On the face of it the Brontës lived ordinary lives in an ordinary, if ecclesiastical, lower middle class home in the first half of the nineteenth century – and yet, of course, they achieved extraordinary things. Throughout the year we see Brontë anniversaries occurring, some are some life milestones and dramatic events, others are more mundane, but together they all help to shape our understanding and appreciation of this wonderful family.

This week has been more full of Brontëversaries (apologies for the portmanteau) than most, so in today’s new post we’re going to look at five events which happened in this week on various years, and we’re also going to look at five pictures which shed light on these events.

20th April 1820

Literary history was made on 20th April 1820, although the family concerned could have had no idea of what lay ahead. It was on that day that Reverend Patrick Brontë left Thornton, Bradford to start his new job as parish priest for Haworth, six miles away across the moors. The Brontës had arrived in Haworth and things would never be the same again, for them and the village.

The journey was made in six carriages and one covered wagon which held all their worldly goods – including their most precious cargo of all, three month old baby Anne Brontë. Today people come to Haworth from across the world on a literary pilgrimage, but the village they see has changed greatly from the one they knew. Of course there are no photographs from the time of the Brontë move, there was no photography at all. I like this picture from later in the century of Haworth’s steep and famous Main Street – it was called Kirkgate at the time the Brontës arrived there.

20th April 1817

This particular date holds a double anniversary for in 1817 it witnessed the birth of a woman who would become central to the Brontë story: Ellen Nussey. Ellen was born just one day before the first birthday of the person who became her best friend forever – Charlotte Brontë of course. Despite this Charlotte forgot Ellen’s birthday as she reveals in a letter of 1846:

‘You said I was to think of you on Monday – why? The 20th is not your birthday is it? I thought it was the 22nd.’

Ellen remained loyal to the Brontës to the end, even though she lived for over four decades longer than Charlotte. It was her preservation of the hundreds of letters Charlotte sent to her that means we know so much about the family today, although in Ellen’s later years this also made her vulnerable to conmen who took many of her beloved treasures from her. We have many photographs of Ellen Nussey, mostly from her later years, but I have chosen this one as it was for a long time thought to be of Charlotte Brontë and even appeared centre stage on Charlotte’s Wikipedia page – comparison to other photographs of Ellen however can leave us in no doubt who it really is.

