Perhaps one reason for the great power and imagination in the Brontë writing is their family background. They grew up in the Pennine moorlands of Yorkshire but their parents were from Cornwall and Ireland, all areas rich in folklore and famed for their storytelling. The Brontës grew up listening to tales of Cornwall from Aunt Branwell and tales of Ireland from their father, and years later hints of these fantastic tales found their way into their work. In today’s post we’re going to look at an Irish tale which was particularly relevant to the Brontës, and to an Irish cousin of theirs who also lived in Yorkshire and shed further light on it.

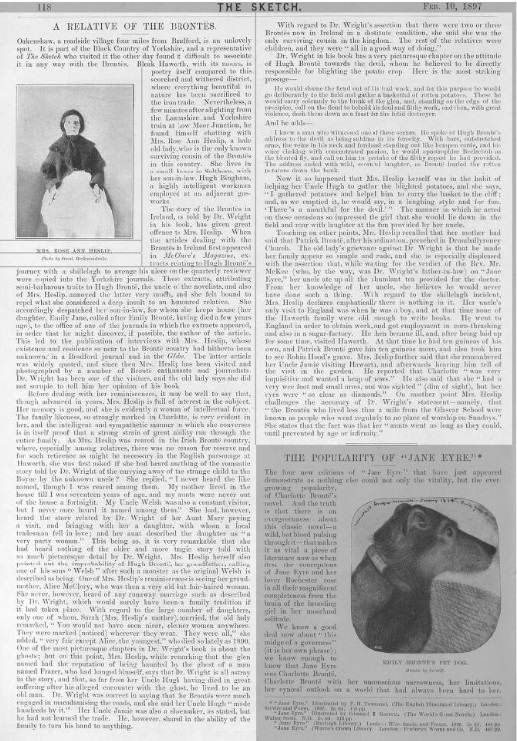

Patrick Brontë was a fascinating and complex, yet inherently kind, man, and his character and life fascinated people as much in the 19th century as it does in the 21st century. In 1893, a Brontë scholar from Ireland, but based in Yorkshire, named Dr. William Wright wrote The Brontës In Ireland which gave a history of our favourite family’s Irish roots; it’s a fascinating book to read and based upon testimony that Wright received while interviewing people in Ireland. Among his claims we find the story of Welsh Brunty, the Brontë ancestor who has more than a hint of Heathcliff about him:

‘On one of his return journeys from Liverpool a strange child was found in a bundle in the hold of the vessel. It was very young, very black, very dirty, and almost without clothing of any kind. No one on board knew whence it had come, and no one seemed to care what became of it. There was no doctor in the ship, and no woman except Mrs. Brontë, who had accompanied her husband to Liverpool. The child was thrown on the deck. Some one said, “Toss it overboard”; but no one would touch it, and its cries were distressing. From sheer pity Mrs. Brontë was obliged to succour the abandoned infant… When the little foundling was carried up out of the hold of the vessel, it was supposed to be a Welsh child on account of its colour. It might doubtless have laid claim to a more Oriental descent, but when it became a member of the Brontë family they called it “Welsh”.’

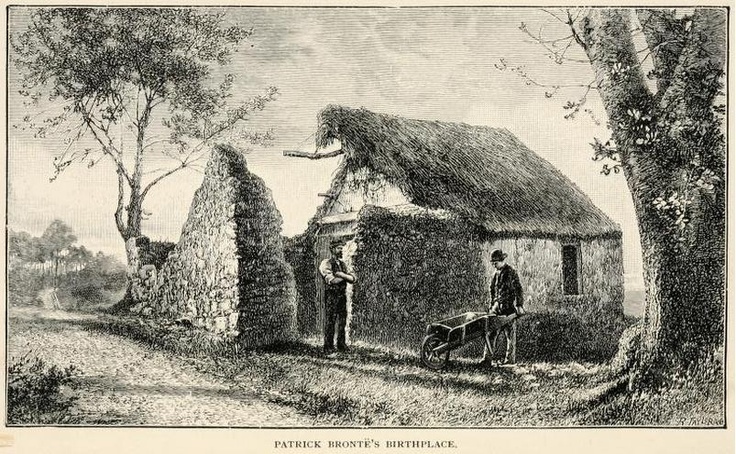

As an adult Welsh supposedly eloped from his new family and married his master’s daughter Mary. He later adopted his brother-in-law’s son Hugh and wreaked havoc upon the family as a whole. This Hugh Brunty, or possibly Prunty, was the father of Patrick. Amidst other exciting claims in the book we read that Hugh himself eloped and married a Catholic girl called Alice McClory, a highly controversial move as Hugh was a Protestant and religious divisions carried much weight at the time.

