The day of love is here, so in today’s special post we’re heading back exactly 184 years to the day when love arrived at Haworth Parsonage interspersed with a selection of Victorian-era Valentine’s Day cards!

The giving of Valentine’s cards far predates the giving of Christmas cards that only became popular in the second half of the nineteenth century. The Brontë sisters received their first cards on February 14th, 1840, and even though they eventually discovered the source was their father’s new assistant curate it must still have been a thrill for them – especially for 20 year old Anne.

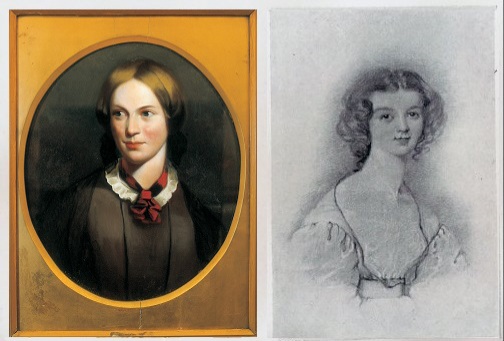

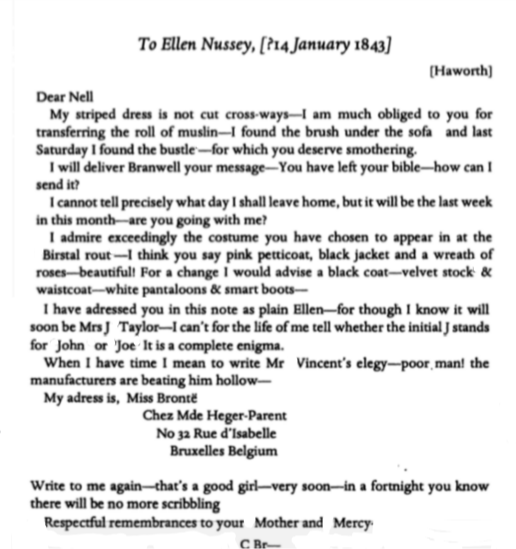

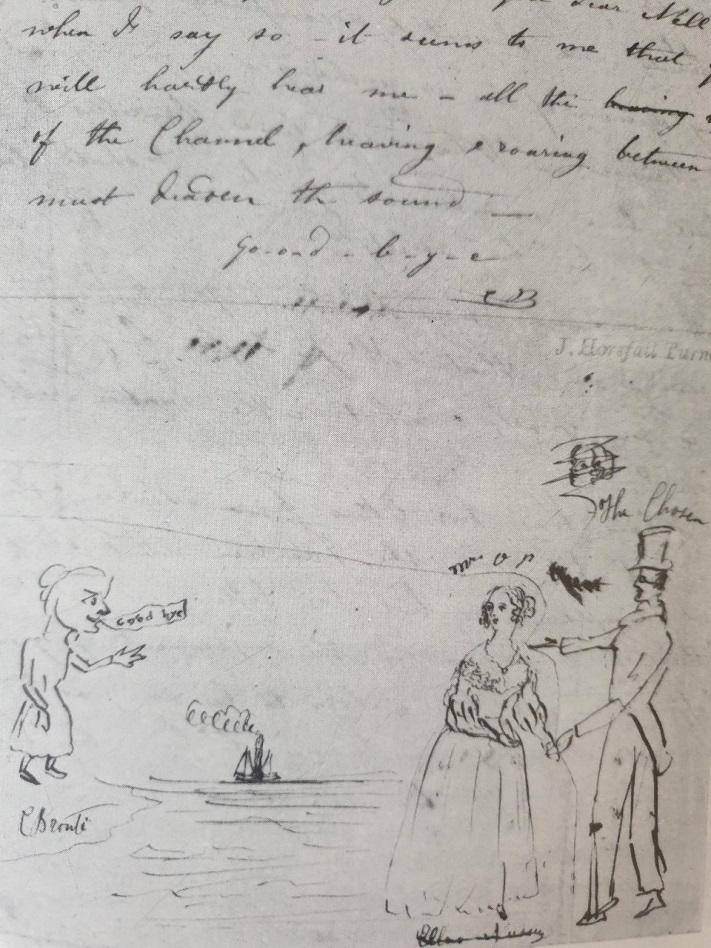

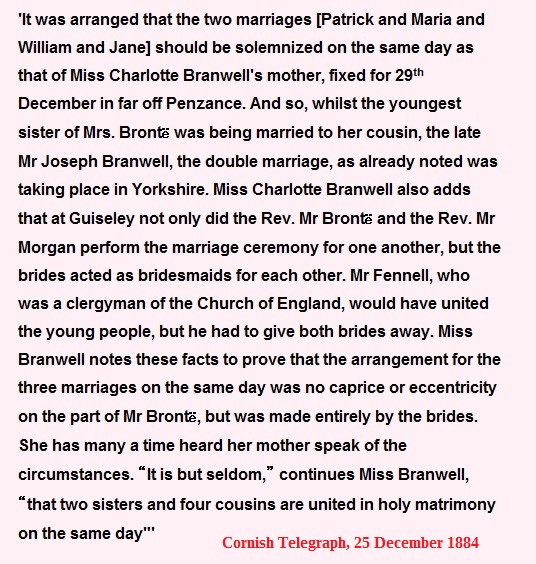

The man was, of course, William Weightman, who had recently gained his Master of Arts degree from the newly founded Durham University and commenced life in the clergy. In the run up to February 14th he was astonished to find out that none of the sisters had ever received a Valentine’s day card, and characteristically he sprung into action. What he did next was a testament to his kind and good nature, although as we shall see Charlotte later took a different view of it. He not only bought four cards, not wanting the visiting Ellen Nussey to feel left out, but wrote personalised verses in each. His efforts didn’t end there, as he then walked more than ten miles across very rugged terrain in the height of winter to Bradford, where he posted them. He did this of course so the Brontë sisters wouldn’t guess he had sent them because of a local postmark, thereby adding to the excitement and intrigue.

