At last warmer mornings and sunnier days have arrived; nature’s colours are springing forth in abundance and bees begin their lazy dance from flower to flower. It seems that Easter has timed her entrance perfectly this year, and on this most traditional of celebrations (if we ignore a chocolate egg or four) it’s easy to imagine how the Brontë family must have enjoyed their paschal celebrations two centuries earlier. In today’s new post we’re going to look at Easter and the Brontës.

As we looked at in last year’s Easter post, the Brontë sisters wrote many poems perfect for this time of year, but they also featured Easter in their books too, revealing the impact it had on their lives. Here are some of those occasions:

Jane Eyre

‘“You said it was not likely they should think of being married,” said I, “but you see Mr. Rochester evidently prefers her to any of the other ladies.”

“Yes, I daresay: no doubt he admires her.”

“And she him,” I added; “look how she leans her head towards him as if she were conversing confidentially; I wish I could see her face; I have never had a glimpse of it yet.”

“You will see her this evening,” answered Mrs. Fairfax. “I happened to remark to Mr. Rochester how much Adèle wished to be introduced to the ladies, and he said: ‘Oh! let her come into the drawing-room after dinner; and request Miss Eyre to accompany her.’”

“Yes; he said that from mere politeness: I need not go, I am sure,” I answered.

“Well, I observed to him that as you were unused to company, I did not think you would like appearing before so gay a party—all strangers; and he replied, in his quick way—‘Nonsense! If she objects, tell her it is my particular wish; and if she resists, say I shall come and fetch her in case of contumacy.’”

“I will not give him that trouble,” I answered. “I will go, if no better may be; but I don’t like it. Shall you be there, Mrs. Fairfax?”

“No; I pleaded off, and he admitted my plea. I’ll tell you how to manage so as to avoid the embarrassment of making a formal entrance, which is the most disagreeable part of the business. You must go into the drawing-room while it is empty, before the ladies leave the dinner-table; choose your seat in any quiet nook you like; you need not stay long after the gentlemen come in, unless you please: just let Mr. Rochester see you are there and then slip away—nobody will notice you.”

“Will these people remain long, do you think?”

“Perhaps two or three weeks, certainly not more. After the Easter recess, Sir George Lynn, who was lately elected member for Millcote, will have to go up to town and take his seat; I daresay Mr. Rochester will accompany him: it surprises me that he has already made so protracted a stay at Thornfield.”

It was with some trepidation that I perceived the hour approach when I was to repair with my charge to the drawing-room. Adèle had been in a state of ecstasy all day, after hearing she was to be presented to the ladies in the evening; and it was not till Sophie commenced the operation of dressing her that she sobered down. Then the importance of the process quickly steadied her, and by the time she had her curls arranged in well-smoothed, drooping clusters, her pink satin frock put on, her long sash tied, and her lace mittens adjusted, she looked as grave as any judge. No need to warn her not to disarrange her attire: when she was dressed, she sat demurely down in her little chair, taking care previously to lift up the satin skirt for fear she should crease it, and assured me she would not stir thence till I was ready. This I quickly was: my best dress (the silver-grey one, purchased for Miss Temple’s wedding, and never worn since) was soon put on; my hair was soon smoothed; my sole ornament, the pearl brooch, soon assumed. We descended.’

Easter at Thornfield Hall is the occasion for a grand ball, one where Rochester and Miss Ingram will court each other. We can already feel the despair this brings in Jane’s questioning, little can she dare dream that she will triumph over this society beauty.

Wuthering Heights

‘On Easter Monday, Joseph went to Gimmerton fair with some cattle; and, in the afternoon, I was busy getting up linen in the kitchen. Earnshaw sat, morose as usual, at the chimney corner, and my little mistress was beguiling an idle hour with drawing pictures on the window-panes, varying her amusement by smothered bursts of songs, and whispered ejaculations, and quick glances of annoyance and impatience in the direction of her cousin, who steadfastly smoked, and looked into the grate. At a notice that I could do with her no longer intercepting my light, she removed to the hearthstone. I bestowed little attention on her proceedings, but, presently, I heard her begin—“I’ve found out, Hareton, that I want—that I’m glad—that I should like you to be my cousin now, if you had not grown so cross to me, and so rough.”

Hareton returned no answer.

“Hareton, Hareton, Hareton! do you hear?” she continued.

“Get off wi’ ye!” he growled, with uncompromising gruffness.

“Let me take that pipe,” she said, cautiously advancing her hand and abstracting it from his mouth.

Before he could attempt to recover it, it was broken, and behind the fire. He swore at her and seized another.

“Stop,” she cried, “you must listen to me first; and I can’t speak while those clouds are floating in my face.”

“Will you go to the devil!” he exclaimed, ferociously, “and let me be!”

“No,” she persisted, “I won’t: I can’t tell what to do to make you talk to me; and you are determined not to understand. When I call you stupid, I don’t mean anything: I don’t mean that I despise you. Come, you shall take notice of me, Hareton: you are my cousin, and you shall own me.”