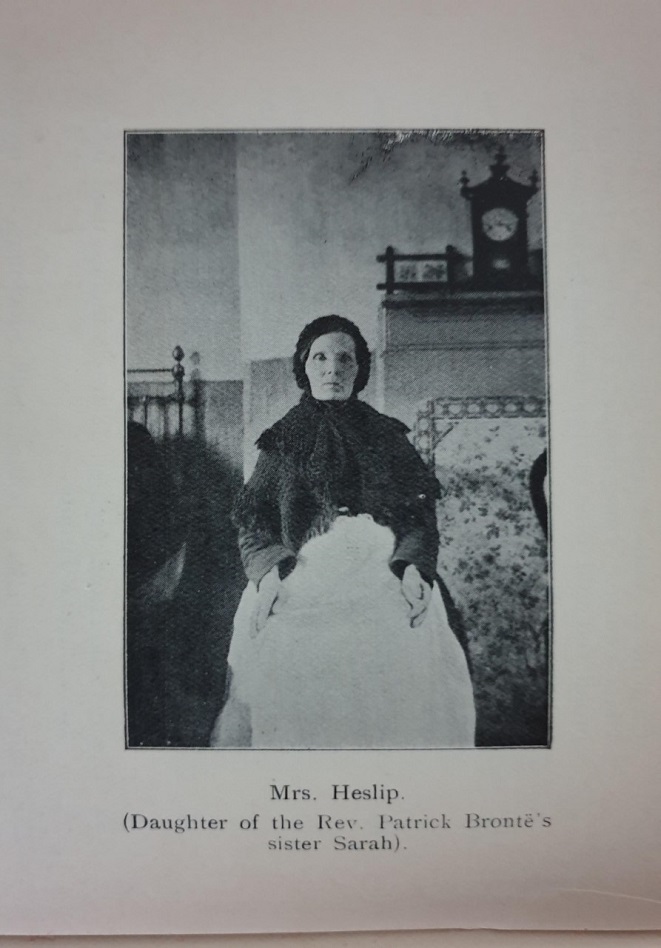

We further discover that Hugh and Alice raise a family of ten children in difficult circumstances, but that Hugh was an eccentric man who threatened people with shillelaghs and that his son also called Hugh furiously threw rotten potatoes into a glen while shouting oaths against the devil. Wright’s book is great fun but much of it cannot be taken at face value, especially as much of it was challenged by someone who knew the true character of the Irish Brontës: Rose Anne Heslip, neice of Patrick Brontë and cousin to Charlotte, Emily, Anne, Branwell, Maria and Elizabeth.

Rose Anne Heslip was born in Ireland the daughter of Patrick’s sister Sarah. At some unknown point in the mid-nineteenth century she married an Englishman named David Heslip and in 1856 came to live in Heckmondwike and then Oakenshaw in Yorkshire, just 12 miles from Haworth.

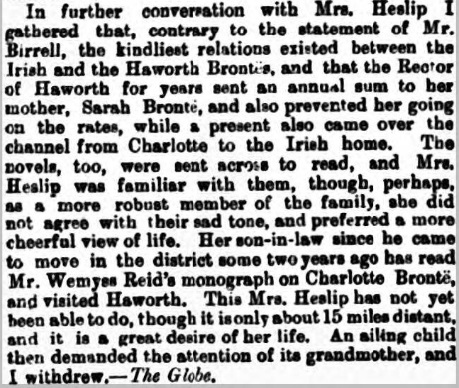

Rose Anne lived in relative obscurity in Yorkshire until the publication of Wright’s book when it was found that an Irish Brontë was still alive and living in Brontë country itself. She gave a number of interviews to newspapers local and national, and she was very keen to point out deficiencies and falsehoods in Wright’s book.