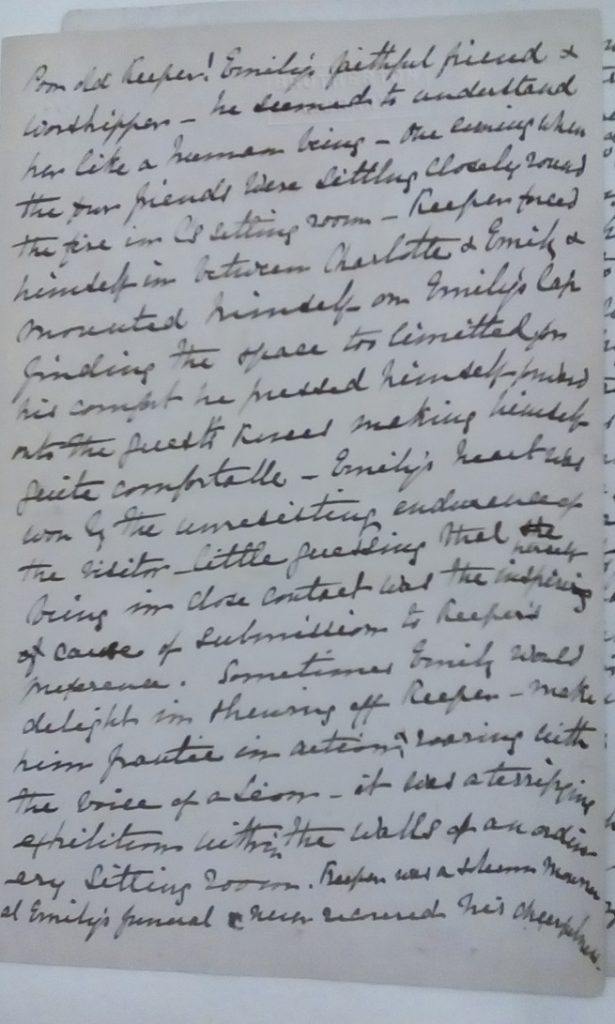

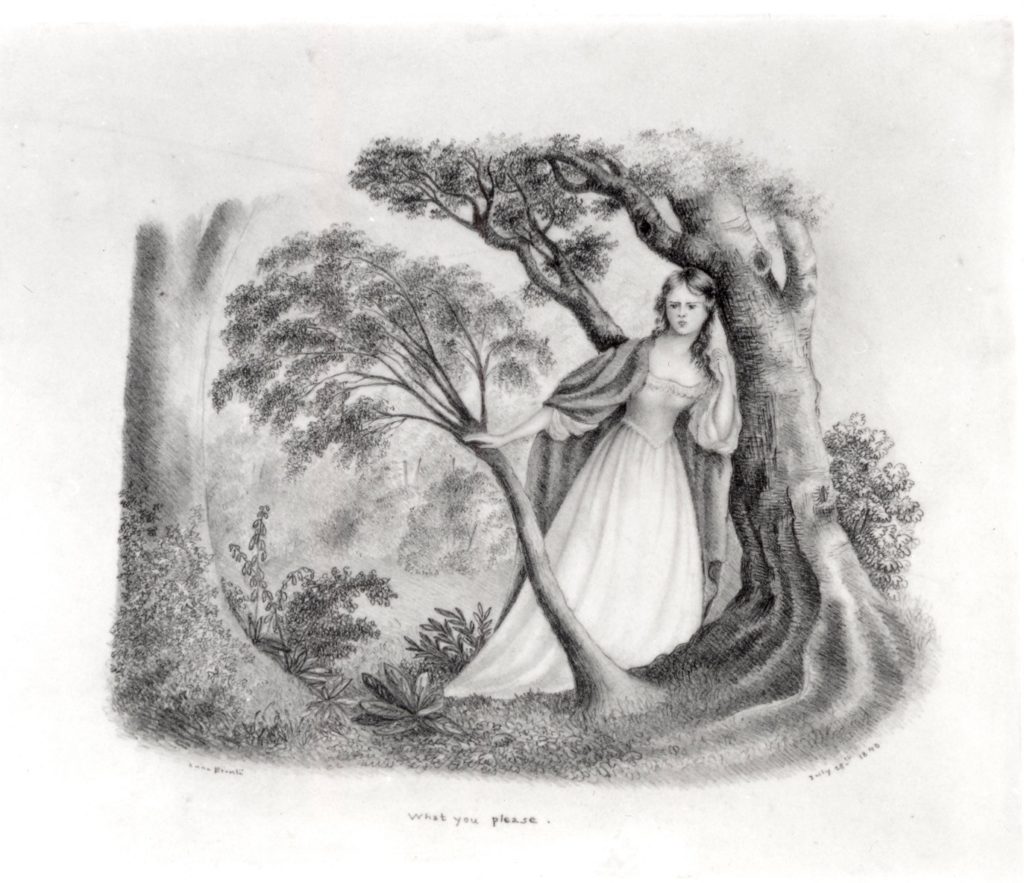

The titles of the poems on each card can be equally intriguing to us: with only one can we positively identify the target, as ‘Fair Ellen, Fair Ellen’ was obviously meant for the great Brontë friend Miss Nussey. One title, sadly, has been lost in the intervening years, but two of the other three were called ‘Soul Divine’ and ‘Away Fond Love’. Could ‘Soul Divine’ have been for Emily, in tribute to her indomitable spirit, and could ‘Away Fond Love’ have been a reference to Anne, who was at that moment looking for a new situation as a governess that would take her away from Haworth? If so, then the missing title could have been for Charlotte, who may possibly have ripped it up in a fit of pique after falling spectacularly out with the young man she had once thought so highly of.

