If only we could have stepped back in time and arrived back in Haworth in 1854, we would have witnessed a magical event yesterday, for on 29th June the assistant curate of the parish married the parson’s daughter- the happy couple were, of course, Arthur Bell Nicholls and Charlotte Brontë.

I was lucky enough to witness a re-enactment of this wedding a few years ago (that’s it at the head of this post), but there was an earlier re-enactment in 2004 also and, thanks to the Haworth Village website we can enjoy pictures of that grand day, some of which I will use to illustrate this post.

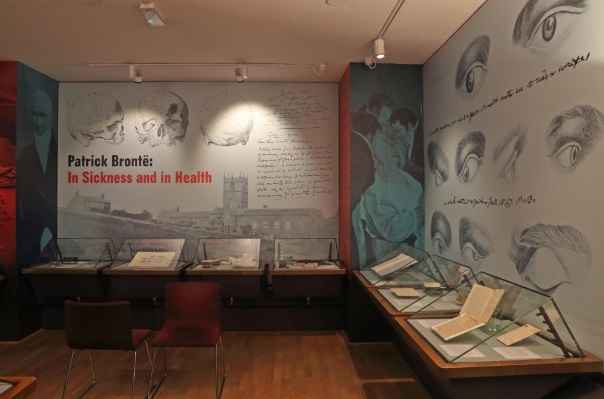

We know quite a bit about the wedding day – how Charlotte was married at eight in the morning, the earliest time a marriage could legally take place, and how soon after the ceremony was completed the bride and groom set off across the moors for a honeymoon in Wales and Ireland. We know how her father Patrick wasn’t feeling well enough to make the short journey to the church, and how Charlotte’s friend and former teacher Margaret Wooler instead took the role of father of the bride and gave Charlotte away. Her bridesmaid was Ellen Nussey, finally reconciled after news of the impending wedding had earlier caused a rare rift between the two great friends.

Arthur was accompanied by his two closest clerical friends, the Reverends Sutcliffe Sowden and James Grant. Sowden conducted the wedding ceremony; Grant had preceded Arthur as assistant curate to Patrick Brontë, and by the time of the wedding had become curate of neighbouring Oxenhope parish. Charlotte was not a fan of Grant and had written to Ellen saying that he would be invited to the wedding breakfast (reception) but not the ceremony itself. I believe, however, that she must have relented and that Grant served as best man, as he accompanied Arthur into the church.

How do I know this? Well yesterday, while thinking about the marriage, I chanced upon a report hidden in a 1913 newspaper. It was with a man who had, as we shall see, played a vital role in the ceremony, although his presence and name have been forgotten in the intervening century. The man, James Robinson, was at the time of the interview a retired headteacher in Wombwell, Barnsley, but in 1854 he had been a 17 year old in Haworth who was being trained to be a teacher by Arthur Bell Nicholls, and he knew the couple well. Robinson gives Arthur a glowing tribute before the account of the wedding, saying ‘I never saw a man feel more than he did’, and ‘no kinder-hearted man or one more anxious to see others improve their position in life, ever lived, and I myself – I might say scores besides – have him to thank for putting us in the way to make a way in life instead of remaining where we had been born.’ This is the side of Arthur those who knew him saw, but one we don’t often think of today.

Robinson’s recollection of the wedding day itself is illuminating and, I think, very moving, and we learn, for one thing, that the Haworth villagers knew nothing of the wedding until it happened. I leave you with his account now, and as we read it we can almost step back in time to that June morning 165 years and a day ago:

“They were married during my apprenticeship. It was not known in the neighbourhood that the marriage was coming off, and to my surprise, when going past the end of ‘Church Fields’ to my lessons one morning, old John Brown, the sexton, was waiting for me, and said: ‘We want tha to go to t’top of t’ ‘ill to watch for three parsons coming from t’other hill, coming from Oxenhope. Charlotte and Mr. Nicholls are going to be married, and when tha sees Mr. Nicholls, Mr. Grant, and Mr. Sowden coming at t’ far hill, tha must get back to t’ Parsonage, so’s Charlotte and Ellen Nussey can get their things on to go down to t’ church.’

I returned with the message, and then was told to get the parish clerk. I found him just beginning to light his kitchen fire, and I had to rush him off, as I knew they would be at the church doors by the time we should get there. He seemed hard of belief. I said, ‘Come on, there’s no time to waste.’

On the way he said, ‘I must stop to lace my boots.’ He did so, and just as the clock was going to strike eight, the three clergymen walked into what they called the front door of the old church and Miss Brontë and Miss Nussey walked together in at the back door.

As far as I remember, the only persons present at the ceremony were those I have named [there was also Margaret Wooler of course]. Directly the ceremony was over, and the interested parties had gone to the parsonage, a carriage and pair drove up from Keighley. There was no station at Haworth then. I remember there was a bay horse and a grey one, and in a few moments Miss Brontë and Mr. Nicholls, now married, were away on their honeymoon. A message came to me to go to the parsonage for breakfast, and I went.”