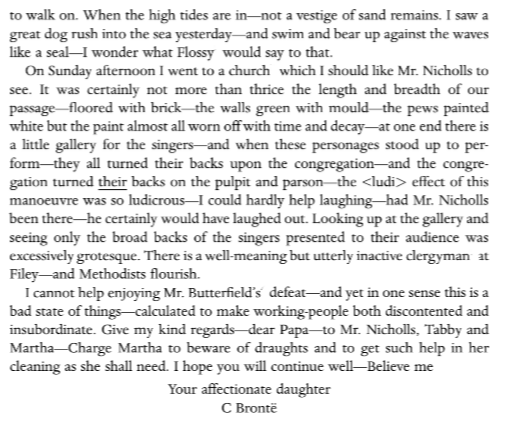

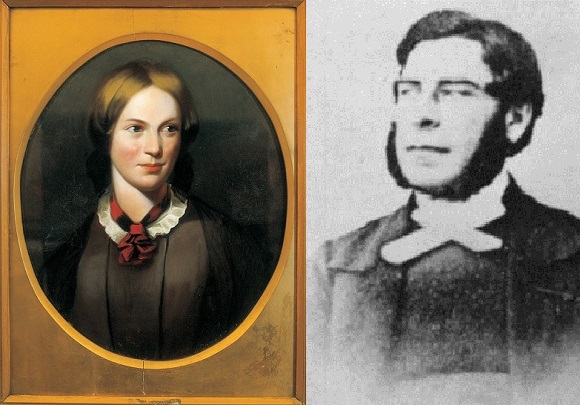

Weddings are beautiful occasions, what could be better than a celebration of that most powerful and important emotion: love. It doesn’t matter whether they are big or small, all weddings are magical. Yesterday marked the 170th anniversary of a wedding where only nine attended, and yet we still know of it today. The bride’s name: Charlotte Brontë. I’ve included some pictures from a Haworth recreation of this wedding throughout this post.

We know details of the wedding thanks to one of the guests of whom many people will know little. He plays no other role in the Brontë story, and was a teenage apprentice at the time of Charlotte’s marriage to Arthur Bell Nicholls, and yet it is thanks to two interviews that John Robinson of Barnsley gave over 60 years later that we know who was in the church on that late June morning in 1854. In today’s Brontë blog post we’re going to take a look at the seven guests who witnessed this intimate wedding ceremony:

“One morning I met the sexton, John Brown, the father of Martha Brown, who said that he had been waiting for me. He told me that Charlotte and Mr. Nicholls were going to get married, and my instructions were to go to the top of a hill and look for the approach of three men. When I saw them I was to run back to the parsonage and tell the folk there that they were coming. I went to my place and watched, and presently I saw in the distance three persons – Mr. Nicholls, Mr. Grant, and Mr. Sowden. Then I went back to the parsonage, and was told to go as fast as I could for Josh Redman, the old parish clerk. I found him, and told him he had to come to church as quickly as possible. He came immediately. On the way he stopped and said, ‘I’d better lace up my boots,’ and he went to the wall and did so. We hurried to the church, and on the stroke of eight Charlotte entered with her two women friends. There were thus in the church Charlotte, her two friends, the clerk, the sexton, and myself – nine persons in all. I don’t think Mr. Brontë was there.”

John Robinson

We will start with the narrator himself. John Robinson was a Haworth-born boy from a poor background. He would have been expected to work in local mills, but his intelligence marked him out from an early age. It was decided to train him up to be a teacher, and he was apprenticed in this trade to the man who ran the local church school: the parish’s assistant curate Arthur Bell Nicholls.

Being young and fit, it was also decided by parish sexton John Brown to use Robinson as runner on this momentous day. Thus Robinson, to his great surprise, on his way to his school was told that Charlotte and Arthur were being wed that morning and to round up the necessary people at the appropriate times. Robinson never forgot Arthur Bell Nicholls, saying of him over six decades later: “No kinder-hearted man or one more anxious to see others improve their position in life, ever lived, and I myself – I might say scores besides – have him to thank for putting us in the way to make a way in life instead of remaining where we had been born, which was undoubtedly at one time one of the poorest places in England.”

John Robinson went on to have a long and successful career as a teacher, leaving Haworth and eventually becoming head of a school in Wombwell, Barnsley. At the time of his newspaper interviews he was himself celebrating his own diamond wedding anniversary!