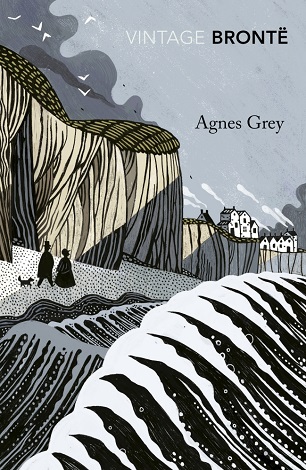

21st April 1816

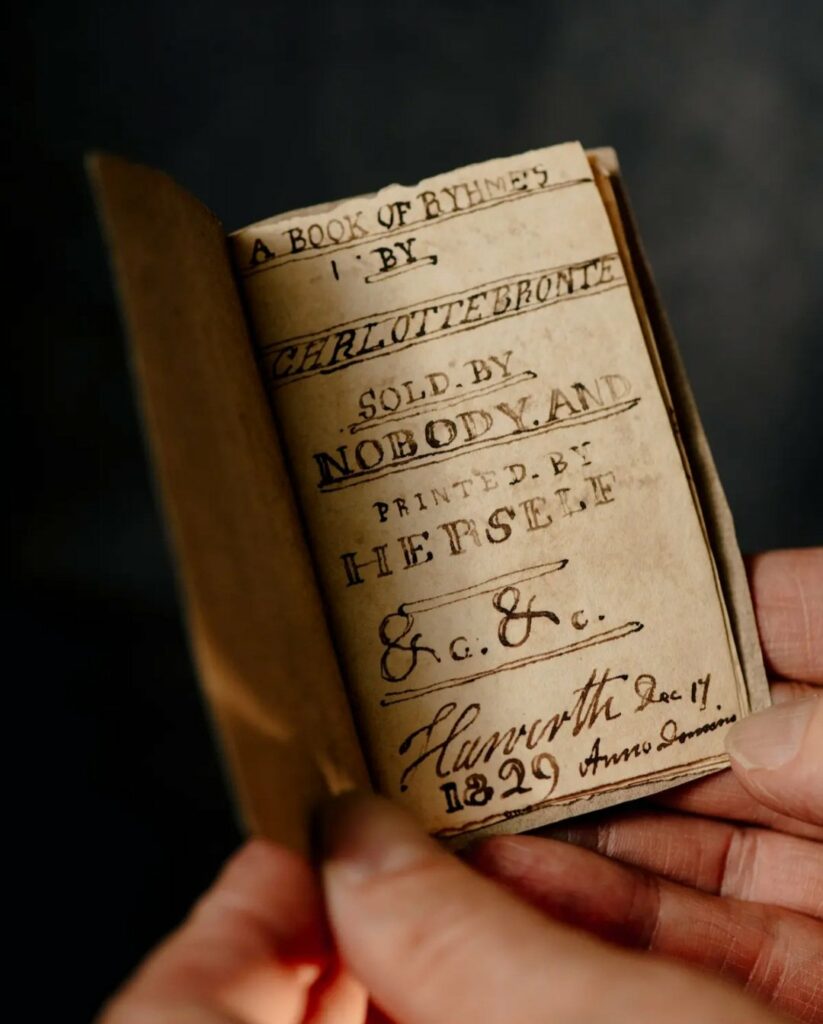

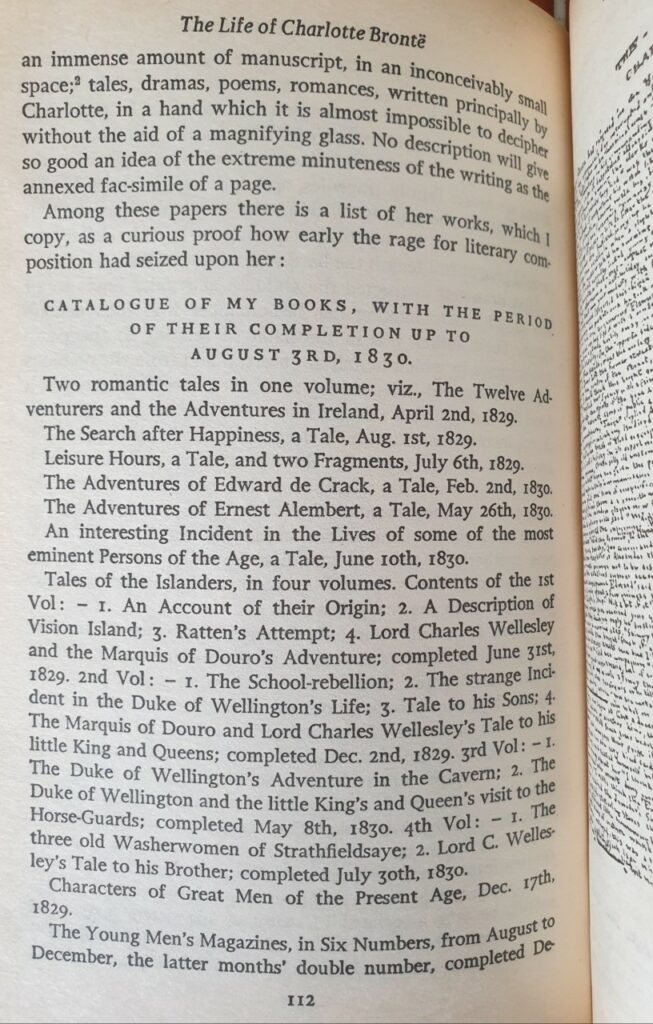

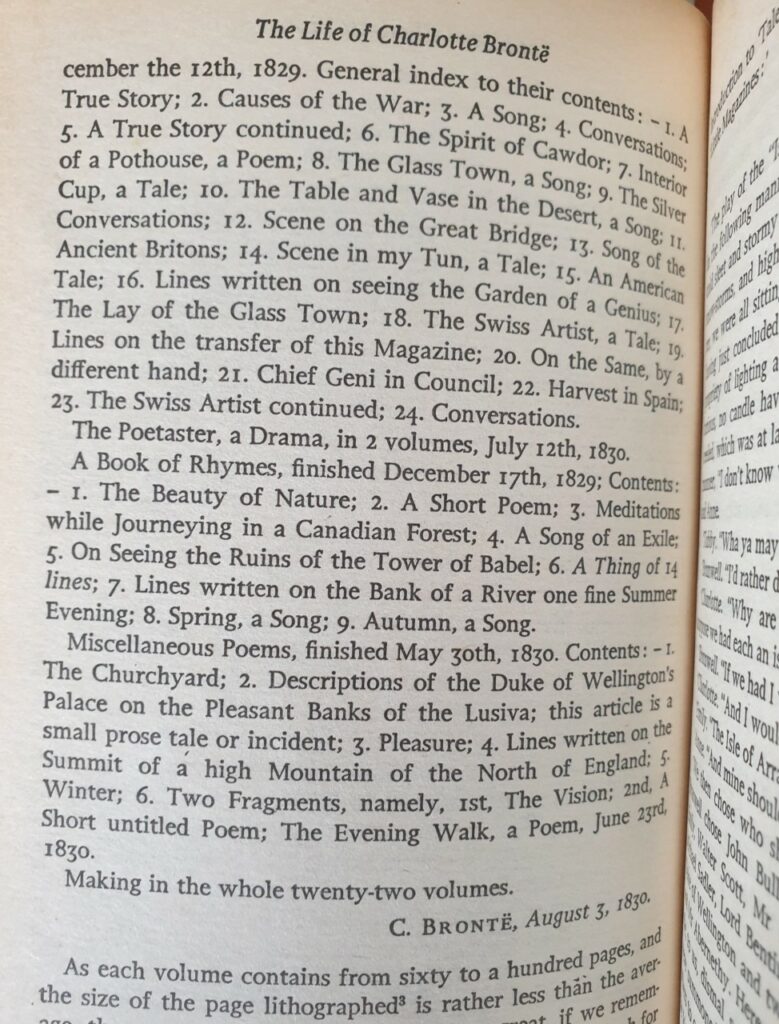

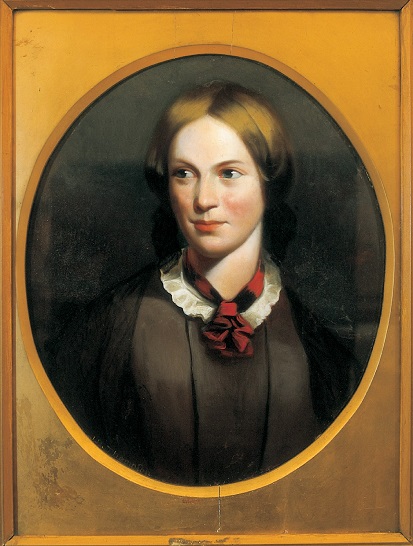

We’ve already touched on this above, but the 21st April marks the anniversary of the birth of one of the towering genii of English literature: Charlotte Brontë. If only she had lived to write more than the four novels we have, what further masterpieces would we now be enjoying?

Charlotte’s life was far from an easy one, losing her mother and then her two eldest sisters in her formative years meaning that she was forced to grow up quickly. In her adult life too she suffered disappointments in work and in love, but it was these personal challenges and tragedies which gave such powerful impetus to her writing. Her friend and fellow literary genius Elizabeth Gaskell was correct when she said that Charlotte ‘had the heart of Robert [the] Bruce within her, and failure upon failure daunted her no more than him.’

We have two portraits of Charlotte that were more of less contemporaneous (as well as the portraits made by her brother Branwell Brontë). George Richmond’s portrait was an official one for which Charlotte sat on a number of occasions, but I’ve chosen this portrait by J. H. Thompson. It was made after Charlotte’s death, but Thompson was a friend of Branwell and had met Charlotte. It is such a pretty portrait, which I feel that Charlotte would have appreciated, and kindness radiates from it, just as it did from Charlotte herself.

