June the 29th was a momentous day for Charlotte Brontë at both ends of her life – and for two very different reasons. In 1816 it was the day that she was baptised, whilst in 1854, sadly just a year before her untimely death, it was the day she married.

Charlotte’s baptism took place in the village of Thornton, just over two months after her birth – and there often seems to be a gap between the birth of the Brontë children and their baptisms. It was not at the grand church of St. James that can now be seen at the Thornton but directly opposite it, at what is now known as the Bell Chapel. It is now a ruin, but thanks to local activists a beautiful one.

Presiding over the baptism was Patrick Brontë’s great friend William Morgan, and acting as Charlotte’s godparents were Reverend Thomas Atkinson and his fiance Frances Walker of Lascelles Hall. These two were very instrumental in the Brontë story, as Atkinson was the former curate of Thornton who had suggested to Patrick that they swap parishes (leaving Atkinson with the smaller and less remunerative parish of Hartshead) so that he could be closer to Frances, the woman he loved.

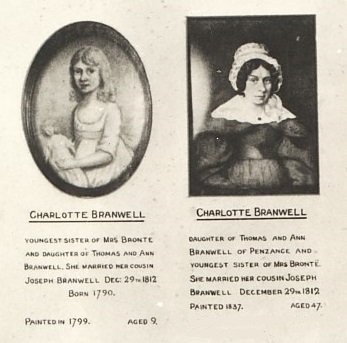

It has been conjectured that Charlotte’s other godmother could have been her aunt Charlotte Branwell, Maria’s younger sister still living in Penzance, for after all another sister was made godmother to the second Brontë sibling who was given her name – Elizabeth. Charlotte Branwell certainly didn’t travel to the ceremony, but Elizabeth Branwell did make the long journey from Penzance to Thornton for the baptism of her niece Elizabeth, and stayed on at Thorton for a year afterwards. She would make another, final, journey north and re-enter the lives of the siblings in 1821 as Aunt Branwell.

None present on that June day in 1816, of course, could have known what the future would hold for the baby in front of them, one of tragedy but also of incredible achievement and triumph, and nor could they have known that another momentous day in Charlotte’s life would come exactly 38 years later.

By 1853, Charlotte was the last Brontë sibling left alive, and she lived at home with her ageing father and their servants Martha Brown and Tabby Aykyroyd. She was 37 that year, and although she was by now a literary success it seemed that she would remain a spinster forever. It was in that year, however, that Arthur Bell Nicholls proposed to her. Nicholls was, like Charlotte’s father, an Irish priest in the Church of England, and he’d served Patrick as assistant curate since May 1845. Over eight years he had fallen in love with the tiny, tormented Charlotte, and one of the duties he now loved to perform was to walk the dogs Keeper and Flossy that Emily and Anne had had to leave behind forever.

His proposal, however, was not well received on either side. Patrick was furious that his assistant had dared to propose marriage to his daughter who he now felt could do much better, and he was also worried about what would happen to him if the daughter he was so reliant upon left. Charlotte herself professed herself not in love with him at all, and said that she barely liked him. Arthur had been building up the courage to make the proposal for months, maybe years, and the rejection hit him hard. He announced that he had applied to become a missionary in Australia and resigned his position at Haworth. On the last but one service he conducted, Charlotte records how he started shaking at the pulpit and then became unable to speak. The congregation had to lead him outside, many of them in tears, and Charlotte herself admits that she herself wept a little. The whole village knew why he was leaving, and on the following week the spectacle happened again. Charlotte writes how she later found him near the church “sobbing as women never sob”.

At this, what they supposed, final meeting Charlotte tried to console him a little, but this seems to have reignited Arthur’s hopes. Instead of going to Australia he moved to another church in Yorkshire, and continued to write to Charlotte. Eventually, his persistence and obvious dedication began to wear Charlotte down, and a year later he returned to Haworth where his second proposal was accepted on the proviso that they would remain at the Haworth Parsonage and continue to look after Patrick.

This acceptance of an engagement now outraged Ellen Nussey, Charlotte’s lifelong friend, as it seems that they had some sort of pact to grow old as spinsters together. Ellen herself would never marry, and nor would her other great friend from her school days Mary Taylor, or her former teacher, employer and now friend Margaret Wooler. For the first time in their lives they ceased writing to each other, but somehow the rift was healed in time for Ellen to act as Charlotte’s bridesmaid.

Charlotte, typically, didn’t want any fuss or extravagance to be made regarding her nuptials, although Ellen eventually forced her to go shopping for bridal wear and made her select a white dress. The beautiful bonnet the bride wore is on display at the Brontë Parsonage Museum, and locals said that she looked ‘like a snowdrop’ as she, Ellen, and Margaret walked the short distance from the Parsonage to the church.

The wedding took place at eight o’clock in the morning on 29th June 1854, and one important man was not to be there. At the last moment Patrick said that he felt too ill to attend, although we’ll never know if this was true or if he was still harbouring some resentment at the marriage itself. Margaret Wooler stepped into the breach and it was she who gave Charlotte away, with Reverend Sutcliffe Sowden, a great friend of Arthur, conducting the ceremony.

Also present at the church were Joseph Grant, a friend of Nicholls, and his wife, Sutcliffe Sowden, the vicar of Hebden Bridge, the sexton John Brown and his daughter Martha, Joseph Redman, the parish clerk, and John Robinson, a local boy and former pupil of Charlotte’s. We can also assume that the by now aged and infirm Tabby Aykroyd would also have been there if she was well enough on the day. It was a low key affair, as Charlotte wanted, and they held a reception afterwards at the Sunday school building that lay between the church and the Parsonage.

To Charlotte’s great surprise she fell in love with her new husband, and on Christmas Day 1854 wrote to Ellen of how happy they were together. It was not to last. Charlotte fell pregnant, but was struck down by extreme morning sickness, then a frequently fatal condition in those days before drips, and died on March 1st 1855.

As Charlotte Brontë married in her late thirties, we can ask whether Emily and Anne may have done the same if they had lived to see those years. I once put this question to a famous Brontë expert, who shall remain nameless although they are in my opinion today’s greatest authority on the Brontës, and they opined that Emily would never have married, as she was in their opinion a little odd and so would never have found a suitor. Anne Brontë, however, they felt may one day have found a husband, if she had ever regained health and overcome her mourning for her one love William Weightman.