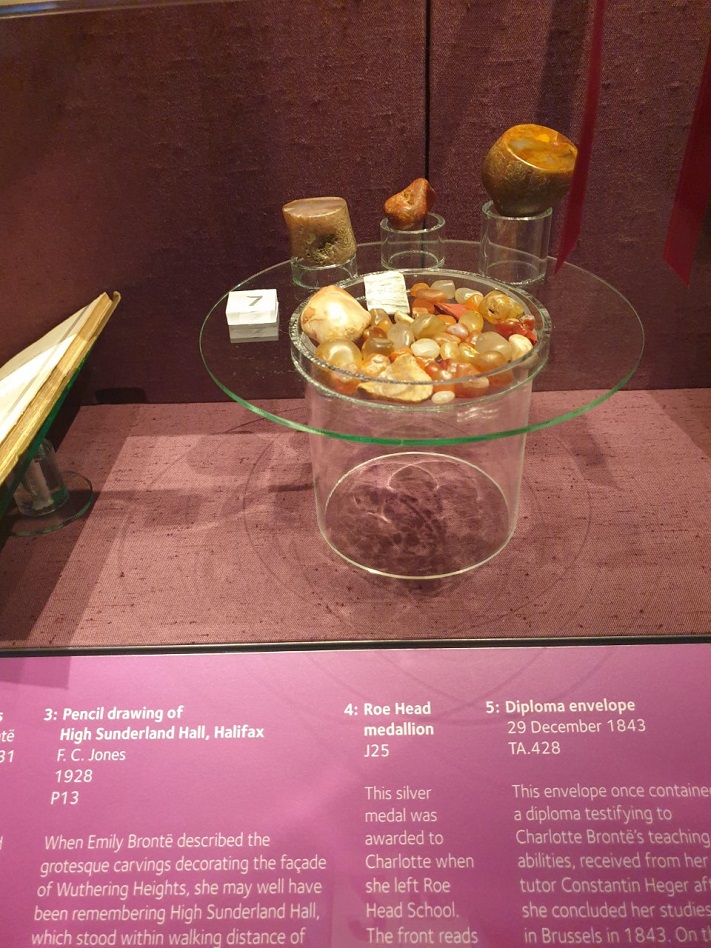

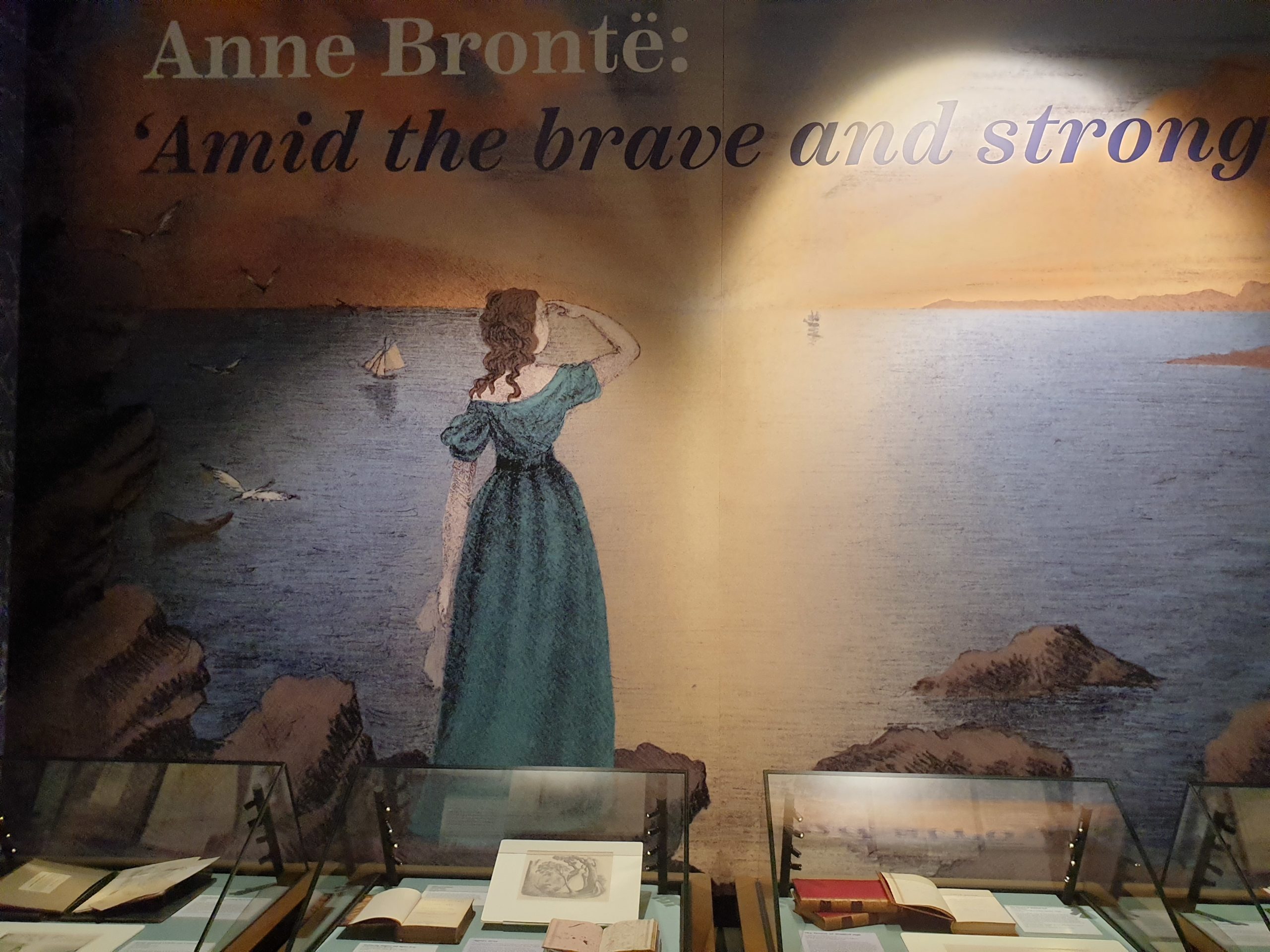

Thank you so much for all the kind words about my recent posts taking you on a virtual tour of the new Anne Brontë exhibition at the Brontë Parsonage Museum in Haworth, it was a pleasure to share it with you. With new lockdown restrictions appearing across the country we once again turn to books for solace; after all, they never let us down. The clocks have gone backwards, some might say to the fourteenth century, and the dark nights are here. Late October is certainly making her presence felt, so in today’s post let’s take a look at October in the Brontë novels.

Jane Eyre

‘A new chapter in a novel is something like a new scene in a play; and when I draw up the curtain this time, reader, you must fancy you see a room in the George Inn at Millcote, with such large figured papering on the walls as inn rooms have; such a carpet, such furniture, such ornaments on the mantelpiece, such prints, including a portrait of George the Third, and another of the Prince of Wales, and a representation of the death of Wolfe. All this is visible to you by the light of an oil lamp hanging from the ceiling, and by that of an excellent fire, near which I sit in my cloak and bonnet; my muff and umbrella lie on the table, and I am warming away the numbness and chill contracted by sixteen hours’ exposure to the rawness of an October day: I left Lowton at four o’clock a.m., and the Millcote town clock is now just striking eight. Reader, though I look comfortably accommodated, I am not very tranquil in my mind.’

October brings new opportunities for Jane after leaving her position as a teacher at Lowood school, and we see her now preparing to enter her life as a governess at Thornfield Hall. The George Inn at Millcote is clearly modelled on the George Inn (now the George Hotel) at Hathersage, the Derbyshire village visited by Charlotte Brontë and Ellen Nussey. You can still visit the George Inn today and see the portraits of George III and the Prince of Wales on its walls.