“I shall have naught to do wi’ you and your mucky pride, and your damned mocking tricks!” he answered. “I’ll go to hell, body and soul, before I look sideways after you again. Side out o’ t’ gate, now, this minute!”

Catherine frowned, and retreated to the window-seat chewing her lip, and endeavouring, by humming an eccentric tune, to conceal a growing tendency to sob.

“You should be friends with your cousin, Mr. Hareton,” I interrupted, “since she repents of her sauciness. It would do you a great deal of good: it would make you another man to have her for a companion.”

“A companion!” he cried; “when she hates me, and does not think me fit to wipe her shoon! Nay, if it made me a king, I’d not be scorned for seeking her good-will any more.”’

Hareton and Catherine are both still clearly under the influence of their far from benign upbringings. Heathcliff, in his endless generational quest for revenge, has turned them against each other, but just like the spring flowers that reappear year after year there is no stopping fate, and by the following Easter their love will blossom and their lives will change.

Agnes Grey

‘“Agnes, this sea air and change of scene do you no good, I think: I never saw you look so wretched. It must be that you sit too much, and allow the cares of the schoolroom to worry you. You must learn to take things easy, and to be more active and cheerful; you must take exercise whenever you can get it, and leave the most tiresome duties to me: they will only serve to exercise my patience, and, perhaps, try my temper a little.”

So said my mother, as we sat at work one morning during the Easter holidays. I assured her that my employments were not at all oppressive; that I was well; or, if there was anything amiss, it would be gone as soon as the trying months of spring were over: when summer came I should be as strong and hearty as she could wish to see me: but inwardly her observation startled me. I knew my strength was declining, my appetite had failed, and I was grown listless and desponding; – and if, indeed, he could never care for me, and I could never see him more – if I was forbidden to minister to his happiness – forbidden, for ever, to taste the joys of love, to bless, and to be blessed – then, life must be a burden, and if my heavenly Father would call me away, I should be glad to rest. But it would not do to die and leave my mother. Selfish, unworthy daughter, to forget her for a moment! Was not her happiness committed in a great measure to my charge? – and the welfare of our young pupils too? Should I shrink from the work that God had set before me, because it was not fitted to my taste? Did not He know best what I should do, and where I ought to labour? – and should I long to quit His service before I had finished my task, and expect to enter into His rest without having laboured to earn it? “No; by His help I will arise and address myself diligently to my appointed duty. If happiness in this world is not for me, I will endeavour to promote the welfare of those around me, and my reward shall be hereafter.” So said I in my heart; and from that hour I only permitted my thoughts to wander to Edward Weston – or at least to dwell upon him now and then -as a treat for rare occasions: and, whether it was really the approach of summer or the effect of these good resolutions, or the lapse of time, or all together, tranquillity of mind was soon restored; and bodily health and vigour began likewise, slowly, but surely, to return.’

Easter has arrived and the thoughts of Agnes, just like the thoughts of her creator Anne Brontë, are turned to God and His will. Even so, Agnes is despondent at the thought of her lost love Weston – perhaps Anne was still mourning the loss of her love Weightman? Anne could never more see William Weightman, cruelly taken in his prime by cholera, but she would design a different fate for Agnes.

So what do we see from these three depictions of Easter by Charlotte, Emily and Anne Brontë? They not only help to move these magnificent novels on, they also tell us about Brontë celebrations of this holiday. We see Easter as a time for reflection upon God’s will (Agnes Grey), as a time when fairs and markets were held (Wuthering Heights) and as a time when family and friends came together to rejoice and celebrate (Jane Eyre).

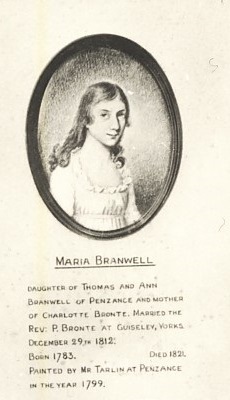

For an all too brief period this time of year held another reason to celebrate for the Brontë family, as just two days ago we passed the 239th anniversary of the birth of Maria Branwell, mother of the Brontës, in Penzance. She was born on 15th April 1783 in Holy Week, just five days before the Easter Sunday of that year and two days after Palm, or Passion, Sunday. Happy birthday Maria, the passion your daughters’ great genius ignites in readers will never be extinguished.

I finish now with my own message urbi et orbi: to the city (village of Haworth) and the world; whatever your religion, faith or creed, the Easter message can be a powerful one for all – at its heart is the triumph of light over darkness, and the unquenchable power of hope. Let’s keep that hope going. If the world or personal circumstances is pressing hard upon you, keep going, keep hope in your heart, and keep reading the novels you love, for lighter days will come again like wheat that springeth green. I hope to see you again next week for another new Brontë post, and I wish you all a very Happy Easter!

I really enjoy these posts on a Sunday. It’s nice to have tea with them. And very informative and interesting.

Truly love your site and thank you for the uplifts…