The summer holidays are fast approaching, as you can tell by the sudden drop in temperature and the dark clouds doing their best to hide that sunny orb from site. If you have children or grandchildren you may be tempted to take them to an art gallery, or you may enjoy that perusing the paintings in your own company. Did the Brontës enjoy art galleries? That’s just what we’re going to look at in today’s new post.

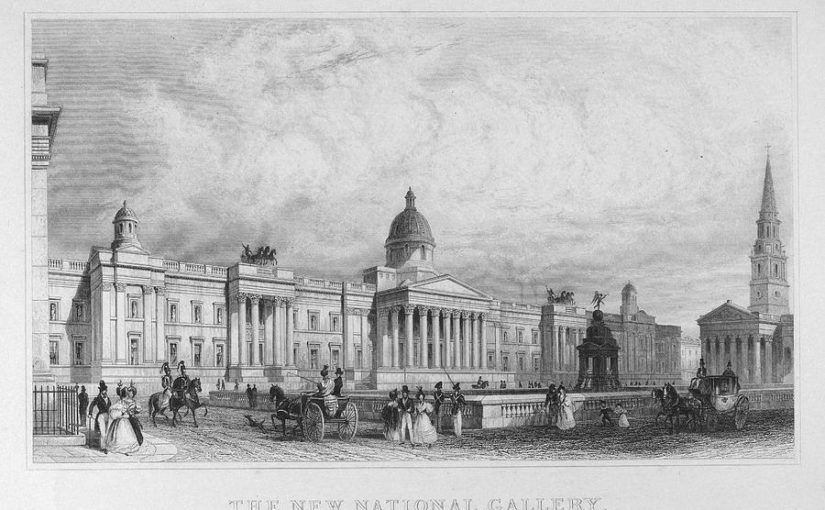

As we know, the Brontës were a very talented family who excelled at just about everything they turned their hand to (especially Emily Brontë, who was a dab hand at everything from bread baking to piano playing and mastering new languages). They were all excellent artists, and of course Branwell Brontë tried to make a career out of it, and was even enrolled to study at the Royal Academy of Arts, although whether he studied there remains a mystery! That’s a picture of it at the top of this post, as it was then part of the National Gallery.

We know that there were definitely Brontë visitors to the gallery however, his sisters Charlotte and Anne! In 1848, those two Brontë sisters travelled to London together. Their mission was to disprove a letter from Charlotte’s publisher George Smith questioning whether Currer and Acton Bell (their pen names) were in fact one and the same person. Presumably they intended to prove their identities, clear up the misunderstanding, clear their names from any suspicions of dishonesty, and then take the train back home to Yorkshire.

Smith, however, was so taken aback by the two genii before him that he insisted on showing them the sites of London and making them guests of himself and his mother. It was the only time Anne Brontë travelled outside of Yorkshire, and she and Charlotte were treated like royalty and shown many of the great sites England’s capital had to offer.

After their return to Haworth, Charlotte Brontë wrote to W. S. Williams (Smith’s assistant at the publishing house): “I wish you had been with us when we went over the Exhibition and the National Gallery – a little explanation from a judge of Art would doubtless have enabled us [Charlotte and Anne] to understand better what we saw; perhaps, one day, we may have this pleasure.”

Charlotte was indeed to have the pleasure of meeting Williams, and Smith, on many further occasions, but alas for Anne it was not to be. This little snippet from a letter shows that Charlotte and Anne loved art, and loved galleries. We get a full glimpse of Charlotte’s love of galleries, however, in her magnificent novel Villette. Like most Brontë novels it has autobiographical elements in it, and particularly of interest to us today is chapter 19 of that work, entitled ‘The Cleopatra’, in which Charlotte, er I mean Lucy Snowe, has visited a Belgian art gallery. The following extract is revealing:

“It was hardly possible to oblige Dr. John quietly and in secret. When you thought that the fabrication of some trifle dedicated to his use had been achieved unnoticed, and that, like other men, he would use it when placed ready for his use, and never ask whence it came, he amazed you by a smilingly-uttered observation or two, proving that his eye had been on the work from commencement to close: that he had noted the design, traced its progress, and marked its completion. It pleased him to be thus served, and he let his pleasure beam in his eye and play about his mouth.

