History is an endlessly fascinating subject, not only when it deals with Kings and Queens, great houses and great battles, but when it deals with ‘ordinary people’ as well. I put ordinary in quotation marks, because none of us are ordinary really are we? On the face of it, the Brontë siblings were ordinary people too, but of course they did extraordinary things.

The wonderful television series ‘A House Through Time’ with historian David Olusoga recently came to an end, and it showed the amazing secrets that can lie within an on the surface insubstantial home. The Brontës themselves took a keen interest in news stories from their area, and the lives of the people around them. Even Emily Brontë, always painfully shy and increasingly reclusive, knew the people of her village, as Charlotte Brontë recalled:

‘My sister’s disposition was not naturally gregarious; circumstances favoured and fostered her tendency to seclusion; except to go to church or take a walk on the hills, she rarely crossed the threshold of home. Though her feeling for the people round was benevolent, intercourse with them she never sought; nor, with very few exceptions, ever experienced. And yet she knew them.’

The Brontë family were avid readers of news local and national, and in 1847 one particular story is sure to have caught their attention – a savage triple murder in Mirfield, the town where Charlotte, Emily and Anne Brontë had attended Roe Head school, and where Anne had served as governess to the Ingham family of Blake Hall.

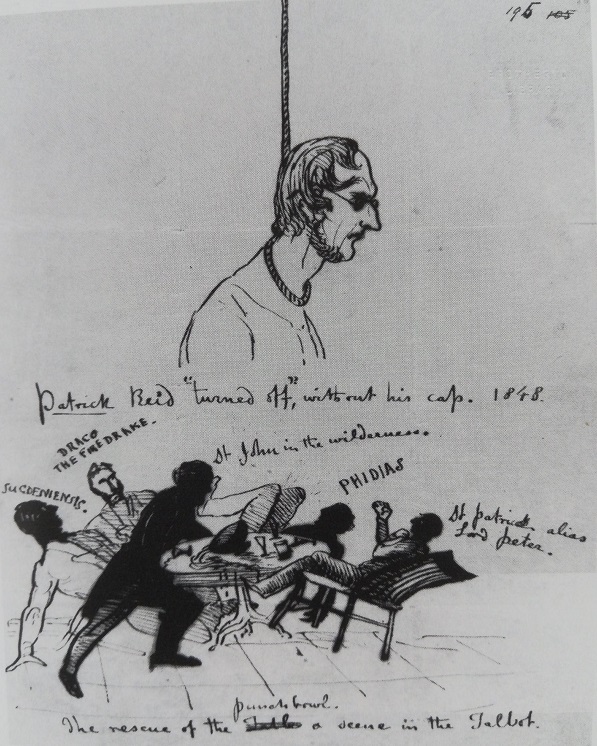

It was a case that shocked, or possibly enraptured, the whole of Yorkshire – and we can be certain that Branwell Brontë took a keen interest in it because of his drawing of ‘Patrick Reid turned off, without his cap’. This ‘turning off’ was the public execution of the murderer Patrick Reid, but who was he and who were his victims? It’s a terrible tale with a bizarre twist.

The fateful event took place on 12th May 1847 at Water Royd House (that’s it at the top of the picture, it’s no longer extant although it was during the time I myself worked in the village) in a rural area of Mirfield away from other habitations. It was owned by James Wraith, a 77 year old man who lived there with his 65 year old wife Ann. Wraith had previously served as steward to Joseph Ingham of Mirfield’s Blake Hall. Ingham had also employed Anne Brontë at the hall as well of course, and was later portrayed as the cruel Mr Bloomfield in ‘Agnes Grey‘. It’s likely then that Anne would have known the ill fated Wraiths.

They were a wealthy couple in their own right, thanks to a string of property they owned, and they had their own servant girl Caroline Ellis. She had become embroiled in an argument with a local knife grinder – Patrick Reid. Reid accused her of stealing a tea caddy from him, whether this was true or the circumstances surrounding it we’ll never know, and on the 12th May he created a scene at Water Royd House demanding that Caroline make repairs for her theft.

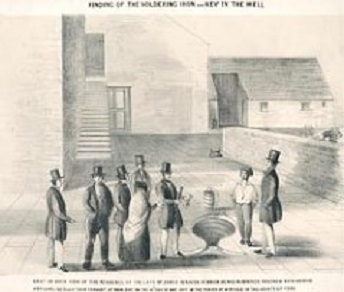

James Wraith ordered Reid to leave the house, but he vowed to return and wreak revenge. He then called upon an Irish tinker called Kilty and borrowed a soldering iron, after which he returned to Water Royd House and struck Caroline Ellis on the head. He was then confronted by James Wraith and then Ann Wraith, and he dealt them all the same blow, leaving them fatally wounded. To complete his evil work, Reid rifled their pockets and finally cut the throats of all three individuals. Caroline Ellis had been due to be married just four days later.

Reid was soon under suspicion as his quarrel with the Water Royd residents was well known. He was placed under arrest and committed to trial at the York assizes in July 1847. The trials gained huge press attention, but they were rather farcical as contradictory evidence was brought, and Reid was cleared of the murder of James Wraith. He was later, however, found guilty of the murders of the two women, and in December he was sentenced to hang.

The day of execution was set for 8th January 1848, a day that we know was terribly cold – and yet that did not diminish the huge crowds that gathered in York’s Knavesmire to see the triple killer’s execution. The Leeds Mercury reported that it was the greatest gathering ever assembled there to see a public hanging:

‘Probably on no occasion has an execution, within our recollection, drawn together so vast a concourse of spectators. Besides bringing together a very large proportion of the inhabitants of York and its more immediate vicinity, many towns in the West Yorkshire Riding added their thousands to swell the general throng From Halifax, Bradford, Wakefield, Barnsley, Leeds, Huddersfield, Dewsbury, Mirfield, Pontefract, and indeed from every other place, great and small, contributions of inhabitants to the vast multitude took place. Some idea of the proportion which Leeds bore, may be formed from the fact that by the 7.20 a.m. train alone there were conveyed to York more than 1,000 extra passengers. All the available carriages were put into use, and still hundreds were left behind, at that time, to be conveyed by a subsequent train. This, however, gives but a very imperfect estimate of the number of persons that went from Leeds to York, as it is exclusive to pedestrians, many of whom even as early as the previous night, left this little town to visit the scene of the execution. It may be truly said of this occasion, that the soul-depressing exhibition of a criminal on the scaffold, drew more persons early from their rest on the coldest morning of the winter, than the most transcendent exhibition of virtue could probably have by a accomplished with all the charms and temptations of one of summer’s most attractive days.’

The spectacle didn’t stop there. After his most public death, a showman named Andrew Purchase purchased the clothes Reid was wearing and the rope that was used to hang him, and he took them while the body was still warm. Purchase then had an effigy of Reid made, dressed it in the dead man’s clothes, and restaged his execution at shows across the north of England.

Did Branwell Brontë attend Patrick Reid’s execution? We don’t know, but we do know of course that the person depicted in his picture isn’t Reid at all, but the artist himself being hanged. It was a sign of Branwell’s inner turmoil at this time, and below the self portrait is the scene of a drunken brawl. The history of ‘ordinary people’ can be a fascinating one indeed, but it’s also frequently a tragic one.