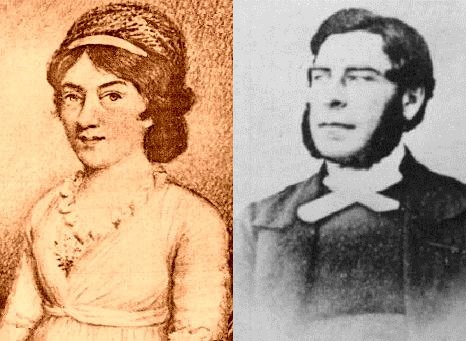

The second of December is an important date in the wider Brontë story for it marks the two most vital life events of two people who were central to the Brontë sisters’ lives, although they happened hundreds of miles from Haworth, and many decades before and after the Brontë sisters were alive. This day marked the birth of Elizabeth Branwell in 1776 and the death of Arthur Bell Nicholls in 1906, so today we’ll take a brief look at them before and after they entered and exited the Brontë story.

Elizabeth Branwell has long been a heroine of mine, which is why I wrote my biography of her, ‘Aunt Branwell and the Brontë Legacy‘. In 1821, Elizabeth Branwell left her comfortable existence in Cornwall to travel 400 miles to Haworth to nurse her dying sister Maria Brontë. After Maria’s death, and possibly after a suitable period of mourning had passed, she could have returned to her beloved Penzance, but she instead chose to stay for 21 years until her own death, and never saw Cornwall again. Without the emotional and financial support that Aunt Branwell provided there can be no doubt that there would be none of the Brontë novels we all love, but what was her life like before she arrived at the draughty moorside parsonage in Haworth?

Elizabeth Branwell was born into one of Penzance’s leading families in 1776, in far more illustrious circumstances than that of Patrick Brontë who was born in Ireland just four months after Elizabeth. Thomas Branwell, her father, was a very successful businessman, and her mother Anne, nee Carne, was also from a leading Penzance family who were banking pioneers. Thomas continued to amass property and businesses throughout his life, and by the time of his death he owned a number of houses across Penzance, as well as the stately Tremenhere House, a number of shops, a warehouse at the quayside, the Golden Lion Inn and even his own brewery (which may be surprising as he was a strict Wesleyan, a cause which avowed temperance).

We can see then that Elizabeth’s childhood, and later that of her younger sister Maria, must have been a comfortable one, unlike that experienced by the vast majority of children growing up in the latter half of the eighteenth century, but even the upper classes, and the rising merchant class, were not immune to the dangers of the time. Elizabeth came from a large family, but many of them died in infancy or childhood. Indeed her given name of Elizabeth had earlier been conferred upon another Elizabeth Branwell, who was born and died in the year 1772.

Only one of Elizabeth’s brothers survived into adulthood, but his story shows how the Branwells had also become influential in the politics of the growing town of Penzance. Benjamin Branwell was a year older than Elizabeth and in 1809, aged 33, he became Mayor of Penzance. Benjamin, like most of the Branwell family, was a staunch supporter of Methodism and there is some speculation, but not proof, that this may have brought him to Yorkshire, where he could have met Patrick Brontë, and even that this could have some bearing on Patrick’s later marriage to Benjamin’s sister Maria.

Too many people think of Aunt Branwell as an unsmiling, austere woman but that seems to be far from the truth. Ellen Nussey, always a trustworthy chronicler of the Brontë family, reported that Elizabeth Branwell loved to regale people with tales of her fun filled and happy past:

‘She talked a great deal of her younger days; the gaieties of her dear native town Penzance, in Cornwall, the soft, warm climate, etc.’

We even get a first hand account of how Elizabeth still loved to laugh and play jokes when she was in Haworth:

‘She gave one the idea that she had been a belle among her home acquaintances. She took snuff out of a very pretty gold snuff-box, which she sometimes presented to you with a little laugh, as if she enjoyed the slight shock and astonishment visible in your countenance.’

We also know how personable and kind Elizabeth Branwell was from a report of her previous sojourn to Yorkshire. You may think that Elizabeth’s arrival in Haworth in 1821 was her first visit to Yorkshire, especially given the long distance she travelled and the perilous nature of such a journey in those days, but in fact she had already spent over a year in Yorkshire six years previously. We know that Elizabeth Branwell was in Thornton, near Bradford, in May 1815, and she may even have assisted Patrick and Maria in their move to Thornton from their previous parish of Hartshead. She stayed in Thornton until returning to Cornwall on 28th July 1816, and whilst there she acted as godmother to Elizabeth Brontë and witnessed the birth of Charlotte Brontë. We know these dates because they feature in the diary of Elizabeth Firth of Thornton, who was also godmother to Elizabeth Brontë and later to Anne Brontë. Miss Firth’s account of Elizabeth Branwell’s departure shows what a kind and tender hearted woman she was:

‘I took leave of Miss Branwell, she kissed me and was much affected. She left Thornton that evening.’

One reason that Elizabeth Branwell was so affected was that she obviously loved the three nieces, Maria, Elizabeth and baby Charlotte, she had come to know in Thornton. It wouldn’t, of course, be the last she would see of them.