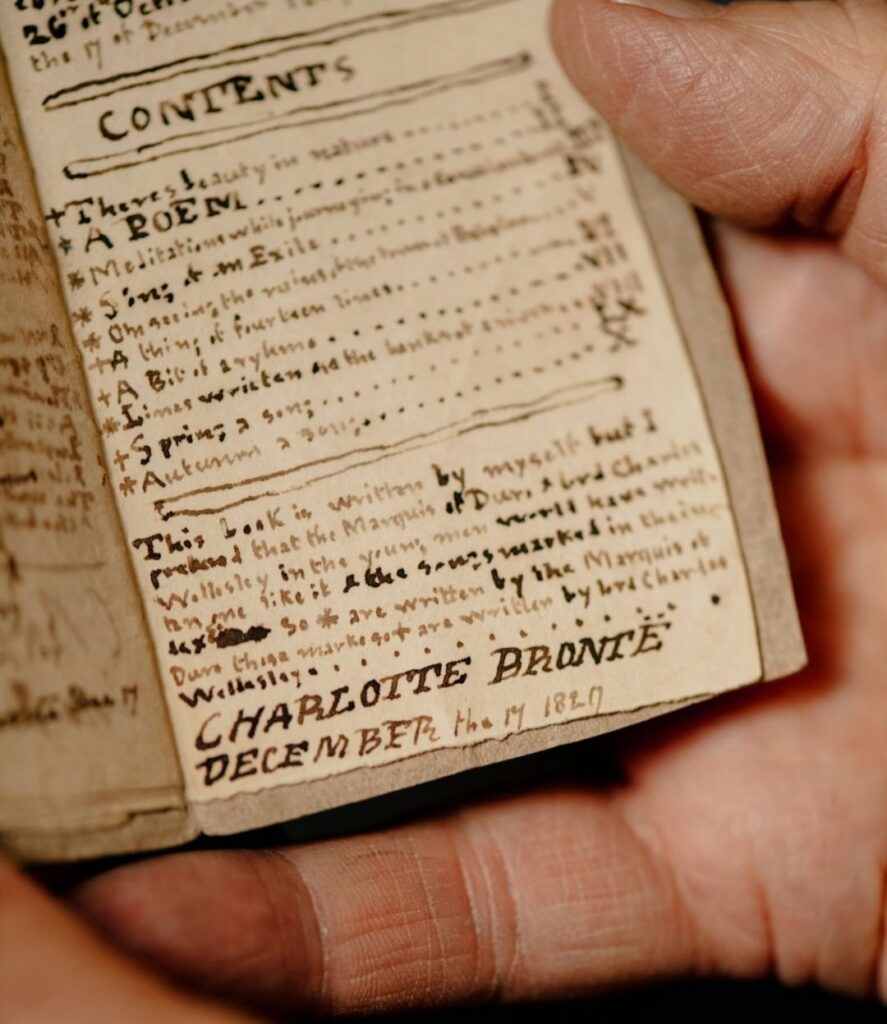

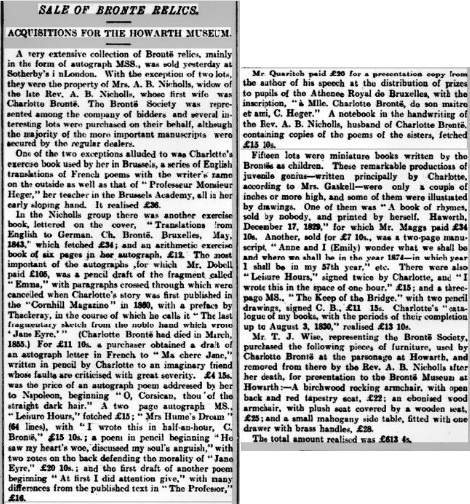

22nd April 1828

Yes, it’s three birthday Brontëversaries in a row, as the 22nd April 1828 was the birthday of Martha Brown. Martha was daughter of Haworth sexton John Brown who lived a short hop from the parsonage. When the Brontës needed a young servant to assist the infirm Tabby Aykroyd, it was to Martha that they turned. She entered the parsonage aged 12 and remained there for over 20 years, until the passing of Reverend Patrick Brontë, the first and last of the Brontës.

