March 17th sees scores of people with Irish blood, and even more without Irish blood but with more than a little guinness running through their veins, head out onto the streets to celebrate St. Patrick’s Day. This year the unseasonal snow storms curtailed many celebrations, and it’s also responsible for this post being a little later than usual – please accept my apologies. Even so it’s time to celebrate a a famous Patrick born on March 17th – and no, he didn’t rid Ireland of snakes.

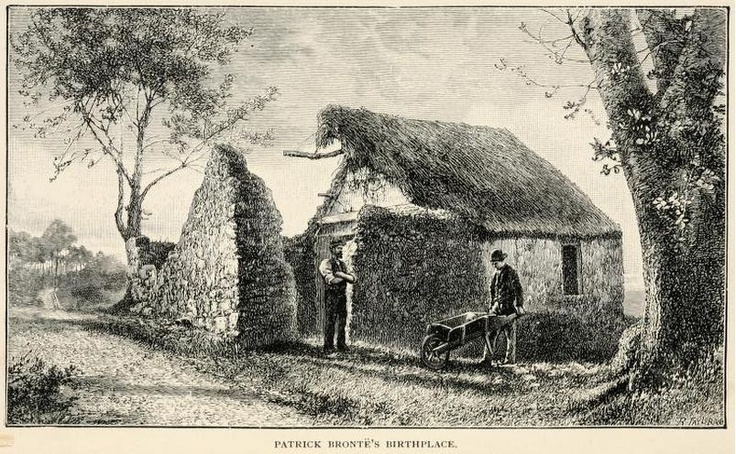

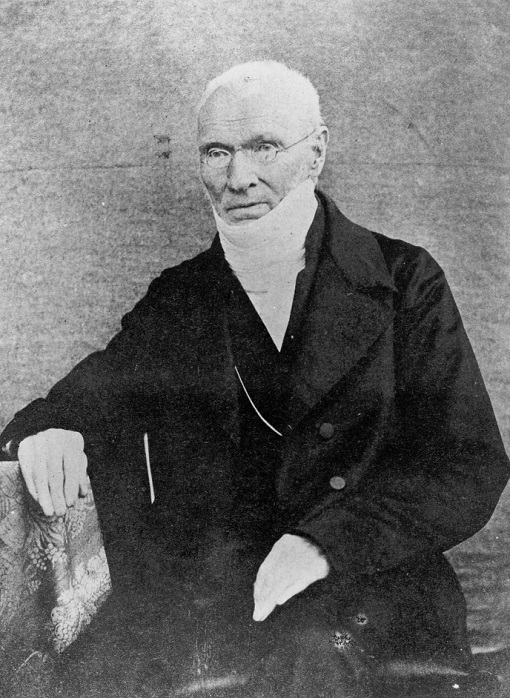

Patrick Brontë, for it is he, was named after the saint’s day upon which he was born in 1777 into a poor family in Emdale, near Drumballyroney in County Down (his house is at the top of this post). Through hard work and a particular talent for learning he escaped his roots and was given a scholarship to Cambridge University. It was here that he adopted the Brontë spelling of his name that would become so famous from his original Prunty or Brunty, thus downplaying both his poor background and his Irishness at a time when anti-Irish prejudice was rife.

The father of the Brontës was a Church of England priest, and an arch Tory in political terms, so it’s little surprise that he was vehemently opposed to Irish home rule. Nevertheless he remained proud of his background and kept in touch with his Irish family all his life. The Pruntys of Ireland are equally proud of their famous ancestor, and we all have a lot to be thankful for, for the way that he raised his daughters especially was ahead of his time and helped smooth the path for the books that we all know and love.

