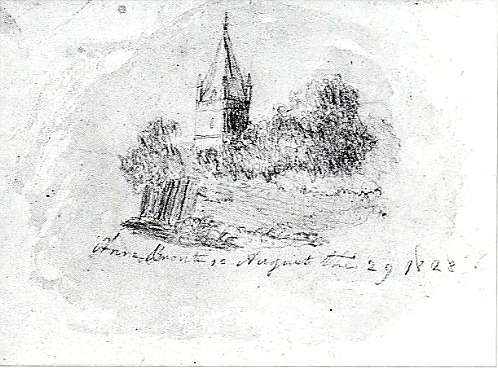

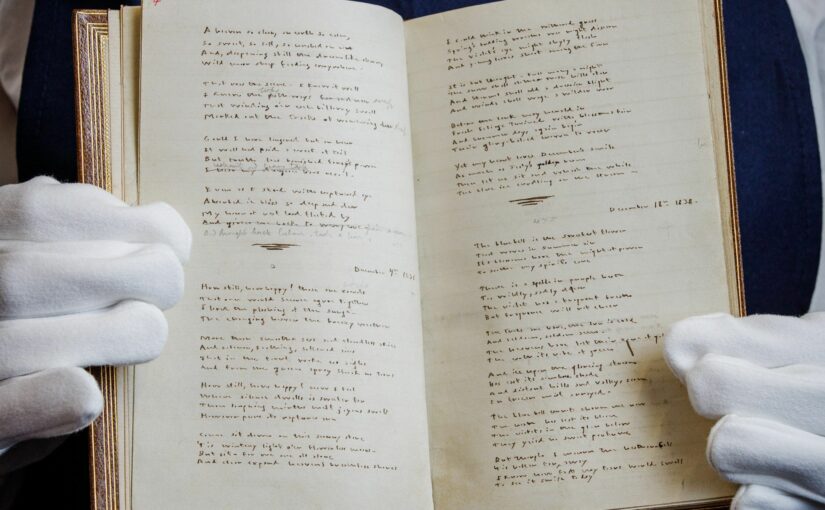

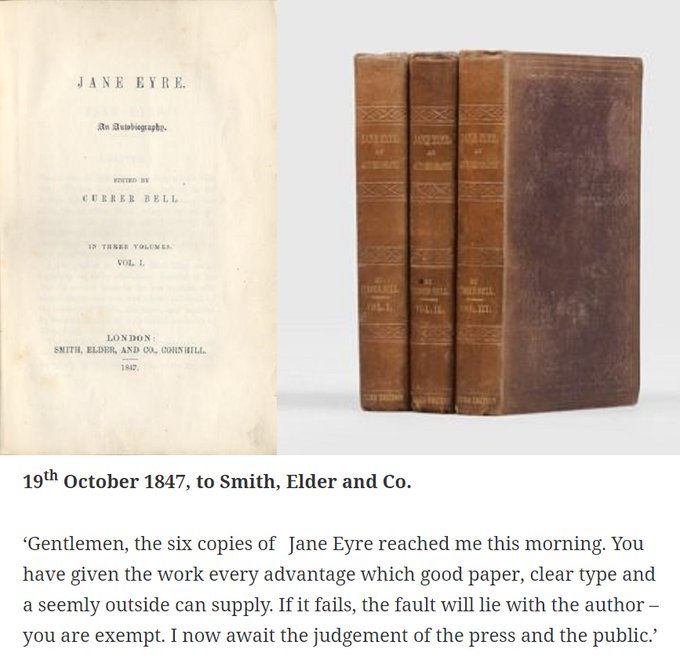

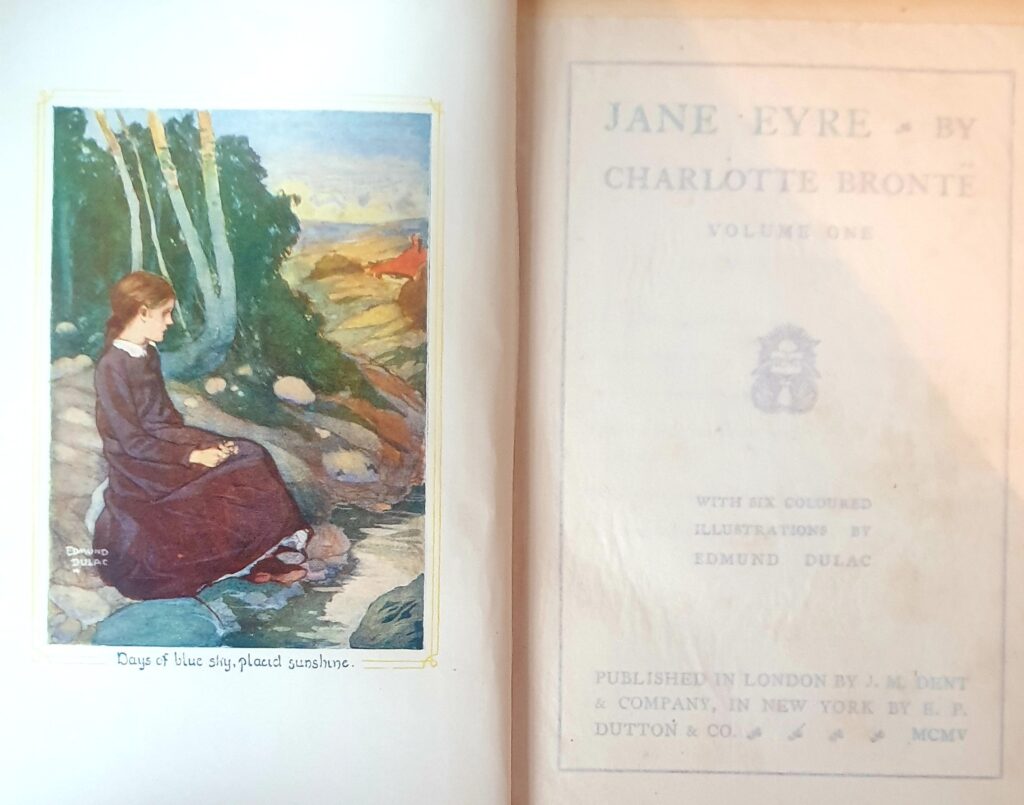

On this week in 1847 a new author made their writing debut. Published by Smith, Jones & Co. the book Jane Eyre: An Autobiography marked the first appearance before the public of the mysterious Currer Bell. Nobody knew who Bell was or where he had come from, including his own publisher, but the reading public, if not necessarily all the critics, soon agreed that he had written a very excellent book indeed. Two centuries later the