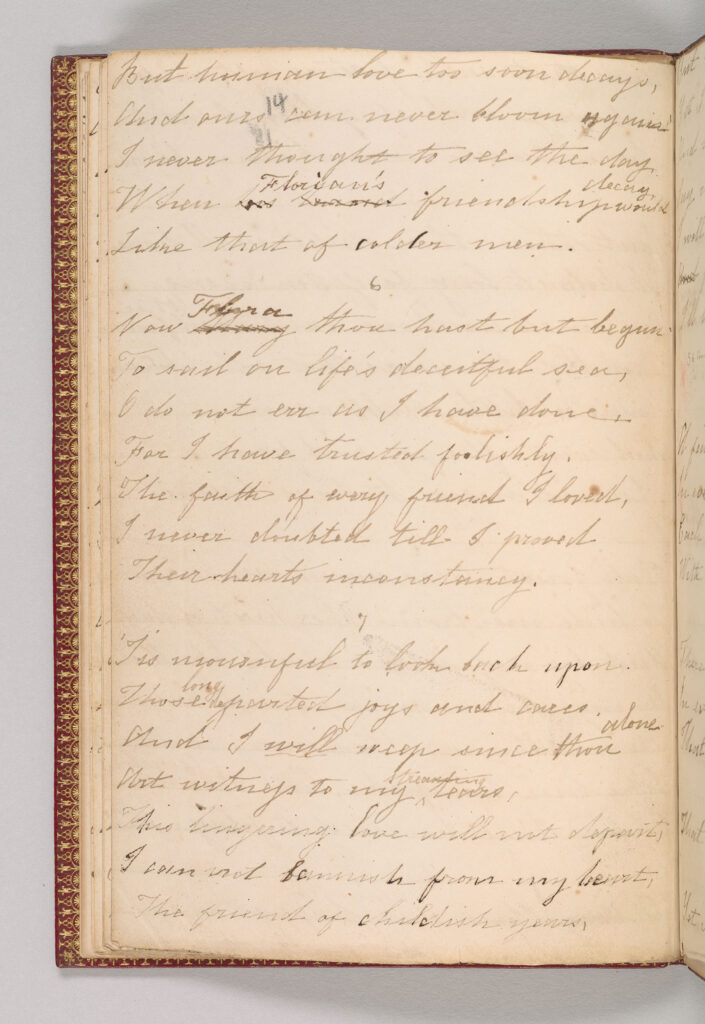

Despite the Bradford subterfuge, Anne, Emily, Charlotte and Ellen soon worked out who their anonymous sender was, and they wrote him a collective poem in return:

“We cannot write or talk like you;

We’re plain folks every one;

You’ve played a clever trick on us,

We thank you for the fun.

Believe us frankly when we say

(Our words though blunt are true).

At home, abroad, by night or day,

We all wish well to you.”