This would have been all very well, if he had not added to such kindly and unobtrusive evidence a certain wilfulness in discharging what he called debts. When his mother worked for him, he paid her by showering about her his bright animal spirits, with even more affluence than his gay, taunting, teasing, loving wont. If Lucy Snowe were discovered to have put her hand to such work, he planned, in recompense, some pleasant recreation.

I often felt amazed at his perfect knowledge of Villette; a knowledge not merely confined to its open streets, but penetrating to all its galleries, salles, and cabinets: of every door which shut in an object worth seeing, of every museum, of every hall, sacred to art or science, he seemed to possess the “Open! Sesame.” I never had a head for science, but an ignorant, blind, fond instinct inclined me to art. I liked to visit the picture-galleries, and I dearly liked to be left there alone. In company, a wretched idiosyncracy forbade me to see much or to feel anything. In unfamiliar company, where it was necessary to maintain a flow of talk on the subjects in presence, half an hour would knock me up, with a combined pressure of physical lassitude and entire mental incapacity. I never yet saw the well-reared child, much less the educated adult, who could not put me to shame, by the sustained intelligence of its demeanour under the ordeal of a conversable, sociable visitation of pictures, historical sights or buildings, or any lions of public interest. Dr. Bretton was a cicerone after my own heart; he would take me betimes, ere the galleries were filled, leave me there for two or three hours, and call for me when his own engagements were discharged. Meantime, I was happy; happy, not always in admiring, but in examining, questioning, and forming conclusions. In the commencement of these visits, there was some misunderstanding and consequent struggle between Will and Power. The former faculty exacted approbation of that which it was considered orthodox to admire; the latter groaned forth its utter inability to pay the tax; it was then self-sneered at, spurred up, goaded on to refine its taste, and whet its zest. The more it was chidden, however, the more it wouldn’t praise. Discovering gradually that a wonderful sense of fatigue resulted from these conscientious efforts, I began to reflect whether I might not dispense with that great labour, and concluded eventually that I might, and so sank supine into a luxury of calm before ninety-nine out of a hundred of the exhibited frames.

It seemed to me that an original and good picture was just as scarce as an original and good book; nor did I, in the end, tremble to say to myself, standing before certain chef-d’œuvres bearing great names, “These are not a whit like nature. Nature’s daylight never had that colour: never was made so turbid, either by storm or cloud, as it is laid out there, under a sky of indigo: and that indigo is not ether; and those dark weeds plastered upon it are not trees.” Several very well executed and complacent-looking fat women struck me as by no means the goddesses they appeared to consider themselves. Many scores of marvellously-finished little Flemish pictures, and also of sketches, excellent for fashion-books displaying varied costumes in the handsomest materials, gave evidence of laudable industry whimsically applied. And yet there were fragments of truth here and there which satisfied the conscience, and gleams of light that cheered the vision. Nature’s power here broke through in a mountain snow-storm; and there her glory in a sunny southern day. An expression in this portrait proved clear insight into character; a face in that historical painting, by its vivid filial likeness, startlingly reminded you that genius gave it birth. These exceptions I loved: they grew dear as friends.

