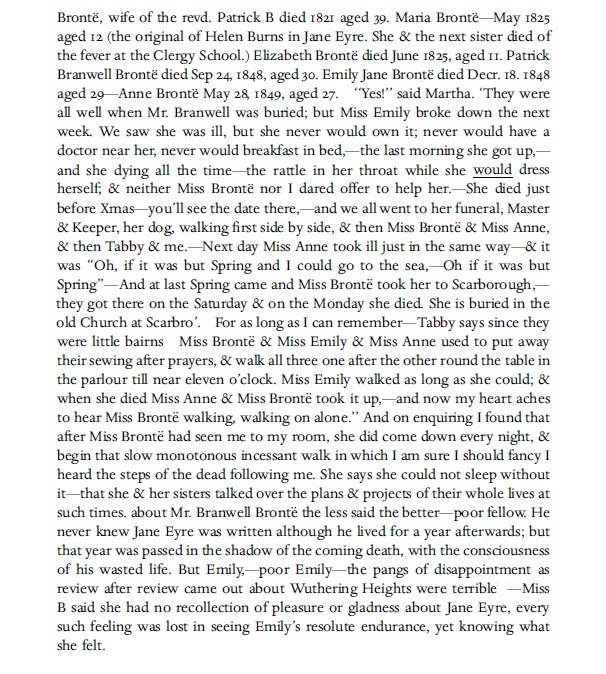

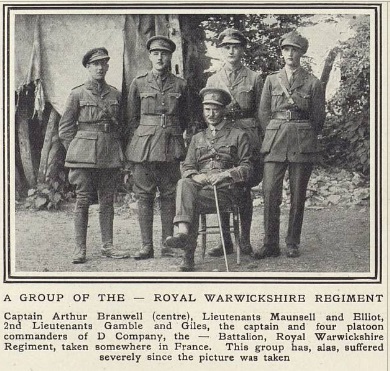

On this Remembrance Sunday let us start by remembering and honouring all those who gave their today for our tomorrows; men like the fellow officers of Captain Arthur Branwell captured in this photograph not far from the French front. This first cousin of the Brontës once removed (his father Thomas Brontë Branwell travelled to Haworth and met his cousin Charlotte Brontë) was the only one of these five officers to make it home alive. There were many other such stories then, and still wars rage around the world stoked up by men who are safe in the knowledge that there will never be a front line that they themselves will serve at.

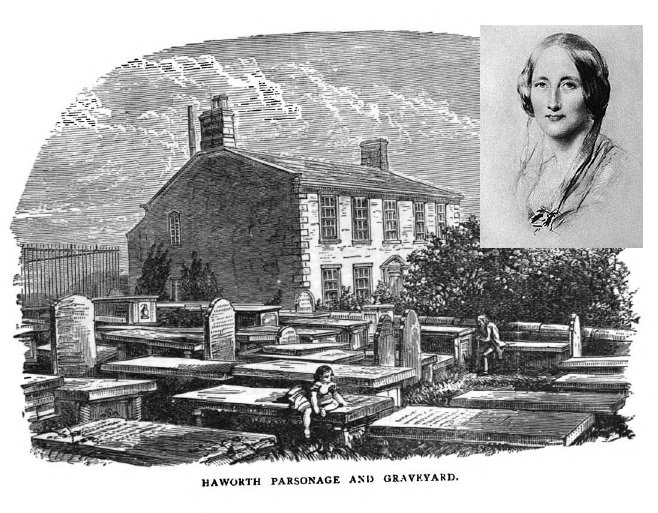

We also remember a writer who became a great friend of Charlotte Brontë and the great chronicler of her: Elizabeth Gaskell whose anniversary is this week; she died aged 55 on 12th November 1865. Elizabeth never met Anne Brontë, and so most of her pronouncements on Anne within her biography of Charlotte are based upon conversations with Charlotte and others. Nevertheless, her The Life Of Charlotte Brontë introduced Anne Brontë to the world as a person and not merely as the name on a book cover. In today’s post we look at the strange circumstances of the death of Elizabeth Gaskell, and at the tributes paid to her at the time.

