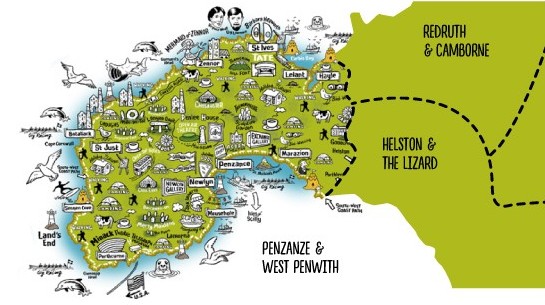

199 years ago today, a very special girl was born in the parish of Thornton near Bradford. She was the fifth child of the parish priest and his Cornish wife, and as they looked down on their new baby they could little have guessed the impact she would have on the world of literature. She was no ordinary baby, she was Emily Jane Brontë.

When you think of the impact that she has made on readers it’s astonishing to think that Emily Brontë wrote just one novel, the supremely powerful Wuthering Heights before being struck down by tuberculosis aged just thirty. Less than two years after Emily’s own birth she gained a younger sister in the form of Anne Brontë and just a few months later the family would move to a new parish, the nearby village of Haworth.

Emily lost her mother Maria when she was just three years old. She and Anne being the youngest in the family, they clung to each other for comfort and support throughout their childhood and into their adult lives. Both girls were extremely shy, often hugging each other for comfort when in the company of strangers and hiding away together, and they shared many of the same interests: from walking the moors, to playing the piano, from looking after their ever expanding collection of pets to reading the exciting adventure stories of Walter Scott.

As Emily and Anne grew up together their love for each other strengthened, and became almost twin like. Family friend Ellen Nussey saw this first hand, and as well as noting how they walked with their arms entwined with each others whenever possible, she said: “She and Anne were like twins – inseparable companions, and in the very closest sympathy, which never had any interruption.”

It was Ellen who also gave us a description of the teenage Emily: “Emily had by this time acquired a lithesome, graceful figure. She was the tallest person in the house, except her father. Her hair, which was naturally as beautiful as Charlotte’s, was in the same unbecoming tight curl and frizz, and there was the same want of complexion. She had very beautiful eyes, kind, kindling, liquid eyes; but she did not often look at you: she was too reserved. She talked very little.”

Emily was by far the tallest of the Brontë sisters, and was generally of strong and robust health as well, and yet she couldn’t master her shyness. When she went to Roe Head school, where her sister Charlotte was teaching, she became so homesick that she had to be sent home for fear of her life itself, as Charlotte relates: “Every morning when she woke the vision of home and the moors rushed on her, and darkened and saddened the day that lay before her. Nobody knew what ailed her but me – I knew only too well. In this struggle her health was quickly broken: her white face, attenuated form, and failing strength threatened rapid decline. I felt in my heart she would die, if she did not go home.”

It was Anne who took Emily’s place, although also suffering from shyness throughout her life she mastered it in a way that her elder sister never could. As children Emily and Anne wrote a vast array of poetry and prose about their imagined kingdom of Gondal, and soon the lines between Gondal reality and Haworth reality became blurred for Emily. She retreated further and further into her world of make belief, and was never happier than when alone on the moors – occasions that took on a spiritual and mystical aspect for her.

It was Emily’s poetry that was responsible for the wonderful work of the Brontë sisters that we know and love today. It was well known to her sisters that Emily still wrote Gondal poetry, but she also had a secret book in which she wrote non-Gondal poetry. When Charlotte ‘accidentally’ discovered this book the course of literary history was changed forever:

“One day, in the autumn of 1845, I accidentally lighted on a manuscript volume of verse in my sister Emily’s handwriting. Of course, I was not surprised, knowing that she could and did write verse: I looked it over, and something more than surprise seized me, – a deep conviction that these were not common effusions, nor at all like the poetry women generally write. I thought them condensed and terse, vigorous and genuine. To my ear, they also had a peculiar music – wild, melancholy, and elevating.”