Martha was not only a reliable servant and maid, she also became a friend of Charlotte Brontë and a confidante and comfort after the deaths of Branwell, Emily and Anne in rapid succession during 1848 and 1849. Martha later left Haworth to live with Charlotte’s widower Arthur Bell Nicholls and his second wife in Banagher, Ireland (although she visited her family in Yorkshire again at intervals). A Nicholls family relative later recalled Martha’s arrival in Ireland, and said that Arthur brought her across because he and she had witnessed much sorrow and a short-lived happiness together, and he wanted her to have security in her old age. Having said that, Martha was only in her mid thirties, and younger than Arthur, when she joined him across the Irish Sea. Here is a photograph of Martha Brown, and what character it captures in her!

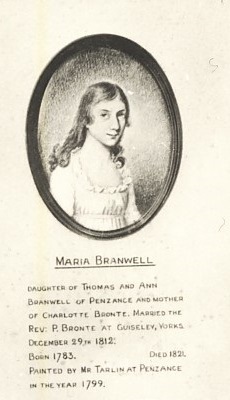

23rd April 1814

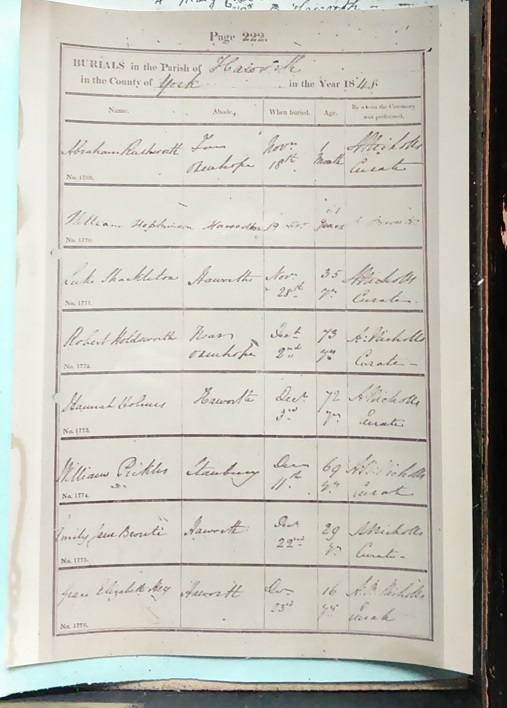

The 23rd of April 1814 can be said to mark the recorded beginning of the Brontë siblings, for it was the date of baptism of Maria Brontë, the first of five sisters and a brother. There is no record of her birthday, in those days before registering a birth became compulsory, so this is the first appearance we have of a girl who would have such a lasting influence on her writing siblings.

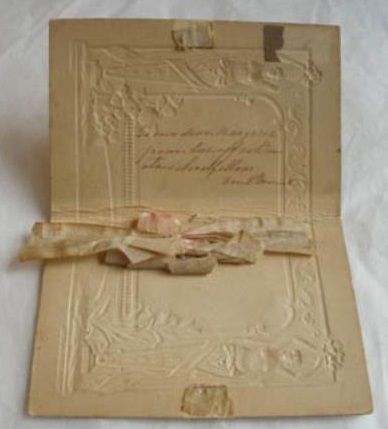

There are many tales of what a precocious talent young Maria was, and Charlotte paid tribute to her under the guise of Helen Burns in Jane Eyre. Alas, that talent did not have the chance to flourish into adulthood, and there are no images of her. What we do have, however, is this: an extremely touching needle case that Maria Brontë gave as a gift to a classmate called Margaret Dixon and which contains the only example we have of her handwriting.

Five Brontëversaries in five images and they all remind us of something very important: we see them today as names on the fronts of books, or names which appear in Brontë biographies, but they were living, breathing people facing the same emotions, challenges and triumphs as we do today. Times and fashions change, but the Brontës weren’t too different from you and I, with one difference – their incredible genius and writing talent.

I will leave you with a bonus image today for it was on this very day in 1939 that James Roosevelt, son of the American President FDR, made his own literary pilgrimage to Haworth Parsonage. This image of him with an old Haworth villager is like two world’s colliding and yet they too probably had more in common than they had differences. I hope to see you again next week for another new Brontë blog post.