reading public still agrees with that, although we now know of course that Mr Currer Bell was in fact Miss Charlotte Brontë.

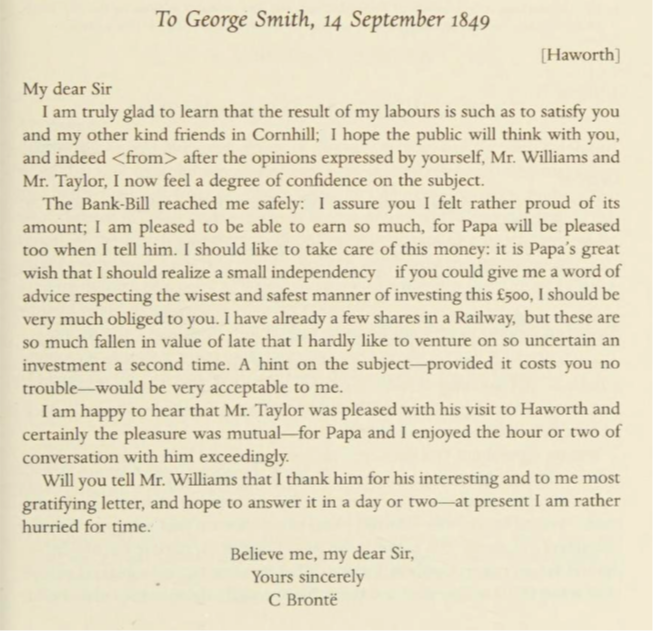

The precise date of the publication is unknown, but it is generally thought to be on the 16th October 1848 as Elizabeth Gaskell wrote that the date of publication of Jane Eyre was ‘no later than 16th October’. What we do know for sure is that three days later on the 19th October Charlotte received her six free author copies – and what a proud moment that must have been to her. Here is Charlotte’s letter thanking her publisher:

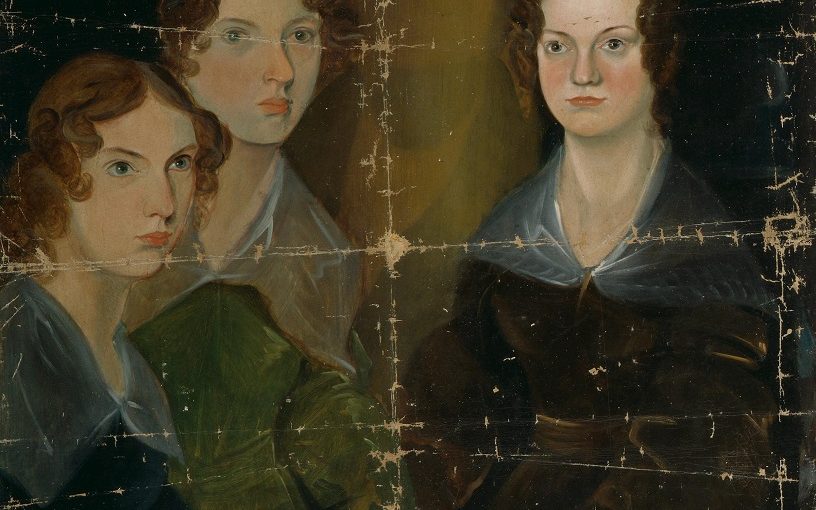

This day was a triumph for great storytelling, a triumph for literature, but it was also a triumph over adversity. Jane Eyre was written in a time of mental and physical darkness for Charlotte. Her first written novel The Professor had been rejected by every single publisher it was sent to, whilst at the same time her sisters Emily and Anne had their novels Wuthering Heights and Agnes Grey accepted. This must have sown great doubts in Charlotte’s mind: she was the older sister, it was she who had always led their writing endeavours, but could it be that whilst her sisters were talented writers she was not?

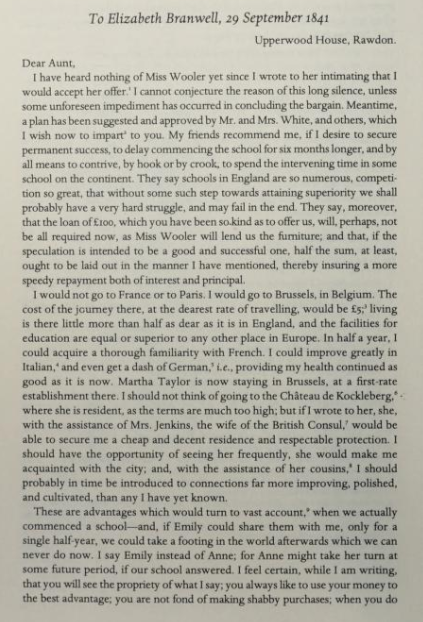

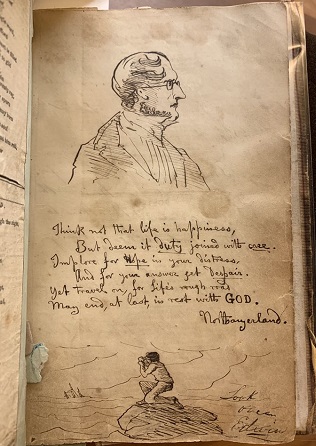

At the same time, Charlotte had accompanied her father to Manchester where her father Patrick had received eye surgery to restore his sight. Elizabeth Gaskell recalled the scene as recounted to her by Charlotte:

“Among the dispiriting circumstances connected with her anxious visit to Manchester, Charlotte told me that her tale came back upon her hands, curtly rejected by some publisher, on the very day when her father was to submit to his operation. But she had the heart of Robert Bruce within her, and failure upon failure daunted her no more than him. Not only did The Professor return again to try his chance among the London publishers, but she began, in this time of care and depressing inquietude – in those grey, weary, uniform streets, where all faces, save that of her kind doctor, were strange and untouched with sunlight to her, – there and then, did the genius begin Jane Eyre.”

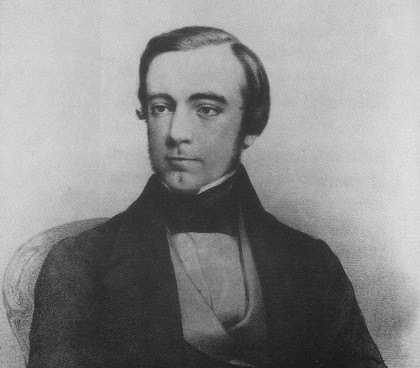

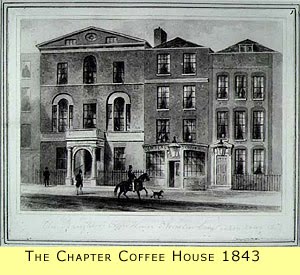

Charlotte’s publisher George Smith recounted the effect that receipt of Charlotte’s manuscript had upon him and his assistant W. S. Williams. Smith began reading it in his stately London mansion on Sunday morning, cancelled his lunch, cancelled a meeting and read it all in one day. It was published just as quickly, and in fact it reached the shops and circulating libraries before Emily and Anne Brontë’s work had yet been published.

A little over a week after its publication it was clear that Jane Eyre and Currer Bell were an overnight success. Even Charlotte’s hero William Makepeace Thackeray had read the novel and approved of it, as we see from a letter Charlotte, still hiding behind her Currer Bell nom de plume, sent to William Smith Williams:

Typically modest, and typically full of self-doubt, Charlotte ended her letter hoping that the novel would be a success, and ascribing any success that did accrue not to herself but to the efforts her publisher had made!

Elizabeth Gaskell was right, as she was on so many things connected to her great friend: Charlotte Brontë had the heart of Robert the Bruce, she triumphed because she refused to give in. Let that be an example to us all, and I hope to see you next week for another new Brontë blog post.