On the subject of Welsh Brontë, she denied utterly the story of his having been a Liverpool foundling:

‘I never heard the like named, though I was reared among them. My mother lived in the house till I was 17 years of age, and my aunts were never out of the house a fortnight. My Uncle Welsh was also a constant visitor, but I never once heard it named among them.’

This Uncle Welsh was brother to Patrick, and Rose Anne sagaciously asks why Hugh would have named a son Welsh if the original Welsh Brunty had treated him as badly as The Brontes In Ireland makes out? Rose Anne also dismisses Wright’s assertion that Patrick’s brother Hugh Brunty died of fright after seeing the ghost of a hanged man named Frazer, and claims that he was wealthier than is portrayed:

‘Dr. Wright is all astray in the story, and that, so far from her Uncle Hugh having died in great suffering after the alleged encounter with the ghost, he lived to be an old man. Dr. Wright was correct in saying that the Brontës were much involved in macademising [tarmacking] the roads, and she said her Uncle Hugh “made hundreds from it”’.

Rose Anne was also angry at the potato throwing story, stating that she had been present on many such occasions and her Uncle Hugh threw the potatoes as a joke that always left his niece rolling on the floor with laughter, and in her interviews she always steadfastly denied the story of the inter-faith elopement between her grandfather and grandmother.

A journalist from the Bradford Daily Telegraph notes that Rose Anne Heslip has a strong facial resemblance to her cousin Charlotte Brontë, but sadly the similarities don’t end there. We learn that Rose Anne had a daughter whom she named Emily after her cousin, but that Emily Heslip died of consumption aged 33, after which Mrs Heslip took in her son-in-law and her grandchildren to live with her. Unfortunately Rose Anne had a sad end herself. In 1904, by which time she must have been in her 70s or 80s, Rose Anne was sent by her son-in-law to Clayton Workshouse as he couldn’t handle her ‘eccentricities’, and it’s also reported that Rose Anne, despite her age, has twice escaped from the workhouse.

There is also a fascinating portrait of Charlotte Brontë given to Rose Anne by her Uncle Jamie after he made a visit to Haworth, but that will appear in next week’s post. The coming week marks the anniversary of the death of Emily Brontë, a time to remember her genius as a writer and kindness as a human, but we could all do with happier tidings at this time of year, and in this particular year. Next week then I will bring you a special pre-Christmas post based upon first-person descriptions of the Brontes from people who actually met and knew them. I guarantee there will be some that you won’t have read before, and some are very enlightening.

Rose Anne Heslip defended her family to the hilt, just as her cousins the Brontës would have done. Family and loved ones are so important as Christmas looms ever closer, so I wish you and yours a very happy week and I will see you here next Sunday for a very special Brontë blog post.

Another fascinating read. Look forward to next weeks!

Thank you Nick. Did you know that Rose Anne Heslip is buried at Whitechapel Church in Cleckheaton? This is not far from the wonderful Red House where Mary Taylor, Charlotte’s friend, lived.

Viewing the Brontës’ lives opens a window on the past. Thank you for this contribution to our lives – in a Canadian winter.

Great post this week. I love these peripheral stories as they are very difficult to research.

(:thumbs-up:)

Why would Dr. Wright spread these lies? What for?

Can’t wait for next week’s post!

Thank you for these precious Sunday Brontë moments!

Have a lovely week!

I am very pleased that we are hearing much more about the extended Bronte and Branwell families. I am currently reading Melissa Hardie’s deeply researched book, ‘Bronte Territories: Cornwall and the Unexplored Maternal Legacy 1760-1860’

It offers fascinating insight into the Branwell and Carne families and highlights the Cornish influences on the Bronte children via their mother and Aunt Branwell. This is an area of study that is only just being seriously researched and alters our perspectives on the ideas and stories that influenced the Bronte girls. Keep up the good work Nick and a Happy and safe Christmas to everyone.

Sorry this is a bit late – I only discovered your blog last week. I couldn’t help thinking that it was a bit harsh for Rose Anne to be put in the workhouse by her son-in-law after she had given him and his children a home. Still, to be fair, maybe she had advanced dementia and was very difficult to look after.