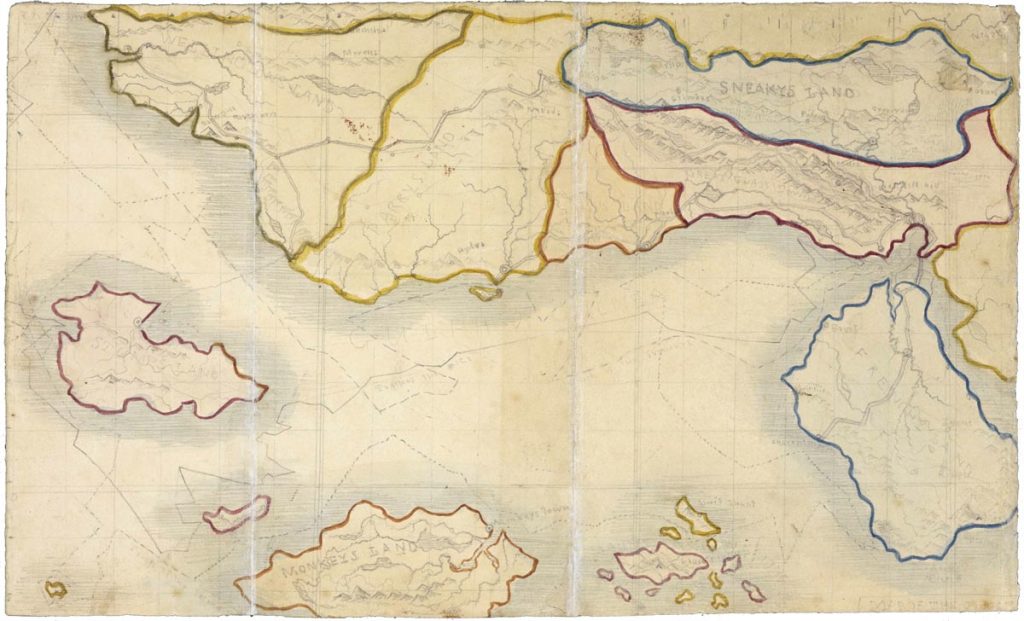

The Peak District is an area in the north of Derbyshire, to the south of Sheffield across the Yorkshire border. It is a wild, undulating and rugged place, full of valleys, hills, caverns and moors that were carved out during the ice age. It also has many villages and small towns that draw in tourists, such as Castleton, famed for its caverns full of the Blue John gemstone, Bakewell, home of the tart, and the ‘plague village’ of Eyam. Hathersage has one special attraction all of its own however: it features heavily in Charlotte Brontë’s ‘Jane Eyre‘.

Spoiler alert: after Jane discovers, on her wedding day, that Rochester is already married to a mad woman in the tower, she flees Thornfield Hall. She wanders penniless and heartbroken across a harsh landscape based upon the Peak District, before eventually reaching the village of Morton and begging to be given food and shelter. It is here that she meets St. John Rivers and the incredible ending to the novel takes shape.

Hathersage became a familiar haunt of Charlotte’s as she often visited it in company with her friend Ellen Nussey, who would also play a pivotal role in Anne Brontë’s life too of course. The reason for their visits was that Ellen’s brother Henry had been made vicar of St. Michael’s church in Hathersage. He served in that position from 1845 until 1847, during which time Charlotte discovered the places, and people, who would be pivotal to the novel.