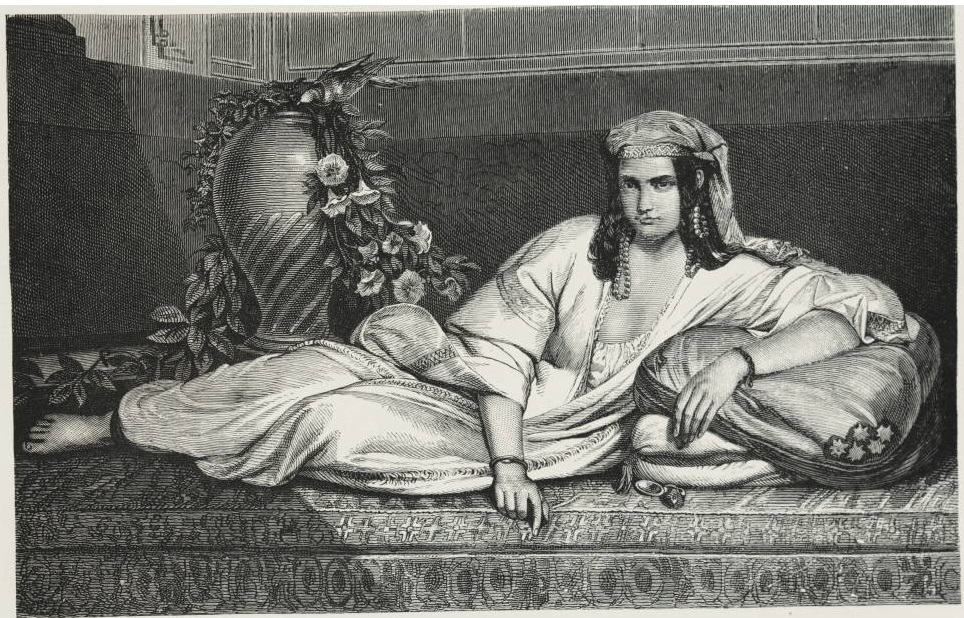

One day, at a quiet early hour, I found myself nearly alone in a certain gallery, wherein one particular picture of portentous size, set up in the best light, having a cordon of protection stretched before it, and a cushioned bench duly set in front for the accommodation of worshipping connoisseurs, who, having gazed themselves off their feet, might be fain to complete the business sitting: this picture, I say, seemed to consider itself the queen of the collection.

It represented a woman, considerably larger, I thought, than the life. I calculated that this lady, put into a scale of magnitude, suitable for the reception of a commodity of bulk, would infallibly turn from fourteen to sixteen stone. She was, indeed, extremely well fed: very much butcher’s meat—to say nothing of bread, vegetables, and liquids—must she have consumed to attain that breadth and height, that wealth of muscle, that affluence of flesh. She lay half-reclined on a couch: why, it would be difficult to say; broad daylight blazed round her; she appeared in hearty health, strong enough to do the work of two plain cooks; she could not plead a weak spine; she ought to have been standing, or at least sitting bolt upright. She, had no business to lounge away the noon on a sofa. She ought likewise to have worn decent garments; a gown covering her properly, which was not the case: out of abundance of material—seven-and-twenty yards, I should say, of drapery—she managed to make inefficient raiment. Then, for the wretched untidiness surrounding her, there could be no excuse. Pots and pans—perhaps I ought to say vases and goblets—were rolled here and there on the foreground; a perfect rubbish of flowers was mixed amongst them, and an absurd and disorderly mass of curtain upholstery smothered the couch and cumbered the floor. On referring to the catalogue, I found that this notable production bore the name “Cleopatra.”

Well, I was sitting wondering at it (as the bench was there, I thought I might as well take advantage of its accommodation), and thinking that while some of the details—as roses, gold cups, jewels, &c., were very prettily painted, it was on the whole an enormous piece of claptrap; the room, almost vacant when I entered, began to fill. Scarcely noticing this circumstance (as, indeed, it did not matter to me) I retained my seat; rather to rest myself than with a view to studying this huge, dark-complexioned gipsy-queen; of whom, indeed, I soon tired, and betook myself for refreshment to the contemplation of some exquisite little pictures of still life: wild-flowers, wild-fruit, mossy wood-nests, casketing eggs that looked like pearls seen through clear green sea-water; all hung modestly beneath that coarse and preposterous canvas.”

Here we have Lucy’s impression of art in a nutshell, she shies away from the large portrait of the Cleopatra, and instead prefers the delicate paintings of flowers. It is surely Charlotte’s own impression too, as we have many examples of her own small and exquisitely drawn pictures of flowers.