John Brown

It was undoubtedly John Brown who selected the unwitting Robinson to be Charlotte Brontë’s wedding day runner. He was parish sexton, an important role with functions within St. Michael’s church and in the graveyard stretching away from it. By the time of the wedding he was also the next door neighbour of Charlotte Brontë, living in the building named Sexton House which he himself constructed.

He was also a great friend of the Brontë family, and had been especially close to Branwell Brontë. It was John Brown who took Branwell to Liverpool in an attempt to wean him off his drink and narcotic addictions, and John’s daughter Martha Brown was a live-in servant in the Brontë parsonage. Alas he died in 1855 just a year after the wedding and, double alas, just weeks after the death of Charlotte Brontë.

Sutcliffe Sowden

Sutcliffe Sowden was one of the three men Robinson was told to watch for coming over the hill. (In his other account, Robinson said Brown told him: “We want tha to go to t’top of t’ ‘ill to watch for three parsons coming from t’other hill, coming from Oxenhope. Charlotte and Mr. Nicholls are going to be married, and when tha sees Mr. Nicholls, Mr. Grant, and Mr. Sowden coming at t’ far hill, tha must get back to t’ Parsonage, so’s Charlotte and Ellen Nussey can get their things on to go down to t’ church.”)

Sutcliffe was a close friend of groom Arthur Bell Nicholls and had an important role to perform on that day: it was he who would perform the wedding ceremony. Reverend Sowden was from the Halifax family who had been farmers on land owned by the mistress of Shibden Hall Anne Lister, but it was the pulpit rather than the pigpen which called Sutcliffe. He was the vicar at Hebden Bridge but returned to Haworth to conduct one more ceremony in 1855: the funeral of Charlotte Brontë. Sutcliffe Sowden himself fell into a canal one foggy night in 1861 and drowned.

Joseph Grant

The other close friend accompanying Arthur on his wedding morning was Reverend Joseph Grant. He had been Arthur’s predecessor as assistant curate in Haworth, but Charlotte seems to have taken a dislike to him – in her novel Shirley she used Grant as the model for Reverend Donne, a domineering and self-centred man.

Nevertheless he was loved by Arthur, and as curate of neighbouring parish Oxenhope it was with him that Arthur stayed on the night before his wedding. It eventually became well known that Grant was the model for Donne, and he was often called Mr Donne from then on, but he seems to have taken it in good faith.

Joshua Redman

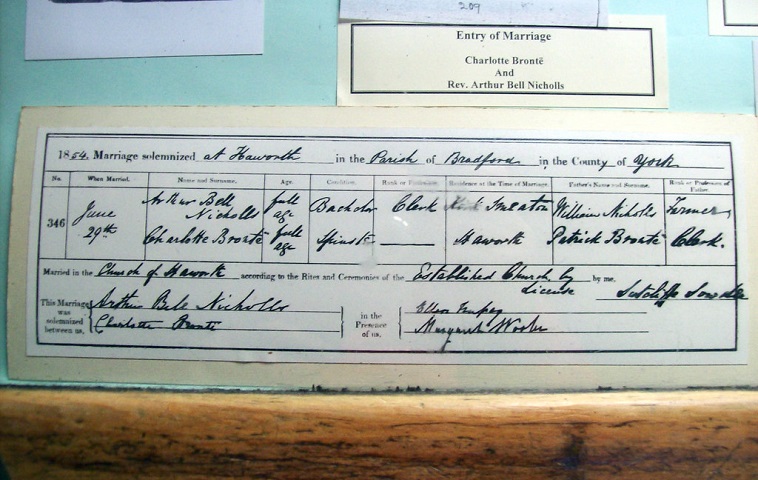

Redman was parish clerk, and it was he who had to sign the papers and declare the wedding legal. It is a measure of the secrecy with which Charlotte and Arthur planned their wedding therefore that even he knew nothing of it until minutes before it was due to take place. His daughter Martha Redman was an occasional helper in Haworth Parsonage during busy times. Redman died aged 66 in 1862.