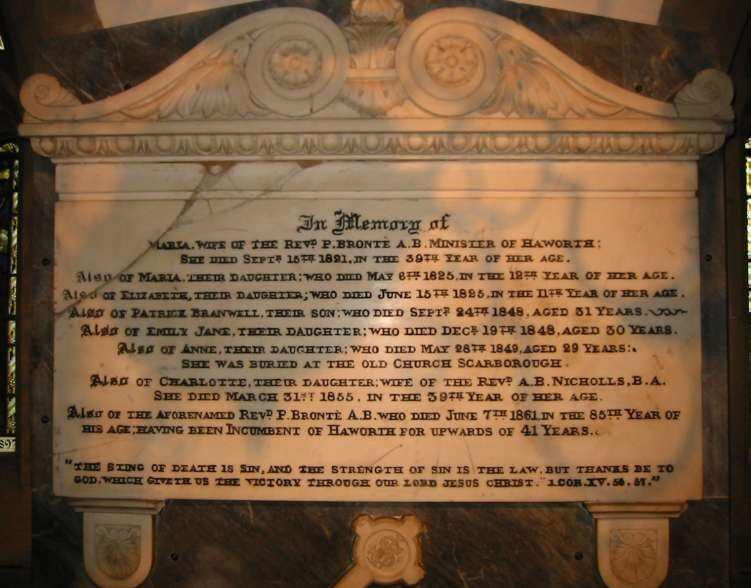

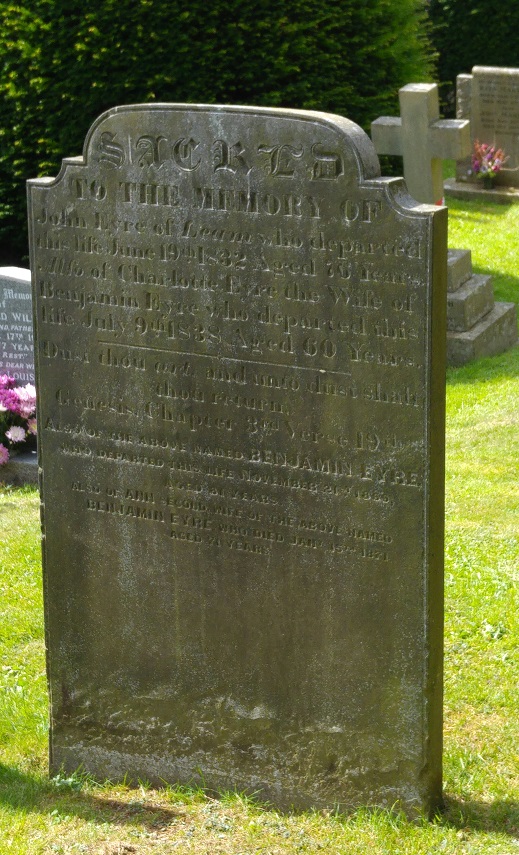

The leading family in the Hathersage area at that time was the Eyre family. In the church, Charlotte would have seen the Eyre memorial, and in the graveyard she would have found the Eyre graves, including one for a Jane Eyre herself.

The Eyre family resided at the grand North Lees Hall, just over a mile north of the village. Charlotte must have visited them here, or at least seen the hall, as it is unmistakably the inspiration for Rochester’s Thornfield Hall. Thus in real life, as opposed to the book, Jane Eyre and her family were in fact not the servants but the owners of Thornfield.

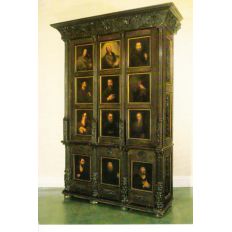

In the Hall, Charlotte also saw the incredible, if intimidating, apostle’s cabinet that she reproduced in Bertha’s chamber:

‘I must see the light of the unsnuffed candle wane on my employment; the shadows darken on the wrought, antique tapestry round me, and grow black under the hangings of the vast old bed, and quiver strangely over the doors of a great cabinet opposite — whose front, divided into twelve panels, bore, in grim design, the heads of the twelve apostles, each enclosed in its separate panel as in a frame; while above them at the top rose an ebony crucifix and a dying Christ.’

This very cabinet is now in the Brontë Parsonage Museum, just as Charlotte described it, presented to them by North Lees Hall.

Also of interest to Brontë lovers in Hathersage is the George Hotel, as it too features as the George Inn in Jane Eyre, the coaching inn employed by Jane and the stop at which Charlotte Brontë would have alighted on her visits to the village.

Hathersage’s church has become famous for its Eyre and Brontë connections, but it also has another remarkable claim to fame. At the foot of its churchyard is a very long grave, which is always beautifully kept. This, so legend states, is the final resting place of Little John, the faithful lieutenant of Robin Hood. Robin Hood is closely connected with the area, and is often claimed to be from Loxley, to the north of Hathersage near the city of Sheffield.

It is said that in 1780, a man named James Shuttleworth dug up a thigh bone there, and measured it at over twenty-eight inches. This would have made Little John more than eight feet tall. It’s also said that John’s bow and chainmail once hung in the church, although no trace of them now remains.

Robin Hood has another connection to Charlotte and Anne Brontë. On the outskirts of Mirfield stands Kirklees Hall. Legend states that it is here that Robin Hood died, having been treacherously poisoned. In his dying moment he shot an arrow out of his window and was buried where he fell, somewhere in the woodland around the Hall. This legend would have been very well known to Charlotte and Anne Brontë, as Kirklees Hall is close to the Roe Head School at which they studied.

Hathersage was certainly a huge influence on Charlotte Brontë, and we can surmise that she must have enjoyed her time there. It may also have been a little strained at times, however. In 1839, Henry Nussey had proposed to Charlotte, and been summarily rejected. It is thought that he could have been a forebear of the pious yet overbearing St. John Rivers of Jane Eyre. By the time he became a vicar he had married Emily Prescott, but Henry’s life was to have a tragic ending.

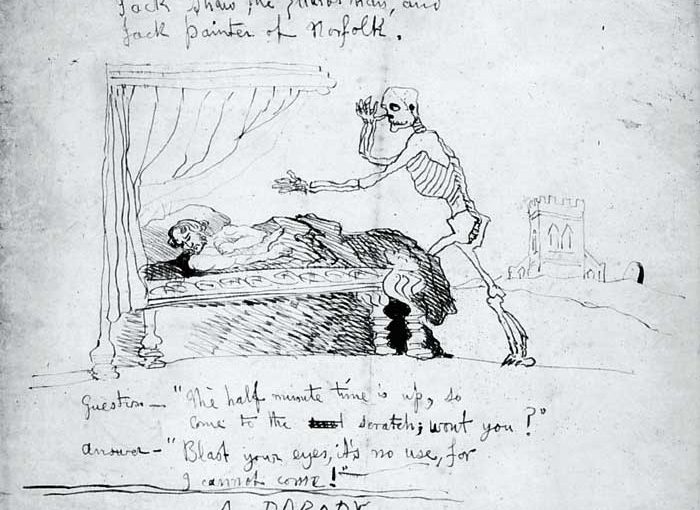

After leaving Hathersage, he left the church altogether. Throughout the rest of his life he suffered from mental illness, and was interred in a succession of mental asylums. It was in such a place, Arden House, that he eventually took his own life in January, 1860. His condition had earlier been described as: ‘violent and dangerous to himself and others.’

Setting such a dark moment aside, there is plenty for Brontë fans to see and do in Hathersage, and in its stunning Peak District surroundings.