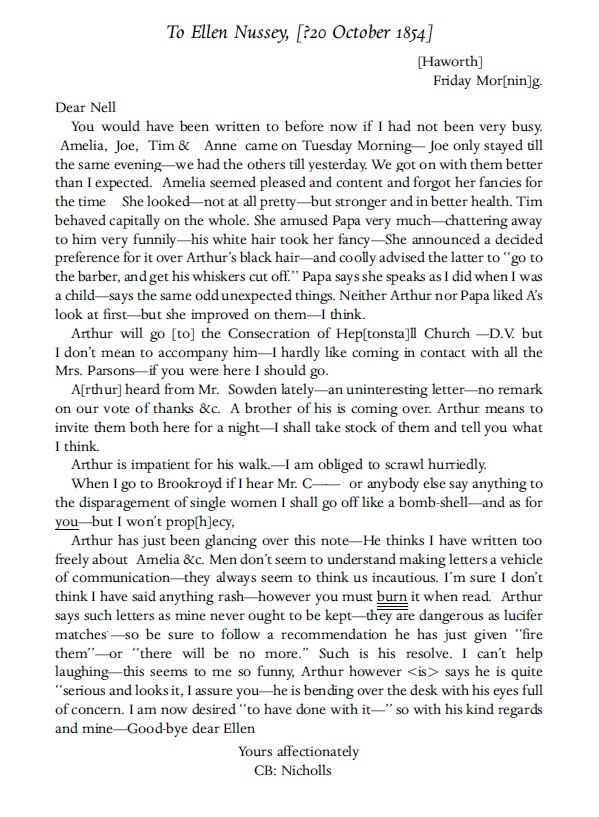

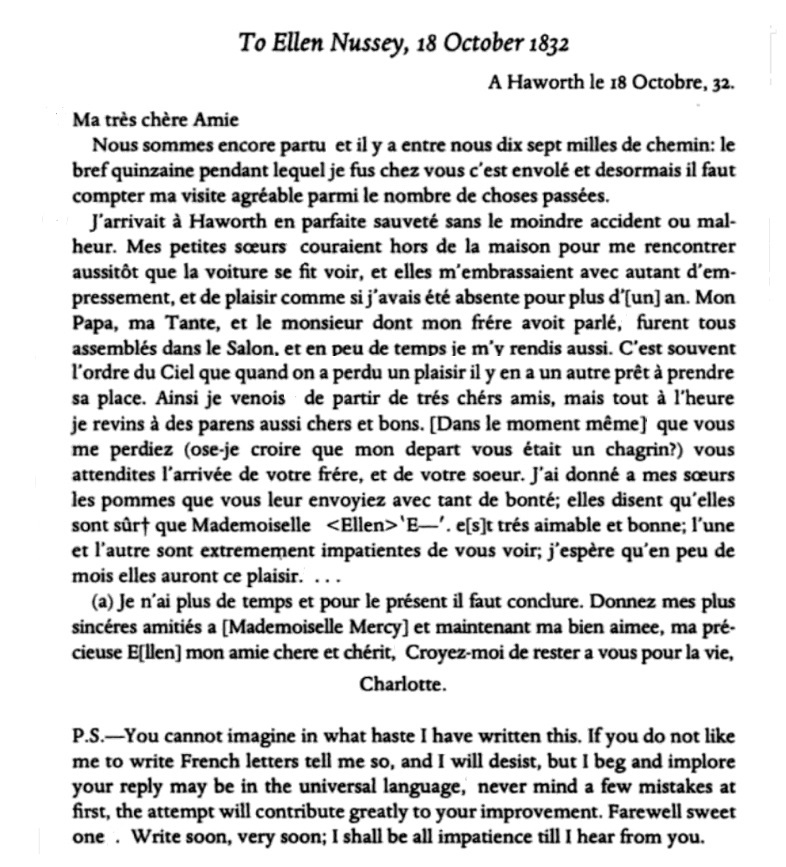

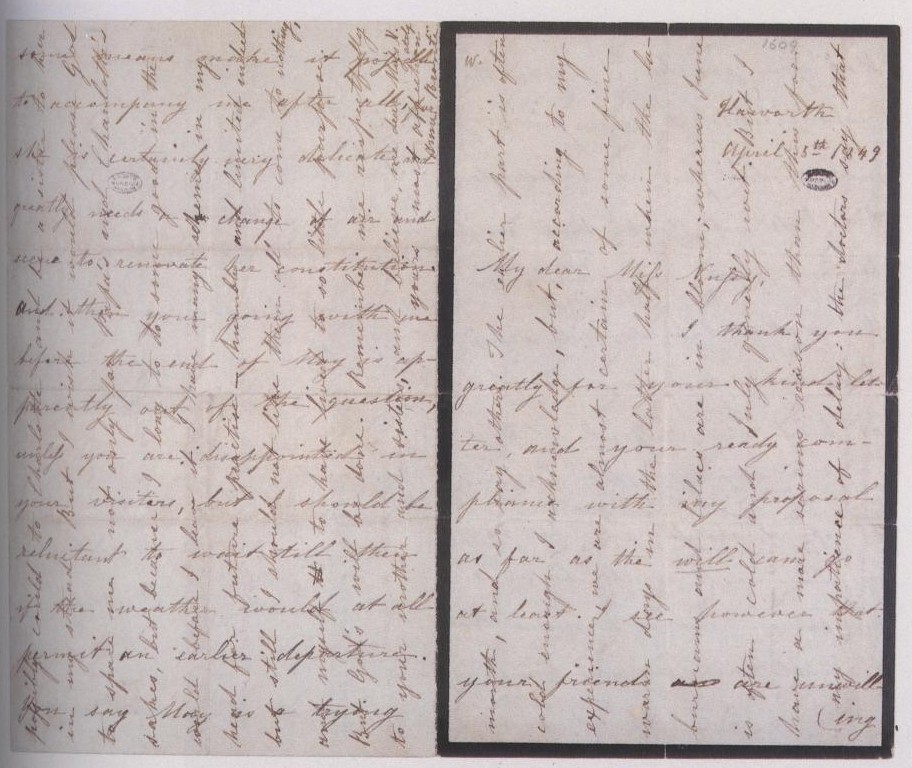

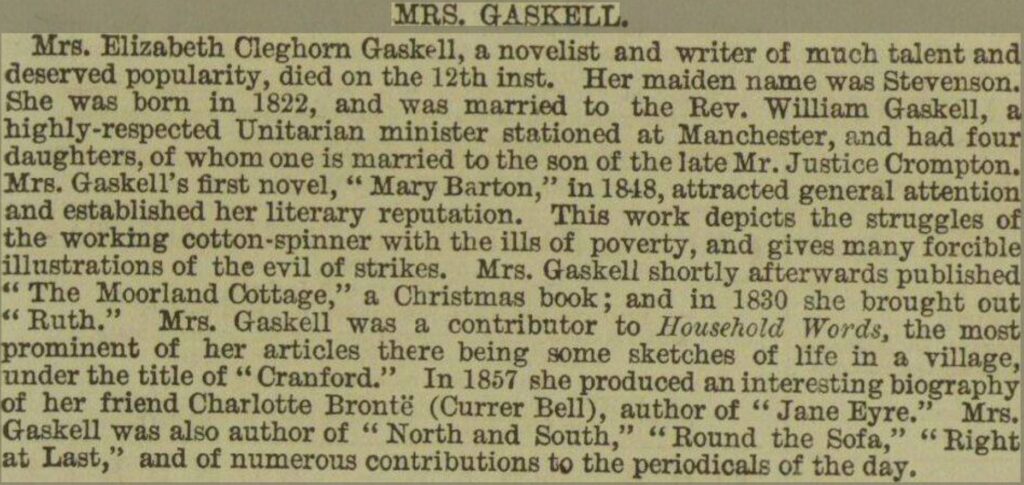

We will be turning to the archives and to the newspapers of the day, before finishing with a very special letter. Firstly, let’s take a look at the simple obituary included in the London Illustrated News of 18th November 1865:

The Bury Times of 18th November 1865 gave the first details of the circumstances of Elizabeth’s death:

“Mrs. Gaskell, the authoress and biographer, was suddenly struck by death on Sunday last, while in the act of reading to her daughters. She has thus passed away in the midst of that domestic life out of which her literary talent grew and flourished. It is not many years ago that it was suggested to her to attempt to divert her mind from a deep household sorrow by the exercise of her imagination in the composition of a work of fiction, and Mary Barton was then written – much of it on backs of letters, and on other scraps of paper that fell in her way, probably with no intention of publication, and certainly with no hope of fame. The book was received with great interest and sympathy by the public, and with some hostility by the chief employers of labour in the Manchester district, who were displeased that their relations with the work-people should be discussed in this fashion, and perhaps not altogether satisfied with the spirit of entire justice with which Mrs. Gaskell treated some burning questions of social economy. From that time Mrs. Gaskell has written continuously and well.”

The deep household sorrow referenced above was the death of Elizabeth’s baby son William in 1844. It was indeed this that provided the catalyst for her first novel Mary Barton: A Tale Of Manchester Life. Elizabeth was mourned particularly in the Manchester and greater Lancashire area, and this next obituary, from the Ulverston Advertiser and General Intelligencer of 16th November 1865 gives a fitting tribute to her life and work:

“On Monday evening, the melancholy intelligence reached Manchester of the death of Mrs. Gaskell, the wife of the respected minister of the Unitarian Chapel, Cross-Street. She was visiting in London, where probably the death of Mr. Justice Crompton (whose son married Miss Gaskell) somewhat prolonged her stay. Her death was very sudden, and that there could have been no expectation of so speedy a termination of her life-work, nor even a thought of danger, is shown by the fact that Mr. Gaskell was preaching in his own chapel on Sunday, and was at home when the news of her decease reached him.

Mrs. Gaskell, whose maiden name was Stevenson, was born about the first year of this century [she was actually born in 1810]. She was brought up by some aunts, named Holland, at Knutsford. It was shortly after Mr. Gaskell’s settlement at Manchester, as co-pastor with the late Mr. Robberds, that the deceased lady met her future husband while she was visiting with Mr. Robberds. Their marriage took place about the year 1832, and four daughters were born to them. Mrs. Gaskell lived the honoured and useful life of a minister’s wife for many years before her name became known as an authoress. Doubtless during all those years she was maturing the powers which enabled her to take so high a place among modern novelists and biographers. With the modesty of doubt in her own gift, she issued her first work, Mary Barton, anonymously in 1848. It attracted great interest from the fact that its scene was laid in this neighbourhood, and that it revealed a new phase of life in a style of novel as it was entertaining.

Since 1848 Mrs. Gaskell has written much, and not many publishing scenes have passed without some work from her pen. Indeed, considering the lateness of the harvest the wonder is that it has been so bountiful. Ruth appeared about 1852: and although not so striking a work as its predecessor, Mrs. Gaskell’s reputation lost nothing by it. Another of the popular novels was North And South, in which the painful incidents of a strike in the manufacturing districts were narrated with great vigour. Besides these Mrs. Gaskell wrote many less elaborate stories for the leading serials, some of which were subsequently published in a collected form.

But her greatest work and that by which she will be longest known, is her Life Of Charlotte Brontë, of which it has been said that no biography has equalled it since Boswell’s “Johnson”. In the earlier editions of this now standard work, some personal references were made which created much discussion, and which were omitted from subsequent editions…

Her conversational powers were of no mean order, and she was at all times an important acquisition to the social circle. Of late years she has travelled much abroad; but her inspiration was always found in English life and character. Her death leaves a blank that will not be easily filled.”

