Thank you to all who watched me at the online Felixstowe Book Festival on Friday – I really enjoyed it, and if you missed it you can catch some of the action via this link: https://www.facebook.com/watch/live/?v=584953558891931&ref=watch_permalink

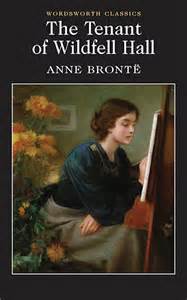

I was asked some excellent questions, and one woman wanted to know how much Branwell Brontë had influenced Arthur Huntingdon in Anne’s brilliant novel The Tenant Of Wildfell Hall, so that’s what we’re going to look at today.

Arthur is possibly the most villainous of all Brontë characters – Heathcliff may run him close, but at least we can see from his back story where his seething jealousy and anger comes from. Arthur is wealthy and handsome, with all the advantages privilege can bring, and yet he cares for absolutely nothing but his own pleasure.

Huntingdon is a narcissist and a hedonist, but everything he does is taken to extremes. He drinks heavily and takes drugs, he cheats on his wife and abuses her physically and mentally, and does his best to corrupt his young son so that he will grow up to be as venal as his father. Living life so recklessly produces the inevitable ending, and Arthur dies at a young age, presumably from liver failure caused by his excessive alcohol consumption.

Anne Brontë, as we know of course, is a brilliant novelist, and so skilfully does she depict Arthur’s behaviour that people often think she must have drawn it from real life – and then their attention usually turns to her brother Branwell.

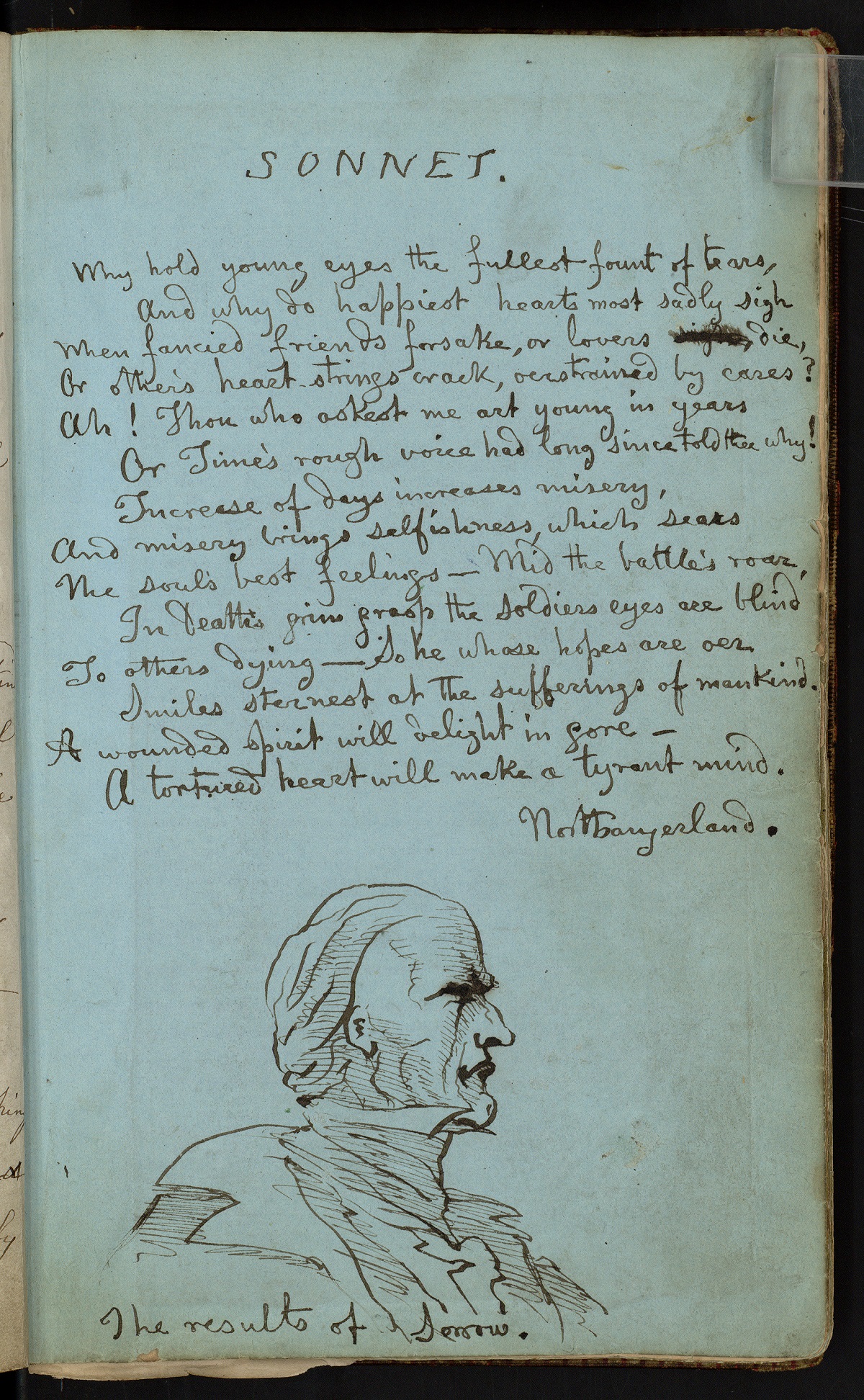

Charlotte Brontë, too, may have thought that Huntingdon is a portrait, at least in part, of their brother – after all, he too was addicted to alcohol and opiates, and his behaviour was increasingly erratic in his final years. In her autobiographical notice of Anne and Emily, Charlotte wrote:

‘The Tenant Of Wildfell Hall by Acton Bell, had likewise an unfavourable reception. At this I cannot wonder. The choice of subject was an entire mistake. Nothing less congruous with the writer’s nature could be conceived. The motives which dictated this were pure, but, I think, slightly morbid. She had in the course of her life, been called on to contemplate, near at hand and for a long time, the terrible effects of talents misused and faculties abused; hers was naturally a sensitive, reserved and dejected nature; what she saw sank very deeply into her mind; it did her harm. She brooded over it till she believed it to be a duty to reproduce every detail as a warning to others.’

Whose talents misused and facilities abused had Anne been called on to contemplate near at hand and for a long time? In the aftermath of Branwell’s death, Charlotte wrote to W. S. Williams:

‘When I looked on the noble face and forehead of my dead brother… and asked myself what had made him go ever wrong, tend ever downwards, when he had so many gifts to induce to, and aid in an upward course – I seemed to receive an oppressive revelation of the feebleness of humanity.’

Charlotte saw Branwell in Huntingdon in The Tenant Of Wildfell Hall, and it may be this that turned her against what is, on any objective view, a brilliant work of literature, but is Branwell Brontë really the prototype of Arthur Huntingdon? I don’t think so.

Certainly Anne would have seen Branwell’s drunken behaviour, but Branwell was far from the unredeemed villain that we see in Huntingdon. He could be kind, thoughtful and loving, especially in his younger days when the four surviving Brontë siblings were very close. We also know that on occasion Branwell managed to quit his drug dependency by going cold turkey, which points to his influence on another character altogether within The Tenant Of Wildfell Hall: Lord Lowborough.

Lowborough is first seen as one of Huntingdon’s crowd of pleasure seekers, but he eventually turns his back on their antics and weans himself off opiates. Perhaps then this is closer to Anne’s view of Branwell: a man who has been troubled, who has burdens to bear, but who is capable of redemption. I think perhaps the best, and most touching, description of Branwell’s character comes in Francis Grundy’s Pictures Of The Past in which he devotes a chapter to a man who’d been a close friend: ‘Branwell Brontë was no domestic demon – he was just a man moving in a mist, who lost his way.’

Branwell was no domestic demon, although he could certainly on occasion cause domestic turmoil, but Arthur Huntingdon was, so if Branwell wasn’t the inspiration for Huntingdon, who was? One possibility is Edmund Robinson, Anne’s, and later Branwell’s, employer at Thorp Green Hall. Edmund was a member of the gentry who could live comfortably and extravagantly, just like Arthur. He was a choleric man who liked hunting and drinking. Although ordained as a priest in the Church of England (common then among younger sons of the aristocracy who wouldn’t inherit a title), he never held a curacy and only officiated at family baptisms and on one other occasion: the baptism of a young girl from Thorp Green village. We can speculate why he took such an interest in this infant – could he, like Arthur, have been serially unfaithful to his wife, and could this be one reason why Lydia Robinson, in her turn, took an interest in Branwell Brontë – a man who respected her and showed her affection? He died aged 46, possibly as a result of his intemperate lifestyle.

Another man who is sometimes named as a Huntingdon suspect is George Gordon, better known as Lord, Byron. He certainly behaved abominably towards his wife Annabella, having numerous affairs including with his own half-sister Augusta Leigh. In December 1815 they had a daughter Ada, who is now famed as the mathematical and computing pioneer Ada Lovelace, but just a month later Annabella took her baby and left Byron for good.

There is one possible inspiration for Arthur, certainly for Helen, closer to home for Anne. Her aunt Jane, from the Branwell family of Penzance, married the Methodist minister Reverend John Kingston, but six years into their marriage a scandal engulfed the family. John had been discovered having affairs with other men and with having committed theft, and he was thrown out of the Methodist church. With his job gone and name tarnished, John took Jane and their family to start a new life in Baltimore, America.

It seems that their marriage must have disintegrated further in Maryland, for just a year later Jane left her husband and sailed back to England with her baby daughter Eliza, tragically having to leave her older children with their father. With the help of her sister Elizabeth she set up a laundry business back in Penzance, and lived as a single parent. It seems clear to me that Elizabeth, Aunt Branwell, must have told her nieces at least some of this story, and that Aunt Jane became a prototype for Helen.

In summary then, I don’t think Branwell was Arthur – for all his frailties he was much loved by Anne, who had found him a job alongside her at Thorp Green Hall, but I do think Arthur could have been influenced by Edmund Robinson, John Kingston and even Lord Byron. Like all great writers, Anne took a variety of sources and life experiences and created something powerful and original. Whoever the inspirations are, we can all agree that The Tenant Of Wildfell Hall is a brilliant book that is as relevant today as it’s ever been. Stay happy and healthy, and I will see you again next Sunday for another new Brontë blog post.