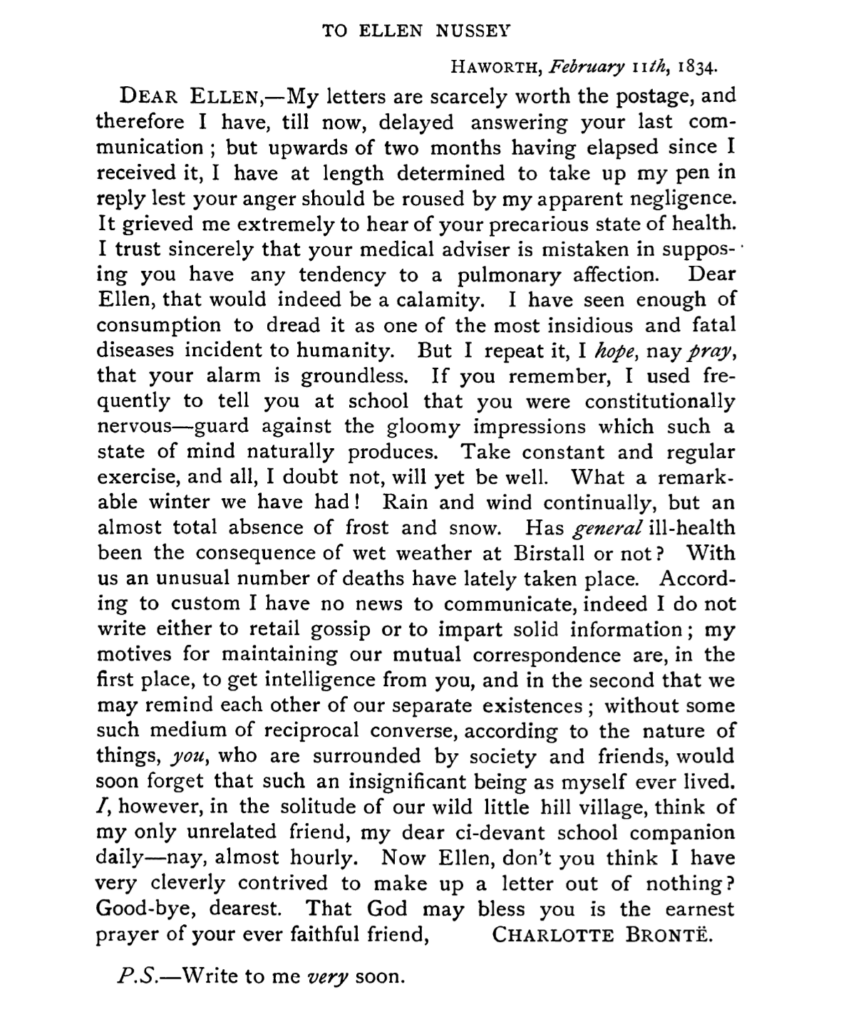

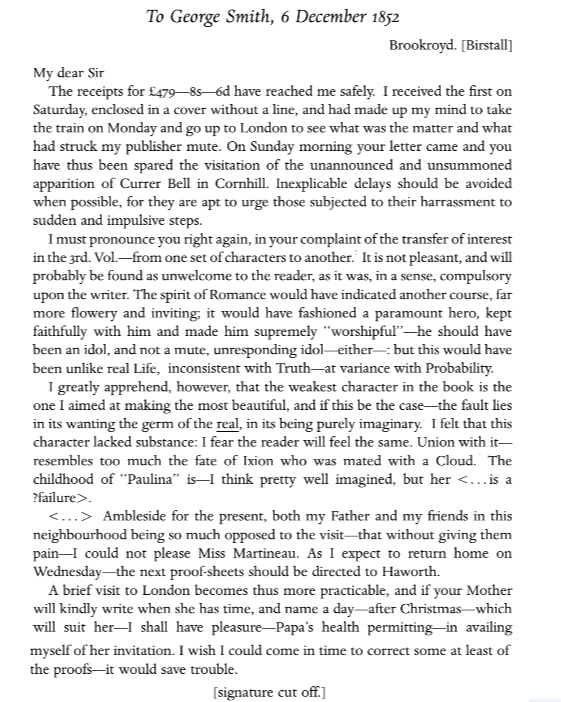

Were the sisters annoyed at being made fun of, or did they see it as an act of kindliness? I believe the latter, but either way we can easily imagine how delighted they must have been when their cards first arrived. These were young women who loved the romance of novels by Walter Scott and the poetry of Byron, and had created their own lands of Angria and Gondal full of the intrigues and mysteries of love, so this romantic gesture must have set their hearts a-flutter, if only for a moment or two. Charlotte in a letter to Ellen dated 17th March 1840 (her father’s birthday, a fact she fails to mention in her letter – but then Charlotte was never very good at remembering birthdays) told of how well received the cards had been, and what an impression they and their sender had made:

‘Walk up to Gomersal and tell her [Martha Taylor] forthwith every individual occurrence you can recollect, including Valentines, “Fair Ellen, Fair Ellen” – “Away Fond Love”, “Soul Divine” and all – likewise if you please the painting of Miss Celia Amelia Weightman’s portrait [Celia Amelia was Charlotte’s pet name for William] and that young lady’s frequent and agreeable visits.”

In February 1841, William Weightman once more sent Charlotte, Emily and Anne Brontë a Valentine’s day card, but this is how Charlotte viewed it now as revealed in another letter to Ellen:

“I knew better how to treat it than I did those we received a year ago. I am up to the dodges and artifices of his Lordship’s character, he knows I know him… for all the tricks, wiles and insincerities of love the gentleman has not his match for 20 miles round.”

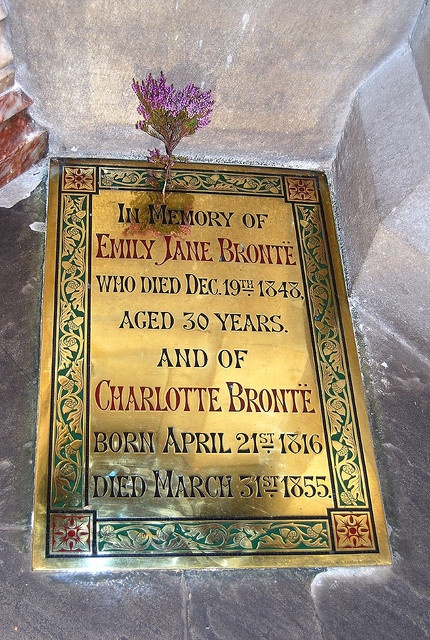

Charlotte had Weightman’s character correct the first time round. His kindness would eventually be his undoing as his passion for visiting sick parishioners led to his early demise from cholera just two years after sending the Brontës their first ever Valentine’s Day cards.

If he had lived longer he may well have sent cards annually to Anne Brontë, for I like to think that they were an ideal match for each other. After all, it would not have been unusual for a young cleric to seek a wife among the daughters of a more senior clergyman, and affection at least certainly grew between them, until we hear of Charlotte complaining that Weightman spends his time in church sighing and gazing at Anne.

It was not to be, alas, but at least the sisters had that thrilling 14th of February in 1840 to remember. I hope that you have a very happy day, whether you’re with the love of your life, looking for that special person, or spending the day on your own with a good book. Please come back this Sunday for a completely new Brontë blog post.