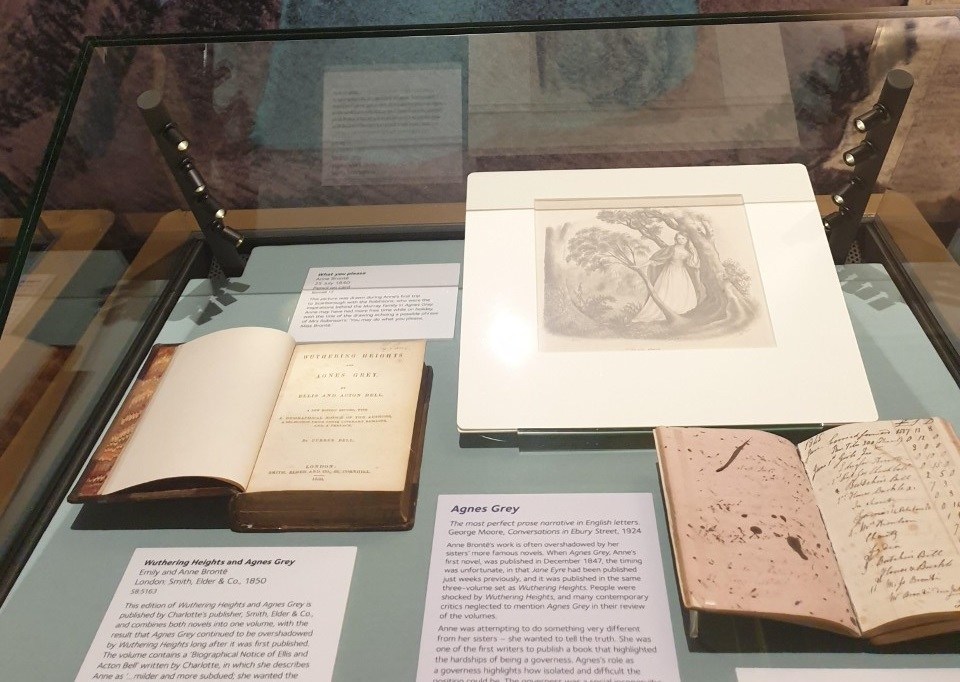

Wuthering Heights

‘But the hour came, at last, that ended Mr. Earnshaw’s troubles on earth. He died quietly in his chair one October evening, seated by the fire-side. A high wind blustered round the house, and roared in the chimney: it sounded wild and stormy, yet it was not cold, and we were all together—I, a little removed from the hearth, busy at my knitting, and Joseph reading his Bible near the table (for the servants generally sat in the house then, after their work was done). Miss Cathy had been sick, and that made her still; she leant against her father’s knee, and Heathcliff was lying on the floor with his head in her lap. I remember the master, before he fell into a doze, stroking her bonny hair—it pleased him rarely to see her gentle—and saying, “Why canst thou not always be a good lass, Cathy?” And she turned her face up to his, and laughed, and answered, “Why cannot you always be a good man, father?” But as soon as she saw him vexed again, she kissed his hand, and said she would sing him to sleep. She began singing very low, till his fingers dropped from hers, and his head sank on his breast. Then I told her to hush, and not stir, for fear she should wake him. We all kept as mute as mice a full half-hour, and should have done so longer, only Joseph, having finished his chapter, got up and said that he must rouse the master for prayers and bed. He stepped forward, and called him by name, and touched his shoulder; but he would not move: so he took the candle and looked at him. I thought there was something wrong as he set down the light; and seizing the children each by an arm, whispered them to “frame upstairs, and make little din—they might pray alone that evening—he had summut to do.”

“I shall bid father good-night first,” said Catherine, putting her arms round his neck, before we could hinder her. The poor thing discovered her loss directly—she screamed out—“Oh, he’s dead, Heathcliff! he’s dead!” And they both set up a heart-breaking cry.’

October is a time for change in the Earnshaw household too, but this time we are bathed in tragedy. This is the end of childhood happiness and innocence for Catherine and Heathcliff, their roles will now change forever, setting in sequence the often violent and tragic action to come.