Ellen Nussey

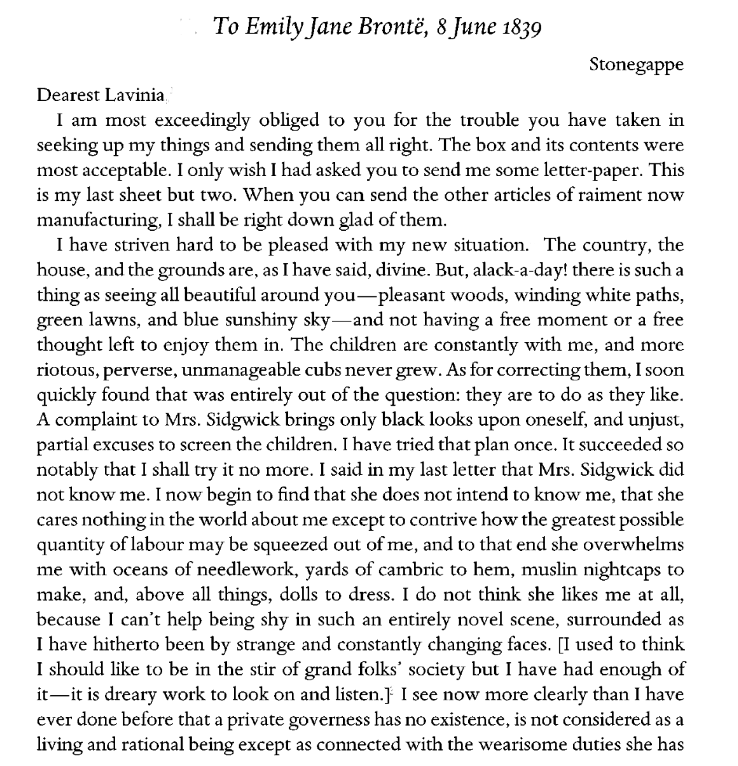

Ellen Nussey was Charlotte Brontë’s great lifelong friend, and yet at first it seemed that the marriage of Charlotte and Arthur would cause a terrible schism between them. After Charlotte wrote to Ellen telling her that she had accepted Arthur’s proposal there was a long break in communications between them. Ellen loved Charlotte dearly, and it could be that she (like Charlotte’s own father Patrick) felt that Arthur was beneath her, or it may be that she had hoped and expected that Charlotte and she would remain single for the rest of their lives.

It took some diplomacy on behalf of the next guest to bring them together again, and Ellen finally agreed to be Charlotte’s bridesmaid. The friendship was restored, and it is thanks to Ellen’s preservation of hundreds of Charlotte’s letters that we know so much about the Brontë story today. Between Ellen and Arthur, however, there was a lasting enmity.

Margaret Wooler

Margaret Wooler was head and founder of Roe Head School, MIrfield when Charlotte Brontë went there as a schoolgirl in 1831. For years later Charlotte came back as a teacher and Margaret was now her employer. It was an at times fractious relationship then, especially as Charlotte was ill suited to the role of teacher, but they became firm and enduring friends.

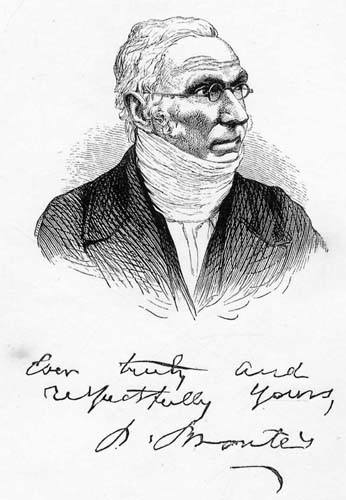

As the day of the wedding arrived it was still unclear whether Patrick Brontë would attend his daughter’s wedding. In the end he declared he was too ill to take the short walk to the church, and to be fair this may have been true as Patrick was 77 by this time and suffering again from sight loss.

Margaret stepped up to the occasion, and it was she who gave Charlotte Brontë away at her wedding. Margaret Wooler and Ellen Nussey were also the two witnesses who signed the wedding certificate for Charlotte and Arthur. Margaret lived to a ripe old age, sharing a house with two of her sisters well into her nineties.

The other two members of the nine were, of course, the bride and groom themselves. Charlotte Brontë and Arthur Bell Nicholls had a happy but all two short marriage – but at least Charlotte Brontë found love and happiness in the last months of her life.

I hope you can join me next Saturday for another new Brontë blog post. That’s right – it’s Saturday not Sunday next week as on 7th July I will be discussing Anne Brontë at the Bradford Literature Festival – you can buy tickets at this link: https://www.bradfordlitfest.co.uk/event/anne-Brontë-and-agnes-grey-parallels-of-resilience-and-reality/