So, was this scene in Villette drawn from real life? I believe so, and (as Roy Walker used to say on Catchphrase) the clues are there in the passage above. An early Brontë biographer attempting to establish the veracity of this vividly painted scene opined that it was a real work by a Belgian artist named ‘Defiefve’, and this has been used in many Brontë biographies since, including recent ones – but in fact it’s wrong.

The original attribution had misread a handwritten guide to an exhibition at the Brussels Salon in 1842 – during the time Charlotte Brontë was studying there. The artist was in fact not called Defiefve but De Biefve.

Eduoard De Biefve was one of the leading Belgian paintings of his time, known for his portraits and paintings of historical scenes. He painted some of the leading people of Europe at the time, but one particular work of his caused a scandal in 1842 – when it was exhibited at the Brussels Salon.

This was a huge portrait of an oriental dancing girl, draped across a couch with flowers in the background. It was roundly condemned at the time for being too sexual, and I believe this is the painting Charlotte Brontë saw, was repulsed by and which later inspired the Cleopatra of her novel. De Biefve’s painting is actually called ‘The Almeh’ (a dancing girl or belly dancer) although it is also sometimes called ‘The Sultan’s Favourite Songstress’, and here it is in a black and white reproduction:

That, however, isn’t the only item drawn from nature and disguised by a different name in this scene, or in the book as a whole. At the start of the extract Charlotte is discussing the character of Dr. John Bretton, the man who has brought her to the exhibition. His is a complex character within an admittedly complex, deep novel full of symbolism. At times he is almost a brother to Lucy Snowe, at other times she seems to love him, at others to hate his weaknesses and his attentions to another woman. And yet, all he wants to do is make Lucy happy – he takes her to galleries, museums, to the centres of arts and science. He is in fact very like someone whom Charlotte knew very well: the aforementioned George Smith.

At the time Charlotte knew him and wrote Villette, Smith was living with his widowed mother. They made it their duty to entertain Charlotte to the full when she was in London, and his memoir is full of examples of such enterprises. Sometimes he would leave her whilst he went off to conduct his own business, just as Dr. John does with Lucy at the gallery. In Smith’s memoir we have this recollection of him taking Charlotte to the Houses of Parliament:

“On one occasion I took Miss Bronte to the Ladies Gallery of the House of Commons. The Ladies’ Gallery of those days was behind the Strangers’ Gallery, and from it one could see the eyes of the ladies above, nothing more. I told Miss Brontë that if she felt tired and wished to go away, she had only to look at me – I should know by the expression of her eyes what she meant – and that I would come round for her. After a time I looked and looked. There were many eyes, they all seemed to be flashing signals to me, but much as I admired Miss Brontë’s eyes I could not distinguish them from the others. I looked so earnestly from one pair of eyes to another that I am afraid that more than one lady must have regarded me as a rather impudent fellow. At length I went round and took my lady away. I expressed my hope that I did not keep her long waiting, and said something about the difficulty of getting out after I saw her signal. ‘I made no signal,’ she said. ‘I did not wish to come away. Perhaps there were other signals from the Gallery.’”

It seems clear then that Dr. Breton is a facsimile of George Smith, and of Charlotte’s complex feelings towards him. Smith himself addresses this later in his memoirs:

“In ‘Villette’ my mother was the original of ‘Mrs. Bretton’; several of her expressions are given verbatim. I myself, as I discovered, stood for ‘Dr. John.’ Charlotte Brontë admitted this to Mrs. Gaskell, to whom she wrote: ‘I was kept waiting longer than usual for Mr. Smith’s opinion of the book [Villette], and I was rather uneasy, for I was afraid he had found me out, and was offended.’”

The Brontës loved art and they loved galleries, and I love reading their books and plucking out little moments that seem to be inspired by real life or that have a particular ring of truth or emotion to them – I’m sure you do as well.

I mentioned last week that I would be migrating this site to a new platform, and that is still my plan but it’s taking a little longer than I anticipated. Whatever platform it’s being hosted on, and whatever it looks like, I hope you will join me next week for another new Brontë blog post.