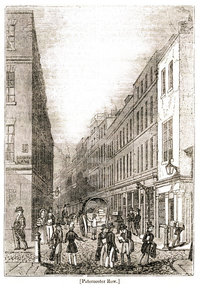

“The heavy, walnut door creaked on its hinges in the Paternoster Row office, and candles flickered around a room that was as gloomy within as the fog drenched street without.

‘A letter for you, Mr Aylott’, a shy, quiet voice intoned before placing the missive on the wax stained table before him as proof of his assertion.

‘Thank you, Mr Jones’, replied the older man who looked as if the red leather chair around him had fitted itself to his form over a succession of sedentary years. He took the letter by one corner and opened it carefully, as carefully as if he were negotiating a deal with a prospective new writer. The paper inside the envelope was tiny, the writing upon it tidier with words cut short to save on space. This was not a letter with a prosperous origin. He read:

‘C. E. & A. Bell are now preparing for the Press a work of fiction – consisting of three distinct and unconnected tales which may be published either together as a work of 3 vols. of the ordinary novel-size, or separately as single vols – as shall be deemed most advisable. It is not their intention to publish these tales on their own account.’

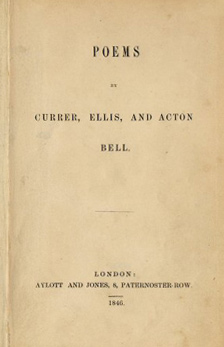

‘It is a letter from Currer Bell, of that northern family whose poetry we recently published, Mr Jones – they propose novels to us.’

‘But we do not publish novels, Mr Aylott?’

‘No, we haven’t sunk quite that far yet, Mr Jones. This Bell is clearly a chap in need of money, in need of help. I will send them a list of publishers of novels – it may be of no use to them, but when means are scarce, hope can be a welcome dish.’”

***

Forgive me my momentary reverie there; I was imagining a scene that might have played out on this very week 173 years ago, for on 6th April 1846 Charlotte Brontë, still using her pen name of Currer Bell, sent the letter mentioned above to Messrs Aylott and Jones of London. It was a letter that went unheralded at first, but it was to change literary history forever, as it showed that the Bell brothers, by which of course we mean the Brontë sisters, had turned their attention from poetry to novels.

Aylott & Jones had recently published the sisters’ brilliant collection of poetry, ‘Poems by Currer, Ellis and Acton Bell‘; it had gained positive reviews, where it had been reviewed at all, but sales had been poor, and the sisters seemingly had little hope of recouping the £35 or so they had paid the publisher to see their work in print.

Many people would have given up in despair at this point, or at least been greatly discouraged, but thankfully for us all, our favourite Haworth family were made of sterner stuff. They realised that their writing was good, but the form they had placed before the public was wrong. The early decades of the 19th century was the golden era of the Romantic Poetry movement, and sales of verse had been strong, but by the time the Brontës were writing they were already in steep decline. The slump was so pronounced that even legendary poets such as Elizabeth Barret Browning and William Wordsworth were finding it hard to persuade great poetry publishers such as Edward Moxon to publish new volumes of their work.

With this in mind, Charlotte, Emily and Anne decided to return to an old love: prose. Their juvenilia is full of sparkling prose (although sadly Anne and Emily’s Gondal prose is now lost) and was a prodigious output, and these years spent honing the craft of novel writing in childhood and youth were to pay dividends.

In her ‘Biographical Notice’ of her sisters, Charlotte Brontë explained what happened next:

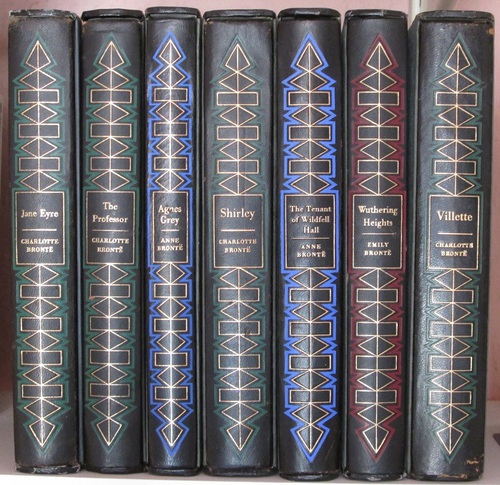

‘Ill-success failed to crush us: the mere effort to succeed had given us a wonderful zest to existence; it must be pursued. We each set to work on a prose tale: Ellis Bell produced ‘Wuthering Heights’, Acton Bell, ‘Agnes Grey’, and Currer Bell also wrote a narrative in one volume. These MSS. [manuscripts] were perseveringly obtruded among various publishers for the space of a year and a half; usually, their fate was an ignominious and abrupt dismissal.’

Did Emily and Anne set to work on their ‘prose tales’ after the failure of their poetry enterprise as indicated above? The evidence seems to suggest they may already have been working on them for some time. ‘Wuthering Heights’ appears highly influenced by the strange but true story of Law Hill school in Halifax, where Emily taught in 1838, and the nearby High Sunderland Hall is often thought of as an inspiration for the titular building of the novel.

In her diary paper of July 1845, Anne Brontë wrote:

‘I have begun the third volume of passages in the life of an Individual. I wish I had finished it.’

It seems to me that this ‘life of an Individual’ is likely to be a prototype of ‘Agnes Grey’. Emily and Anne may have long been working on their novels then, and eventually they found favour with the publisher Thomas Cautley Newby, although, just as Aylott & Jones had done, he asked for the writers to pay a fee to enable publication.

Charlotte’s letter had stated that they would not be prepared to pay any such fee this time, but after a year and a half of rejections, their stance had softened somewhat. The fee was paid and these brilliant books were accepted. If we look at Charlotte’s biographical notice again, we see that she refers to her own contribution to the scheme with the dismissive words, ‘Currer Bell also wrote a narrative in one volume.’

Charlotte’s ‘The Professor’ found no takers until after her death, but once again she didn’t give up and wrote a further novel in great haste, starting in the gloom bestrewn streets of Manchester (some things never change) while she nursed her father after his eye operation. Written at great speed, but full of genius. Elizabeth Gaskell explained what happened:

‘She had the heart of Robert Bruce within her, and failure upon failure daunted her no more than him. Not only did ‘The Professor’ return again to try his chance among the London publishers, but she began, in this time of care and depressing inquietude – in those grey, weary, uniform streets, where all faces, save that of her kind doctor, were strange and untouched with sunlight to her, – there and then, did the genius begin Jane Eyre‘.

That letter of April 1846 then is one we should all cherish, for from it came immortal works of beauty and power. What was unheralded and unloved has become adored the world over, and will be while the sands of time still run.