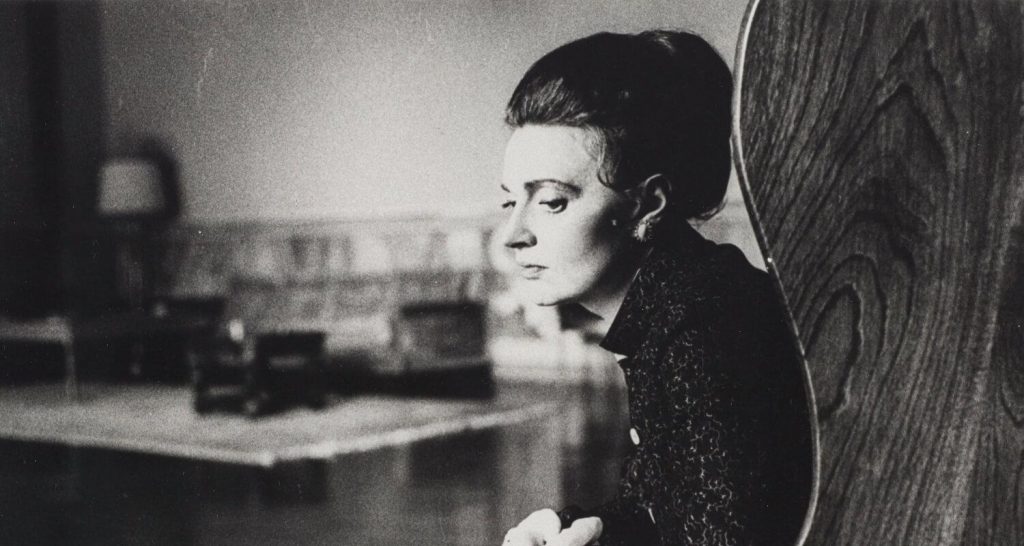

This week saw the launch of ‘Making Thunder Roar’, the year long exhibition at the Brontë Parsonage Museum that aims to celebrate the life of Emily Brontë. I was in Glasgow at the time, taking in celebrations of Muriel Spark’s 100th birthday, but I hope to make it up to the parsonage in the near future – and of course I hope they’ve done Emily proud by putting her front and centre of the exhibition as her great talent deserves. Muriel Spark was an excellent writer herself, of course, with ‘The Prime Of Miss Jean Brodie’ just one of her brilliant books. She was also a huge Brontë enthusiast, leading her to write her own book on the subject: ‘The Essence of the Brontës.’

Muriel Spark also spoke on the subject in a 1961 BBC interview, recorded in Haworth, as she paid special tribute to the effect that Emily Brontë had on her writing and her life. She said that: ‘I was fascinated by her creative mind because it was so entirely alien to my own.’

The Brontës and their world seemed alien to Muriel Spark in 1961, so how much more alien can they seem to us over half a century later? That’s part of their fascination, we want to know the everyday details of their lives – how they dressed, what they read, what they ate. A fellow Brontë lover that I met in Glasgow brought this particular question up this week, so today I will take a look at what constituted the Brontë diet.

This has been a subject of some controversy, because the earliest Brontë biography gave a less than truthful appraisal of their daily meals. Elizabeth Gaskell, in her brilliant but occasionally flawed biography of Charlotte, carried a report from ‘ a good old woman’ who nursed Maria Brontë in her final illness, that: ‘I used to think them spiritless, they were so different to any children I had ever seen. In part I set it down to a fancy Mr. Brontë had of not letting them have flesh-meat to eat… he thought that children should be brought up simply and hardily: so they had nothing but potatoes for their dinner; but they never seemed to wish for anything else.’

Unfortunately Elizabeth had misread the veracity of her witness, as the woman in question, Martha Wright, was less than trustworthy when it came to her opinions of Patrick Brontë. She had been dismissed from his service shortly after his sister-in-law Elizabeth Branwell arrived at the parsonage, with the woman who would become known as Aunt Branwell taking over the duty of nursing the dying Maria. This seems to have tainted her views of the Brontës, and her assertion about their diet is provably untrue.

Emily and Anne Brontë, inseparable friends as well as sisters, came into the habit of writing diary papers together. In the diary paper of 24th November 1834, the earliest we have, the sisters paint a picture of domestic life in the Parsonage on that day. Emily writes (with the haphazard spelling then so typical of her): ‘we are going to have for Dinner Boiled Beef Turnips, potato’s and applepudding the kitchin is in a very untidy state’. She also says that she is peeling apples, and that family servant Tabby Aykroyd later makes her peel potatoes, as Charlotte is making an apple pudding: ‘Charlotte said that she made puddings perfectly and was of a quick but limted intellect.’

We can guess that Charlotte was talking about Tabby here, rather than making such a judgement about herself. This reveals a very tasty meal being prepared, a far cry from the spartan dining suggested by Martha Wright.

Charlotte was not particularly skilled at cooking or baking. In August 1846 she was lodging temporarily in Manchester with her father, as he recovered from cataract surgery – surgery that was undertaken upon him without any anaesthetic, and that he reported didn’t hurt other than a slight burning sensation as the cataracts were cut away. On 21st August of that year she wrote to her great friend Ellen Nussey to say that one of her greatest difficulties was that she ‘was somewhat puzzled in managing about provisions.’

Emily, on the other hand, turned out to be a master of the domestic scene. As Tabby became older and infirm, as the result of a slip on the icy Haworth street that broke her leg and left her with a permanent limp, Emily took over many of the cooking and baking duties that Tabby had formerly held. It was a task that she loved, and like much that she turned her hand to, from piano playing to novel writing, she possessed a brilliance at it. Emily became famed for the quality of the bread that she made, and people said that it was the best in the village. Haworth stationer John Greenwood, who knew the family well, said that Emily could often be found: ‘in the kitchen baking bread at which she had such a dainty hand.’

We also hear of Emily learning German from a book propped up on the table where she was kneading and preparing the day’s loaves.

Bread was the cornerstone of the Brontë diet, and of the diet of early Victorian society in general, but was we’ve seen they also enjoyed potatoes and other vegetables, and beef and mutton, this was sheep farming country after all, would also have been regularly eaten. Pigeon pie was a delicacy to be savoured, and we also know that Emily made bannock, a traditional variety of flatbread. Fish dishes on a Friday would have been a reminder of their Irish heritage, but what else did they eat? A 1981 book called ‘Haworth Kitchen: Recipes From the Home of the Brontës’ reveals a varied and often appealing diet, so whilst many of their meals may of course seem a little jaded to our modern tastes, we can be sure that the Brontës enjoyed nutritious meals that were tasty as well. It was the fuel that powered their imaginations and creative genius, and we can all, from Muriel Spark to myself in my South Yorkshire study, be thankful of that.