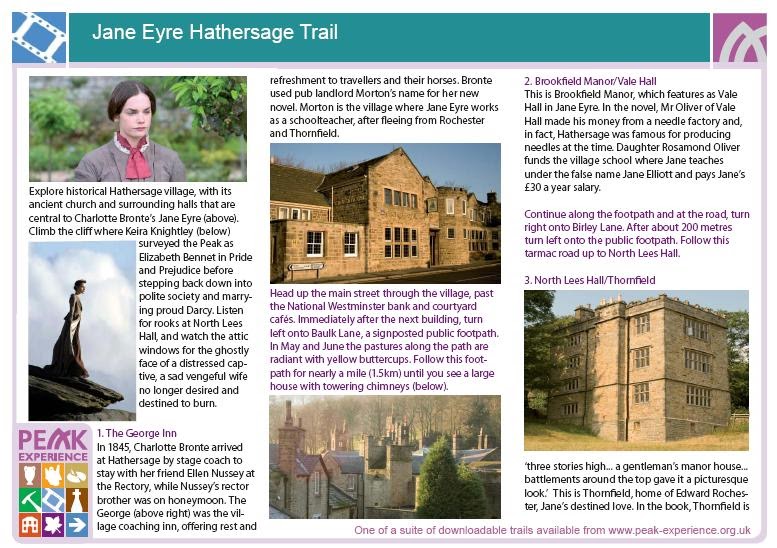

On a certain day last month I felt in need of reflection and a recharging of my spirit’s batteries – and so I travelled to somewhere absolutely perfect for it, Kirkstall Abbey on the outskirts of Leeds. It’s an incredibly beautiful building (so warning – this is a picture heavy post, my phone camera was in high demand,) a ruin but a magnificent ruin and on that day I’ve never felt an atmosphere like it in any other building I’ve ever been in. Perhaps that was because I was acutely aware that the day I was there saw a very important event in the Brontë story take place exactly 206 years earlier.