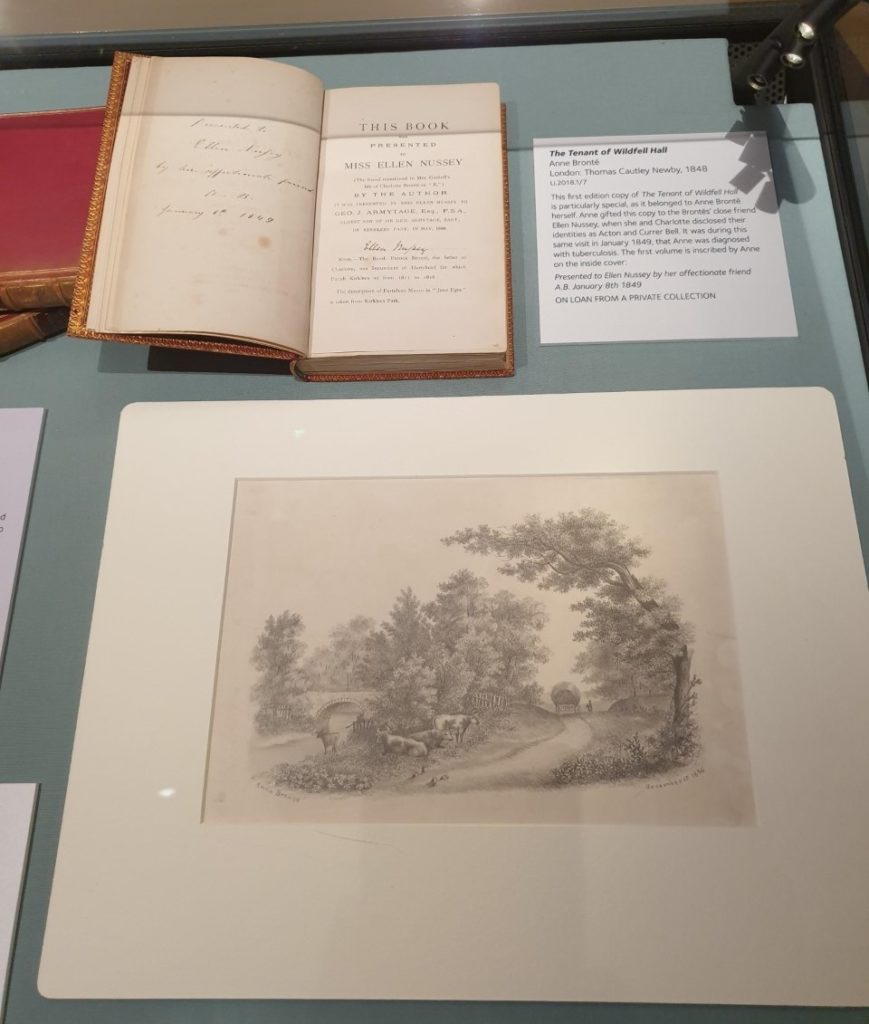

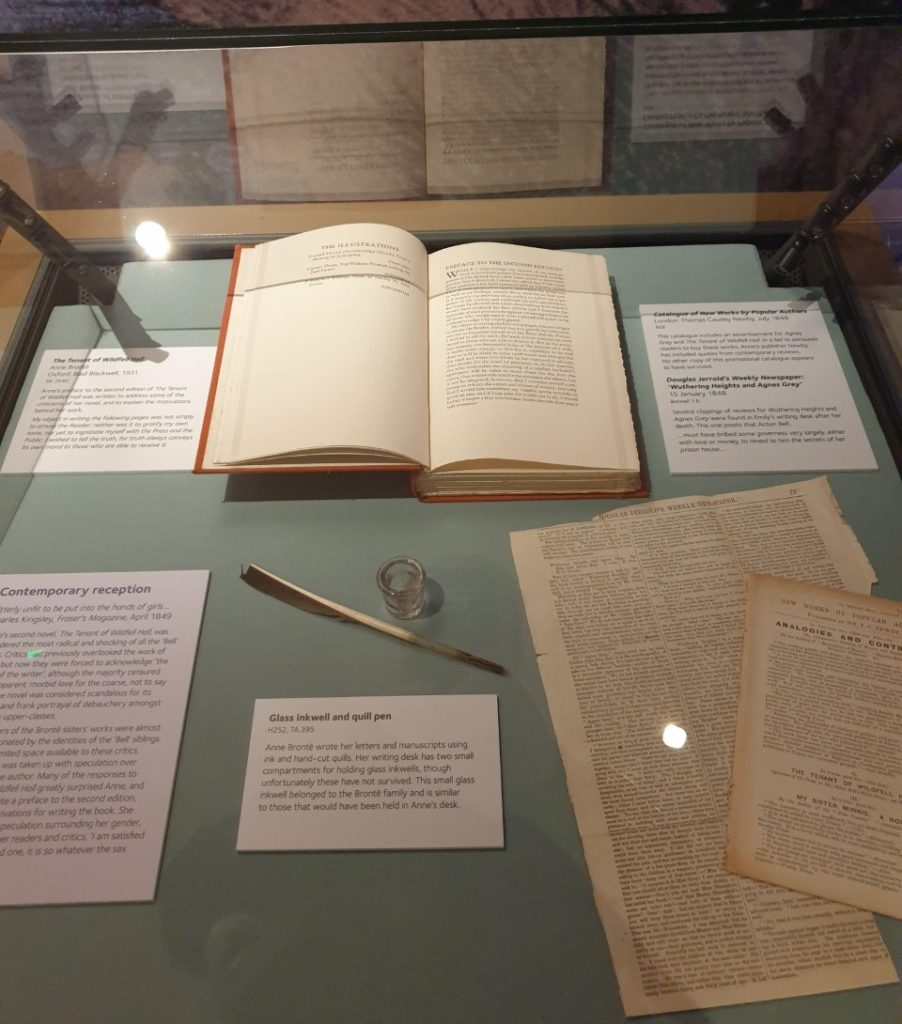

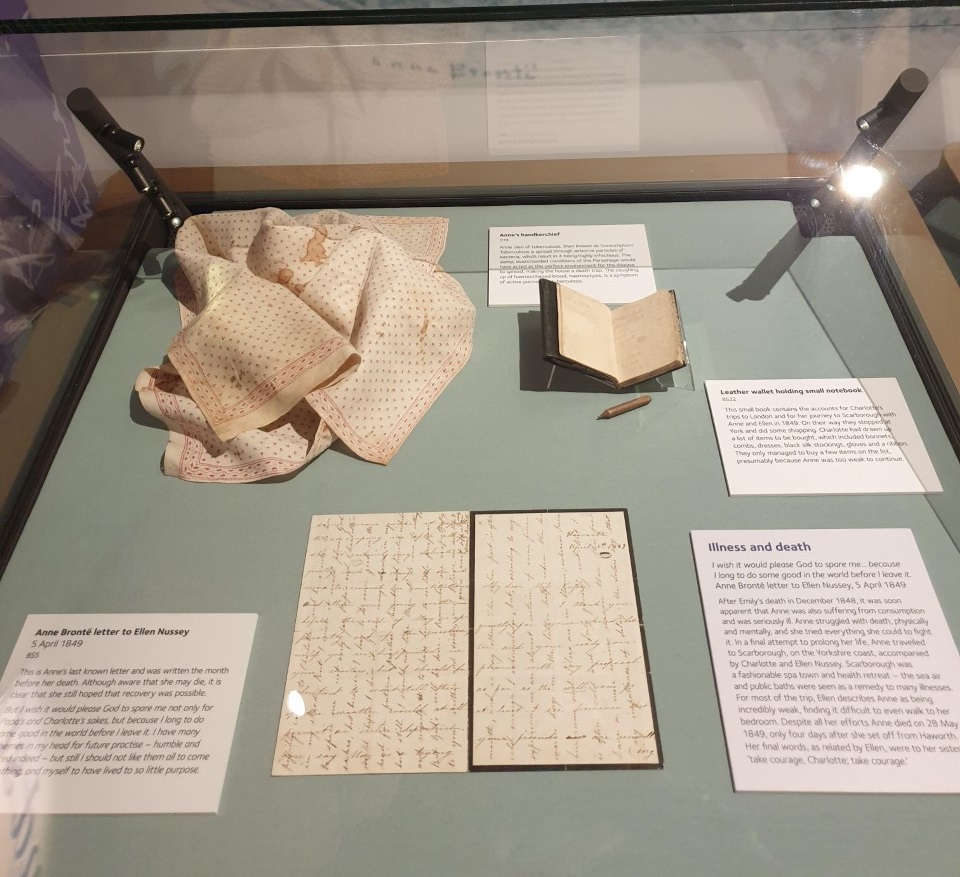

The Tenant Of Wildfell Hall

‘October 1st.—All is settled now. My father has given his consent, and the time is fixed for Christmas, by a sort of compromise between the respective advocates for hurry and delay. Milicent Hargrave is to be one bridesmaid and Annabella Wilmot the other—not that I am particularly fond of the latter, but she is an intimate of the family, and I have not another friend.’

‘October 9th.—It was on the night of the 4th, a little after tea, that Annabella had been singing and playing, with Arthur as usual at her side: she had ended her song, but still she sat at the instrument; and he stood leaning on the back of her chair, conversing in scarcely audible tones, with his face in very close proximity with hers. I looked at Lord Lowborough. He was at the other end of the room, talking with Messrs. Hargrave and Grimsby; but I saw him dart towards his lady and his host a quick, impatient glance, expressive of intense disquietude, at which Grimsby smiled. Determined to interrupt the tête-à-tête, I rose, and, selecting a piece of music from the music stand, stepped up to the piano, intending to ask the lady to play it; but I stood transfixed and speechless on seeing her seated there, listening, with what seemed an exultant smile on her flushed face to his soft murmurings, with her hand quietly surrendered to his clasp. The