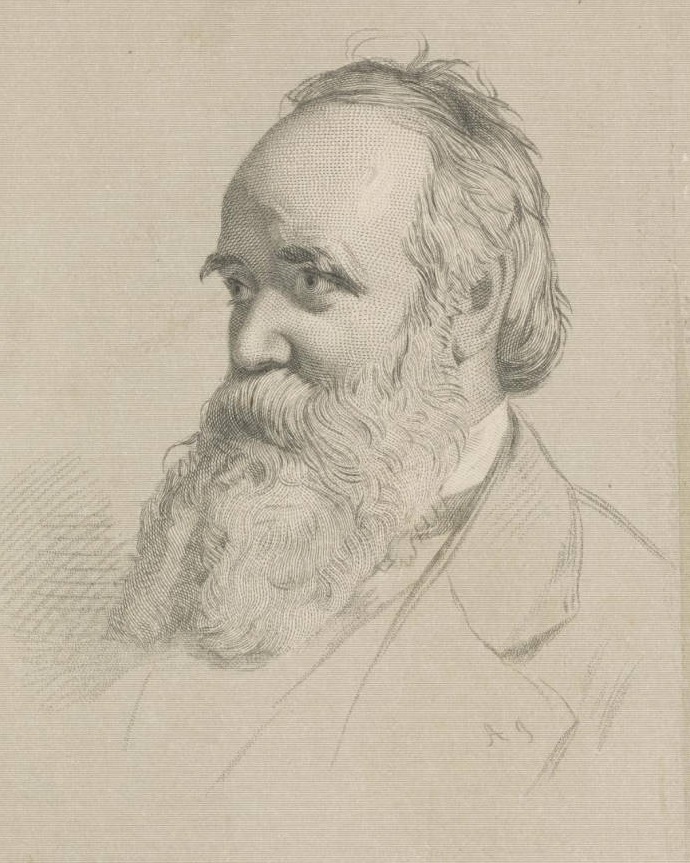

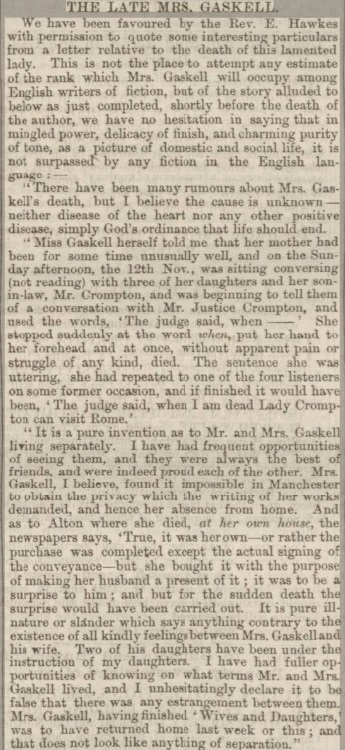

It is interesting to note that in obituaries of the time, Elizabeth Gaskell is most known for her biography of Charlotte Brontë. As reported above, Elizabeth’s husband, Reverend William Gaskell, was not with Elizabeth when she died. This it seems set some tongues wagging, and it was widely believed that Elizabeth and William were in fact separated and living apart at the time of her death. This was refuted by Reverend Hawkes who had known Elizabeth in Hampshire, and his account of her death appeared in the Westmorland Gazette of 25th November 1865:

The fact is that Reverend Gaskell did not even know that his wife had bought this property 190 miles from their Manchester home, still less that she often spent time there. We shall read later, however, that her plan was to eventually persuade her husband to retire there with her.

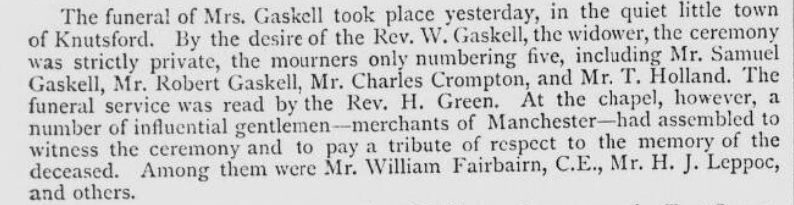

Reverend Hawkes’ report also confirms Elizabeth’s final word: ‘when’. Elizabeth’s body was transported from Hampshire to the Cheshire town of Knutsford for her funeral (her grave is at the head of this post). Although born in London, she had come home to the beautiful town in which she had been raised by her aunts. As this account from the Pall Mall Gazette of 18th November 1865 shows, her funeral was sparsely attended but the merchants of Manchester had gathered to pay tribute – any enmity now seemingly set aside:

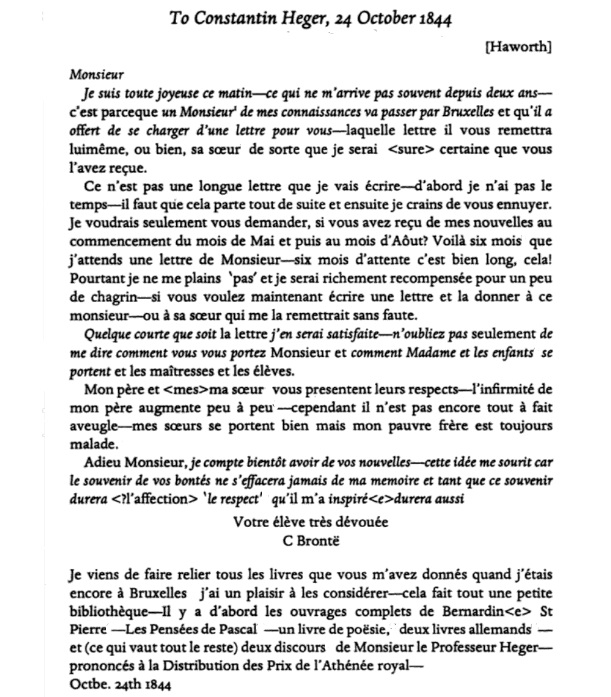

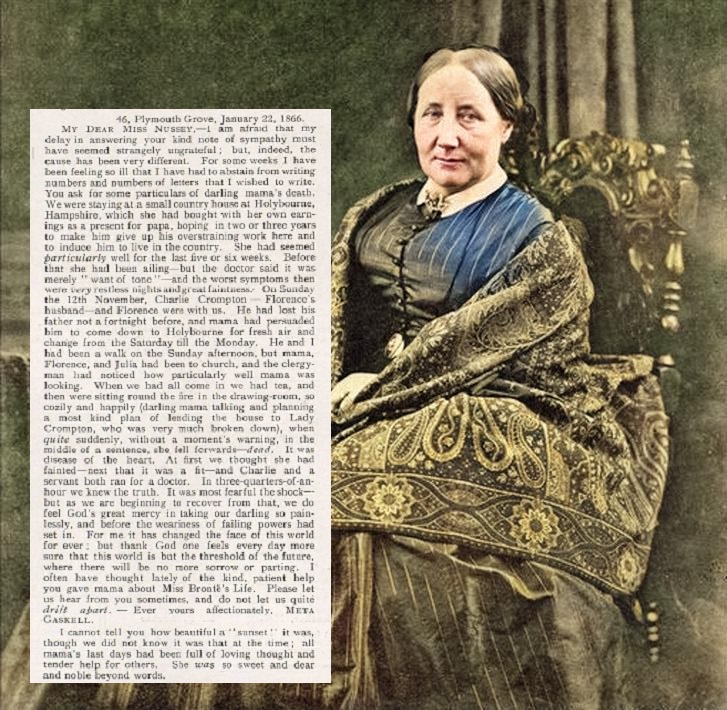

It is sad to note that all in attendance were men, the daughters of Elizabeth Gaskell were not allowed to attend their mother’s funeral. This was a common practise at the time. It is to one of Elizabeth’s daughters that we turn for the final word on her death though. Ellen Nussey, great friend of Charlotte Brontë, came to know Elizabeth Gaskell and her family when she provided assistance with Elizabeth’s biography of Charlotte. After reading of Elizabeth’s passing, Ellen wrote to her daughter Meta Gaskell to express her condolences and ask for more information. The letter that Meta sent to Ellen in January 1866 is beautiful and melancholic:

‘Noble beyond words’ is a fine tribute to Elizabeth Gaskell and to all who we remember today. The Cross-Street chapel in Manchester where William preached last night hosted an event to celebrate the life of Anne Brontë, and I hear from those in attendance that it was a great success. Well done to all who organised it! I hope you can join me again next week for another new Brontë blog post.