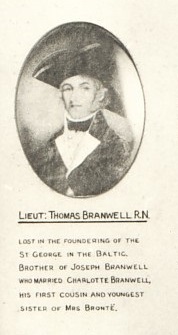

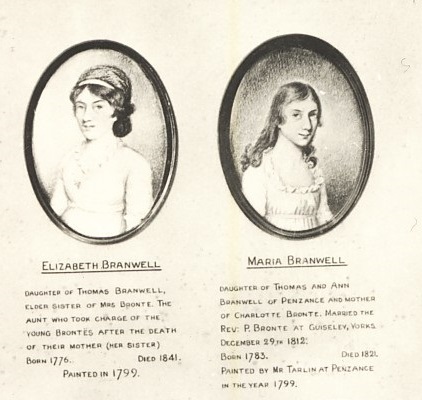

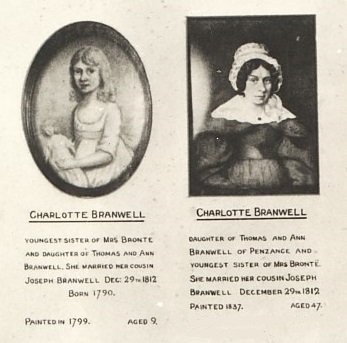

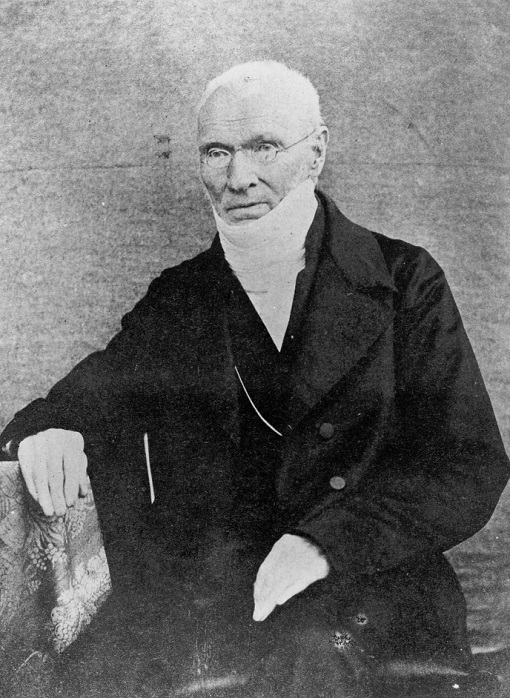

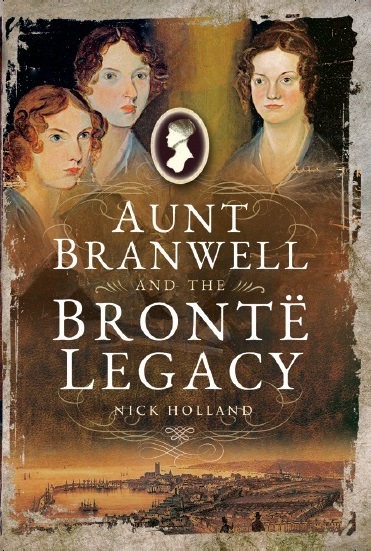

Kirkstall Abbey was the very spot on which Patrick Brontë proposed to Maria Branwell. A series of strange events had brought them to that day in October 1812, and things could have been very different for them. Maria was then in her late 20s and Patrick in his mid 30s, perhaps beyond the first flush of youth but still searching for love – they met in the summer of 1812 and within six months they were married, leading to the family of six children that we all know and love: Maria Brontë, Elizabeth Brontë, Charlotte Brontë, Patrick Branwell Brontë, Emily Jane Brontë, Anne Brontë.

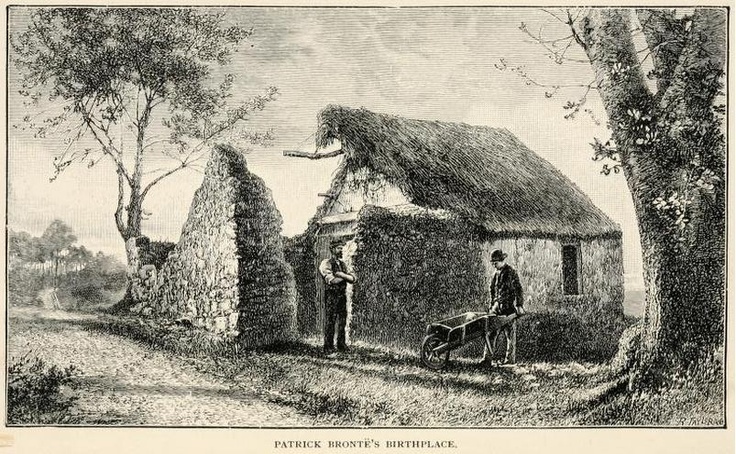

They could have met others and married earlier. If as a child Patrick had not been spotted reading ‘Paradise Lost’ aloud by County Down vicar Andrew Harshaw he would not have been awarded a place in school, he would not have become a teenage teacher, he would not have been given a scholarship to Cambridge, he would not have served as an assistant curate in Shropshire and would not have met local teacher John Fennell there, he would not have moved to Yorkshire to become a priest in Dewsbury and then Hartshead. By coincidence he would not have found that his Shropshire friends the Fennells had also moved to Yorkshire and opened a school in nearby Woodhouse Grove, near Leeds, and they would not have heard of his arrival and invited him to examine the children in classics there. By another coincidence the Fennel’s niece Maria Branwell had that summer made an arduous journey to Yorkshire from Cornwall to Woodhouse Grove to act as an assistant at the school. They would never have met, never felt their souls connect, never have married and had the Brontë children. So many coincidences, but in life are there really any coincidences?

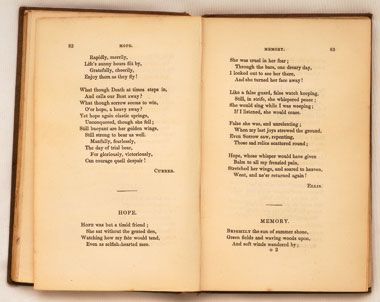

It was these circumstances, this chain that could have had an impediment at any time which would have irrevocably have changed literary history, that led Patrick to take to his knee in the magnificent grounds of Kirkstall Abbey and ask Maria Branwell to be his wife. Although they had known each other less than a handful of months, thankfully she had no hesitation in accepting. They married in December 1812, and a year later Patrick published his collection of poetry ‘The Rural Minstrel‘ within which was a tribute to the place they had cemented their love. His poem ‘Kirkstall Abbey’ is long, but here’s an extract:

“’Hail ruined tower! That like a learned sage,

With lofty brow, looks thoughtful on the night;

The sable ebony, and silver white,

Thy ragged sides from age to age,

With charming art inlays,

When Luna’s lovely rays,

Fall trembling on the night,

And round the smiling landscape, throw,

And on the ruined walls below,

Their mild uncertain light.