blood rushed first to my heart, and then to my head; for there was more than this: almost at the moment of my approach, he cast a hurried glance over his shoulder towards the other occupants of the room, and then ardently pressed the unresisting hand to his lips. On raising his eyes, he beheld me, and dropped them again, confounded and dismayed. She saw me too, and confronted me with a look of hard defiance. I laid the music on the piano, and retired. I felt ill; but I did not leave the room: happily, it was getting late, and could not be long before the company dispersed.’

‘October 24th.—Thank heaven, I am free and safe at last. Early we rose, swiftly and quietly dressed, slowly and stealthily descended to the hall, where Benson stood ready with a light, to open the door and fasten it after us. We were obliged to let one man into our secret on account of the boxes, &c. All the servants were but too well acquainted with their master’s conduct, and either Benson or John would have been willing to serve me; but as the former was more staid and elderly, and a crony of Rachel’s besides, I of course directed her to make choice of him as her assistant and confidant on the occasion, as far as necessity demanded, I only hope he may not be brought into trouble thereby, and only wish I could reward him for the perilous service he was so ready to undertake. I slipped two guineas into his hand, by way of remembrance, as he stood in the doorway, holding the candle to light our departure, with a tear in his honest grey eye, and a host of good wishes depicted on his solemn countenance. Alas! I could offer no more: I had barely sufficient remaining for the probable expenses of the journey.’

No Brontë book mentions October more than Anne Brontë’s The Tenant Of Wildfell Hall. This is perhaps understandable given that the middle section of the book takes the form of a diary written by Helen, but by following the October entries, just some of which are given above, we see the progression of Helen’s marriage and life. At first we have hope, followed by despair as she sees her husband Arthur’s behaviour and character, Finally, however, there is hope again as Helen finally escapes for a new life at Wildfell Hall. October can often seem a dark and challenging month, never more so by now, but as we see in Anne’s great novel it can end with hope and light – even if that light is caused by candles flickering inside pumpkins.

Wrap up warm, grab a nice drink and a great book, and I hope to see you next week, in November, for what I hope will be a very special post. Thank you, as always, for your company.

Normal service will be resumed in next week’s blog, so until then stay healthy and happy and don’t forget to stock up on good books before the next lockdown arrives.

Normal service will be resumed in next week’s blog, so until then stay healthy and happy and don’t forget to stock up on good books before the next lockdown arrives.