So as we say ‘Happy Birthday’ to Elizabeth Branwell, we say a fond farewell to Arthur Bell Nicholls. He died on this day aged 87, meaning that a man who played such a prominent role in the lives of the Brontë sisters, and one of them in particular, lived in to the twentieth century.

Arthur was born on January 6th 1819 in Killead, County Antrim, in what is now Northern Ireland. He arrived in Haworth to serve as assistant curate to Patrick Brontë in May 1845, his first position within the Church of England.

Arthur’s heart was soon captured by his curate’s eldest daughter, Charlotte Brontë of course, but the course of true love certainly didn’t run smooth. After his proposal in December 1852 she let him know in no uncertain terms that she could never love him, although she was moved at the terrors that his proposal brought to him, as she revealed in a letter to Ellen on December 15th:

‘He stopped in the parsonage: he tapped: like lightning it flashed on me what was coming. He entered – he stood before me. What his words were – you can guess; his manner you can hardly realize – nor can I ever forget it. Shaking from head to foot, looking deadly pale, speaking low, vehemently yet with difficulty – he made me feel what it costs a man to declare affection where he doubts response… The poignant pity inspired by his state on Monday evening – by the hurried revelation of his sufferings for many months, is something galling and irksome. That he cared something for me, and wanted me to care for him, I have long suspected – but I did not know the degree or strength of his feelings.’

With a firm refusal given, Arthur prepared to leave Haworth and become a missionary in Australia. On his last service in St. Michael’s and All Angels church he stood shaking in the pulpit unable to speak, and had to be led out of the church by some of the congregation whilst many of those in the pews sat there weeping. Charlotte later wrote that:

‘I found him leaning against the garden-door in a paroxysm of anguish – sobbing as women never sob.’

Charlotte still insisted that she had no feelings for him, although in January 1853 she confessed to Ellen that:

‘I am sorry for one other person whom nobody pities but me. Martha is bitter against him: John Brown says he should like to shoot him. They don’t understand the nature of his feelings… Dear Nell, without loving him I don’t like to think of him, suffering in solitude, and wish him anywhere so that he were happier.’

Arthur left Haworth, but not for Australia, and over time he and Charlotte started a correspondence that eventually led to his triumphant return to Haworth and his marriage to Charlotte in June 1854. Charlotte was surprised, and delighted, to find that she loved her new husband, but it was not to be a long happiness as she died whilst pregnant in March 1855. The widowed Arthur was distraught, but what happened to him after Charlotte’s death?

Arthur remained loyal to the Brontë family, continuing to walk Emily’s dog Keeper, and he also continued to live at the Parsonage serve as Patrick Brontë’s assistant curate. In reality, Arthur was really the curate himself, taking nearly all the services owing to Patrick’s age and eyesight, which was once again failing.

After Patrick’s death in June 1861 Arthur must have expected that he would be given the role he had already been carrying out for many years as Curate of Haworth, but for some inexplicable reason it was not to be and the post was instead awarded to Reverend John Wade, a man who had little time for his illustrious predecessor nor his family.

Arthur was devastated once more, and with nothing but sad memories left to him in Haworth he gave up the priesthood altogether and returned to Ireland where he worked as a farmer. He stayed with his aunt in Banagher, County Offaly, the wife of a Reverend Allan Bell. In 1864 he married his aunt’s daughter, his cousin Mary Anna Bell. It is perhaps somewhat unusual that Arthur first married a woman who had written under the pseudonym of Currer Bell and later married a woman who was the daughter of Curate Bell.

Athur lived out his remaining decades in a peace, of sorts, although he was often the target of Brontë souvenir hunters. He refused to deal with them all, until in later life, just like Ellen Nussey, he was conned out of much of his Brontë letters and artifacts by Clement Shorter. Arthur had loved Charlotte deeply, and he never forgot the Brontës or Haworth. The family servant Martha Brown often visited Arthur in Ireland, and may have worked for him there, showing that a friendship had replaced the animosity that once existed between them.

On this day then, let us remember both Elizabeth Branwell and Arthur Bell Nicholls. Without them, the Brontë story would have been very different.

A nice warm tribute to Arthur Nick. I had completely overlooked the day.

Thanks Stephen,and of course your book about Arthur, ‘The Last Bronte’, is an excellent read.

Excellent background. I wonder why Elizabeth had such a modest amount to bequeath to her nieces if her father was so well off.

Also, would a Brontë trip to Penzance be interesting? Thanks. Mel

Thank you for this interesting post. Has anyone written a biography of the Branwell family? Angela Crow did a lot of research but I don’t think that it got into print.

Funny you should say that Catherine… my book ‘Aunt Branwell and the Bronte Legacy’ which came out earlier this year has a lot of information on the wider Branwell family, including their descendants living today! (Wish I’d have known of Angela Crow’s research, it would have been nice to compare research points with her).

Thank you for all your research and sharing it. So much of history is lost forever by those who take little interest in it, but it repeats itself which is invaluable in going forward. Again, thank you.