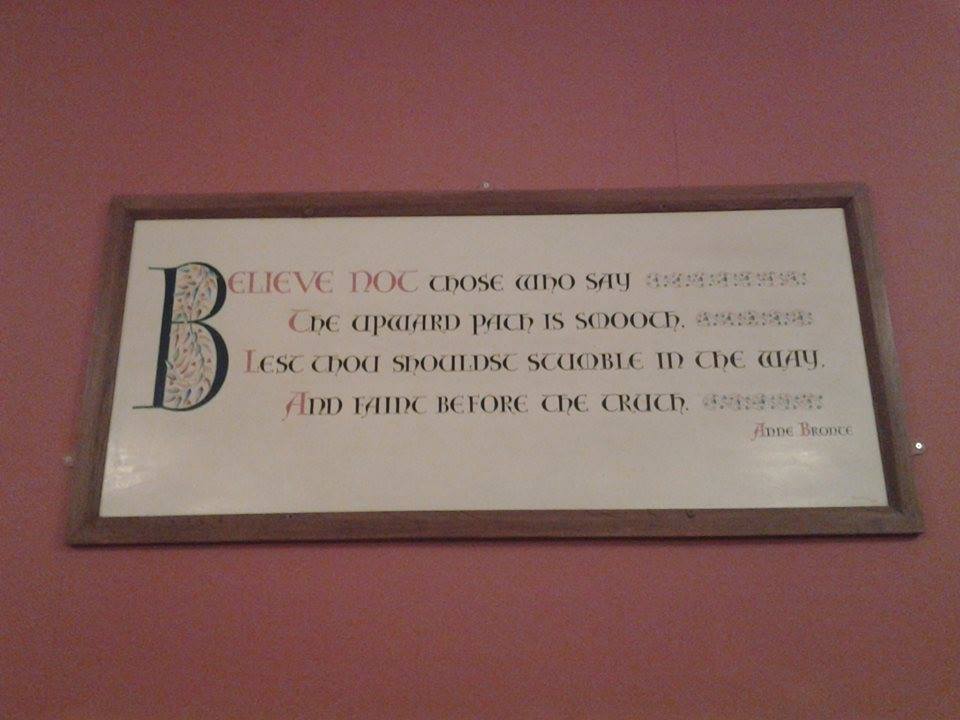

Patrick believed in the power and importance of education, it was this after all that had taken him from a life of hard work and poverty in County Down to the respectable position of Anglican priest in Yorkshire. He wanted other children to have the opportunities he had, which is why he opened Sunday schools in Thornton and in Haworth. Charlotte, Branwell and Anne often had to teach in Haworth’s Sunday School, and it now has a tribute to Anne Brontë upon its wall. We get an image of Anne’s first time teaching in her father’s school in this description of Caroline in Charlotte Brontë’s ‘Shirley’:

‘They made her a Sunday-school teacher when she was a little girl of twelve. She is not particularly self-confident by nature, as you may have observed; and the first time she had to ‘take a tray’, as the phrase is, and make tea in public, there was some piteous trembling and flushing. I observed the speechless panic, the cups shaking in the little hand, and the overflowing teapot filled too full from the urn.’

Patrick was an avid reader, and a published author too, and he allowed his children free access to his library: daughters as well as son. This meant that Anne could read everyone from Shakespeare to Scott, from Byron to Shelley. These last two were particularly controversial, not many early nineteenth century fathers would have allowed his daughters to read the wild Byron or the radical atheist Percy Bysshe Shelley. Patrick Brontë did, and this must have contributed to their intellectual brilliance and writing genius.

There are stories of Patrick being aloof from his children and sometimes cruel to his wife Maria. Certainly Patrick could be reclusive and often liked to eat alone in his study, but this was a trait also found in Charlotte, Anne and especially Emily Brontë. As to the cruelty, I think we can now find him not guilty. There is little doubt that he adored his wife, and he nearly bankrupted himself trying to find vain cures during Maria’s final illness. Every married couple argues from time to time, but stories such as him destroying a pair of Maria’s shoes were taken out of context in Elizabeth Gaskell’s autobiography of Charlotte.

Gaskell’s source was a servant called Martha Wright, who had been hired to nurse Maria Brontë but who was summarily dismissed by Patrick after the arrival of Elizabeth Branwell to the parsonage. She evidently bore a grudge, and Martha is also responsible for the utterly erroneous tale of how Patrick never fed his children meat.

Ellen Nussey, that fine and faithful friend of the Brontë family, was particularly upset at this portrayal of Patrick, and after reading Elizabeth Gaskell’s book she wrote to her accordingly:

‘The anecdote of the little coloured shoes produced a mental sting that no time would obliterate and I felt that all commonplace readers would fail to see the Spartan nature of the act unless you pointed it out to them, and I was intending to ask you to make very clear and distinct comments on Mr. B’s character – I do not wish anything you have said suppressed, only I think your readers will have to be taught to think kindly of Mr. B’

Patrick himself summed up his character succinctly after the death of Charlotte meant that he had outlived all six of his children:

‘I do not deny that I am somewhat eccentric. If I had been numbered among the calm, sedate, concentric men of the world I should not have been as I now am. And I should in all probability never have had such children as mine have been.’

Patrick Brontë was a great man not only in the way that he raised his daughters, but also because it was his continued efforts that finally brought a government health inspector and then a fresh supply of water to Haworth, thereby saving thousands of lives. The reservoirs around Haworth and the novels of his daughters are his legacy, so to this eccentric man we say a belated ‘Happy Birthday, Patrick Brontë!’