We are in the middle of a period known as the Brontë 200, marking the 200th anniversaries of the births of Charlotte, Branwell, Emily and Anne Brontë, but today is a special day of an altogether different kind – the 100th anniversary of the end of World War One. At 11am on the 11th day of the 11th month in 1918 the armistice came into place and the guns of the western front fell as silent as the men who lay buried beneath it; it was the war to end all wars, they said, but of course they were wrong.

The Brontës grew up in a time of relative peace on the international stage for Britain, although their parents’ generation had grown up when we were embroiled in the Napoleonic wars, so they heard story after story of legendary military leaders like Arthur Wellesley, the Duke of Wellington, and Admiral Horatio Nelson, whose Brontë fiefdom in Sicily had inspired their own surname.

The Duke became a particular hero of Charlotte Brontë, and it was with some awe that she later met him, then in his eighties, in London’s Chapel Royal in 1850, describing him as a ‘real grand old man’.

The love of Wellington and military stories is also apparent in the Brontë juvenilia, and helped fuel the ‘scribblomania’ which later led to the Brontë novels we so love.

Ellen Nussey, the great friend of the siblings, gave an interesting description of Patrick Brontë, when she said that: ‘he simply had missed his vocation: he should have been a soldier, and circumstances made him a priest.’

There was another Brontë who found themselves compared to a soldier, as this touching recollection of Emily by Haworth stationer and family friend John Greenwood shows:

“Patrick had such unbounded confidence in his daughter Emily that he resolved to learn her to shoot too. They used to practice with pistols. Let her be ever so busy in her domestic duties, whether in the kitchen baking bread at which she had such a dainty hand, or at her studies, rapt in a world of her own creating – it mattered not; if he called upon her to take a lesson, she would put all down. His tender and affectionate ‘Now, my dear girl, let me see how well you can shoot today’, was irresistible to her filial nature and her most winning and musical voice would be heard to ring through the house in response, ‘Yes, papa’ and away she would run with such a hearty good will taking the board from him, and tripping like a fairy to the bottom of the garden, putting it in its proper position, then returning to her dear revered parent, take the pistol which he had primed and loaded for her… She would take the weapon with as firm a hand, and as steady an eye as any veteran of the camp, and fire. Then she would run to fetch the board for him to see how she had succeeded. And she did get so proficient, that she was rarely far from the mark. His ‘how cleverly you have done, my dear girl’, was all she cared for. ‘Oh!’ He would exclaim, ‘she is a brave and noble girl. She is my right-hand, nay the very apple of my eye!’”

Perhaps it was Emily’s prowess with a pistol, as well as her strong, unbending nature, that earned her the nickname ‘The Major’? There were, however, two military relatives among the extended Brontë-Branwell family and their descendants.

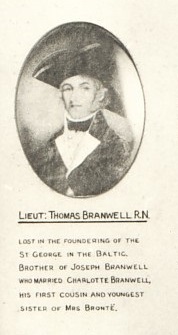

Lieutenant Thomas Branwell was a cousin of Maria and Elizabeth Branwell, and his closeness to them is shown by the fact that he features with them in a series of miniature portraits painted by James Tonkin of Penzance, alongside pictures of Brontë grandparents Thomas and Anne Branwell, and their youngest aunt Charlotte Branwell. He is pictured in all his navy finery, and looks every inch an early nineteenth century military man. He must have been the pride of the Branwell’s but terrible news came at the end of 1811, as reported by the Navy Chronicle of January 1812:

‘The St. George, Defence, and Cressey, kept the North Sea five days, in a dreadful gale from the W.N.W. west and south; but, at length, had to combat with a terrible tempest from the N.W. until they were lost. The following is a list of the principal officers who were on board the St. George and Defence when those vessels were wrecked – In the St. George Admiral Reynolds, Captain Guion, Lieutenants Napier, Place, Thompson, Brannel, Dance, Tristram, Riches, and Rogers.’

Brannel was of course Thomas Branwell, who died at sea on board HMS George off the coast of Denmark. It was a naval tragedy on a horrendous scale, with 731 of the 738 man crew losing their lives and many hundreds more dying on board the Defence. The place where the bodies washed up at Thorsminde, Denmark is now known as ‘Dead Men’s Dunes’.

When we think of the dead today our minds will turn, understandably to those who perished in World War One, but many lost their lives, like Lieutenant Branwell, during the Napoleonic Wars and earlier conflicts too. It is rumoured that he and his cousin Elizabeth were in love, and that he it was that had bought her the elaborately decorated box which she later left to her nephew Branwell. If so this may explain why Aunt Branwell remained resolutely single for the rest of his life.

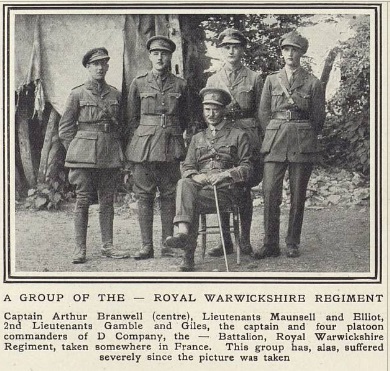

Another Branwell served a long career in the military and survived, Captain Arthur Milton Cooper Branwell. He was a veteran of the army who had been recalled at the start of World War 1, and had fought in the Boer War among other conflicts. We may think that a soldier in ‘The Great War’ must be a very distant relative of the Brontës, but in fact he was a very close one. Born in 1862, he was a first cousin once removed of the Brontë sisters – his father Thomas Brontë Branwell was the Brontë cousin who visited Charlotte and Patrick in Haworth in 1851, and his grandmother was Charlotte Branwell, after whom Charlotte Brontë was named.

During World War One he was a Captain in the Royal Warwickshire Regiment’s 4th Brigade. The following picture appeared in The Tatler of 23rd August 1916 when fighting on the Western Front was approaching its fiercest. As the senior officer, the grand looking Captain Branwell is seated at the centre, but as noted by the caption many of the officers around him were by then dead.

Captain Branwell himself escaped the horrors of the trenches however, as the 4th Brigade was the Royal Warwickshire’s Extra Reserve, and in fact it never left England during the duration of the war. He was heavily involved in training new recruits, and was ready and willing to fight in France if called upon, despite being then in his mid fifties; as the Tatler picture shows, Captain Branwell did arrive in France himself during the conflict, where he would have again taken a training role, passing on his wealth of experience on military matters.

Thomas Branwell paid the ultimate price, and Arthur Branwell was willing to do so, because they believed in their country, and they believed in the importance of freedom from tyranny – many millions then and since have followed a similar path, and today, and all days, we should and will remember them.