How heavenly fair, the arches ivy-crowned,

Look forth on all around!

Enchant the heart, and charm the sight,

And give the soul serene delight!

Whilst, here and there,

The shapeless openings spread a solemn gloom,

Recall the thoughtful mind, down to the silent tomb,

And bid us for another world prepare.

Who would be solemn, and not sad,

Who would be cheerful, and not glad,

Who would have all his heart’s desire,

And yet feel as his soul on fire,

To gain the realms of his eternal rest,

Who would be happy, yet not truly blest,

Who in the world, would yet forget his worldly care,

With hope fast anchored in the sands above,

And heart attuned by sacred love,

Let him by moonlight pale, to this sweet scene repair.”

It was to the sweet scene of Kirkstall Abbey, perhaps by the softly flowing brook alongside it, that Patrick and Maria repaired, doubly blessed with hearts attuned by sacred love. Doubtless as they grew older the Brontë children were told of the importance of Kirkstall Abbey to the Brontë story, for we know that Charlotte Brontë visited it and indeed sketched it herself.

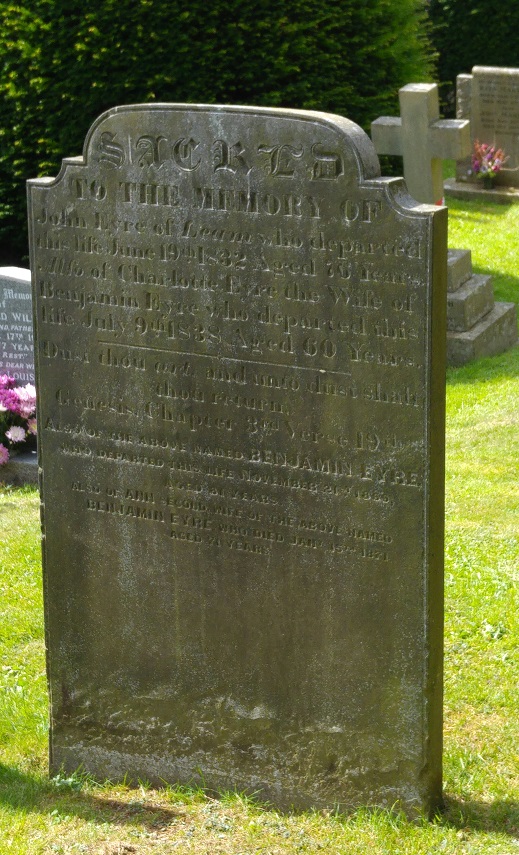

So, it is accepted that Kirkstall Abbey marked the spot where Patrick proposed to Maria, but the date is unknown. Or is it? I travelled to Kirkstall Abbey on 23rd October, and I believe this is the date that Patrick and Maria pledged their love to one another in the abbey grounds and agreed to marry. I think the clue to this can be found in Maria Branwell’s letter to Patrick dated 24th October 1812:

‘Unless my love for you were very great how could I so contentedly give up my home and all my friends?… Yet these have lost their weight… the anticipation of sharing with you all the pleasures and pains, the cares and anxieties of life, of contributing to your comfort and becoming the companion of your pilgrimage, is more delightful to me than any other prospect which this world can possibly present.’

This, to me, is clearly the letter of a woman writing to her new fiance on the day after they became engaged, and now looking ahead to their married life together. A happy letter, full of love, and indeed I found Kirkstall Abbey today to be a magnificent building full of peace and an atmosphere of love. The Abbey itself doesn’t mark its place in the Brontë story, alas, but in the Kirkstall Abbey shop I found that Emily Brontë was present there after all – another coincidence?