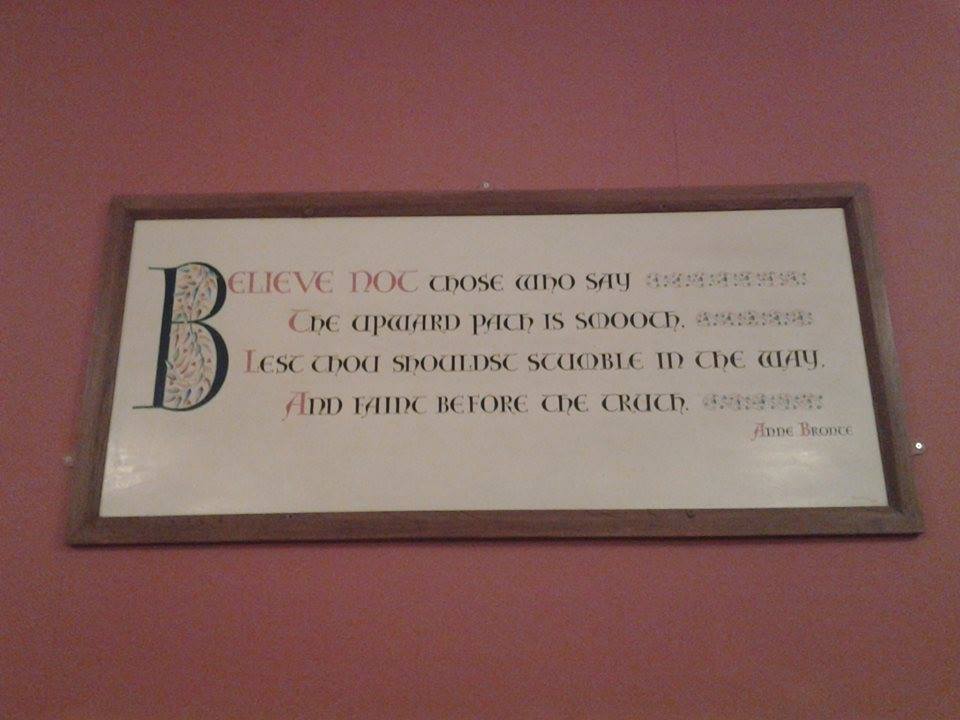

A terrible argument ensued as Charlotte tried to persuade Emily to have her poetry published, but her reserve was finally defeated when Anne and Charlotte agreed to contribute their poems as well. The result was ‘Poems by Currer, Ellis, and Acton Bell’. It sold only two copies, but the sisters had now got the writing bug and decided that for their next venture they would each attempt a prose volume that they could have published jointly. Charlotte’s contribution, ‘The Professor’, was rejected but Emily’s ‘Wuthering Heights’ and Anne’s ‘Agnes Grey’ were published together by Thomas Cautley Newby & Co in 1847.

Emily was disdainful of literary success, and of the criticism that her novel received. It was as if she had lain pearls before swine, and she would not make that mistake again. The publication of ‘Wuthering Heights’ marked the end of Emily’s writing life completely, with just one poem written subsequent to it; her prodigious output of poetry is amongst the best written in the English language, and often has a visionary quality that reveals to us the inner world Emily was living in. Outwardly calm and quiet, by the candlelight of nigh she would be visited by incredible and elating visions that would power and inform her writing.

I personally have a lot to be thankful to Emily for. ‘Wuthering Heights’ was the first novel on my reading list at University, and within a few sentences I was hooked. My love of the Brontës was formed, and it has brought untold joy into my life ever since. That very weekend I made my first journey to the Brontë Parsonage Museum at Haworth and bought a portrait claimed to be of Emily Brontë (although I now feel that it is actually of Anne); it hung on my wall as a student for three years.

Next year will be a very special year indeed as we mark the 200th anniversary of Emily’s birth, and I’m proud that my biography of Emily will be released to mark the occasion. For now, we can all celebrate by reading some of Emily’s poetry, her astonishing novel, or watching a film version of ‘Wuthering Heights’ as we say ‘Happy 199th Birthday, Emily Brontë’!